A previously unknown cache of 40 handwritten Naguib Mahfouz short stories were recently unearthed by the journalist and literary critic Mohamed Shoair, who found them in a box of papers given to him by Mahfouz’s daughter Umm Kalthoum.

Many had been published during Mahfouz’s lifetime (1911-2007), but what made this a sensational discovery is that 18 of them have never been collected.

Under the title Stars Whisper, therefore – this is the title of one of the stories, chosen by Umm Kalthoum – a new book is now being published by Dar Al-Saqi, who are launching them on 11 December, Mahfouz’s 107th birthday.

Translated by Roger Allen – who also translated several Mahfouz books: Mirrors (1999), Autumn Quail (1986), Karnak Café (2008), Khan al-Khalili (2009), and The Final Hour (2010) – they will appear in English next autumn.

Cover of the book titled Stars Whisper (Hams Al-Nujoum)

Shoair had been researching for Sons of Gebelawi: Biography of the Forbidden Novel (Cairo: Al-Ain, 2018), the first part of a biographical trilogy about the late Nobel laureate.

Much has been written on Mahfouz, Shoair concedes, but the man is “an iceberg” and none of what’s available trally goes beyond its tip: “It’s an honour to be one of those who explore his work in depth.

Critics generally focus on his better-known work, but all that he did in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, remains untouched. What is more, however, Mahfouz was a private person who kept his personal life separate from his writing, he used to say ‘I only exist in my text’, but what I’m trying to do is look for him outside that text, to see how his life informed his writing.

This is an attempt to reread and rediscover his work.” To see Mahfouz as a historian of Egypt – The Cairo Trilogy accurately documenting ideological, social, political and artistic life in 1919-1952, for example – would be reducing great literature to anthropological source material.

More pertinent, Shoair believes, is the technique, the language and the space between reality and imagination.

Using that biographical approach, Forbidden Novel focuses on Mahfouz’s most controversial work, Shoair explains:“I started by searching for the manuscript and though I never found it I did find other manuscripts and important documents, including a file containing 40 stories with the words ‘An attempt. Length, type and treatment to be decided’ scratched out and replaced with ‘Stories to be published, 1993-1994’.”

This meant in book form. But, because Mahfouz was busy first with the publication of his Echoes of an Autobiography (1994) and then with the October 1994 attempt on his life by religious extremists, no book materialised immediately.

Two years later Al-Ahram’s Nisf Al-Donia magazine started publishing some stories, tagged “The latest from the Nobel laureate”. One story, “The Arrow”, appears in a General Egyptian Book Organisation collection of stories from 1996 as the latest by Mahfouz.

All except for 18 – one of which, “The Buckthorn in the Old Fort”, was never published at all – are included in Mahfouz’s last two collections, The Last Decision (1996) and Echo of Forgetfulness (1999).

The stories had been completed before Mahfouz was attacked with a knife, but he was hesitant to publish them in book form, Shoair believes, because they were in a new style, unknown in Arabic literature, and critics had not noticed those of them that appeared in the press.

Some commentators have argued that, since he would’ve collected them if he’d wanted them to be published, Stars Whisper may be a violation of the late writer’s autonomy.

But Shoair feels that, since there is no doubt that Mahfouz was happy with their quality, there is no reason to think he would’ve been averse to seeing them in book form. “Besides, if posthumous publication always respected the writer’s wishes we would have none of Kafka’s works – can you imagine! – that’s true of many other writers, too.”

The stories in Stars Whisper are set in the alleys of grassroots Cairo – Mahfouz’s favourite mythological world – and populated by lunatics, astrologers, saints, runaways – from blood feuds, star-crossed loves, overbearing circumstances – and imams as well as fituwwas (or chivalrous strongmen who protect the neighbours).

These characters occupy the space between the basements where the poorest live and the haunted Old Fort, the highest point on the horizon.

Their evocative names bear – and eventually bare – their destinies. Like Sons of Gebelawi, these stories revolve around the passage of time and Mahfouz’s greatest faith is as always in those characters “who can emanate light in the darkness, who pick out the melody within the noise,” as shoair puts it – “the artists”.

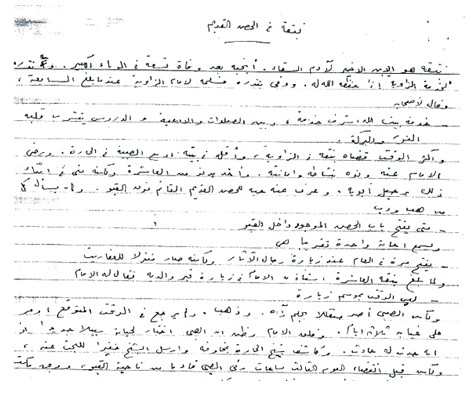

Manuscript from the lost stories of Mahfouz

As a literary institution Mahfouz’s opus should be as complete as possible. The stories fit seamlessly into the writer’s legacy, they belong with Fountain and Tomb (1975) and Echo of Forgetfulness (1999): “They follow the same childhood thread but with more symbolism and maybe greater wisdom.”

Even the title, Stars Whisper (Hams Al-Nujoum), echoes that of Mahfouz’s first short story collection, Madness Whispers (Hams Al-Junoun), published in 1938.

“Maybe this journey from madness to the stars,” Shoair says, “actually summarises Mahfouz’s life and literature.” Be that as it may, the new book definitely brings the author’s career full circle.

The book will feature reproductions of the manuscripts which demonstrate Mahfouz’s editing process, especially evident in this case since his handwriting was greatly affected by the knife attack, which occurred after they were written and before they were published. “Mahfouz spent years editing the stories until he was satisfied – additional proof that he wouldn’t have objected to publication.”

Shoair’s next book will be called Naguib Mahfouz’s Manuscripts: “Mahfouz used to call himself the king of shredding because of how often he used a shredder.

He did not keep manuscripts of his work, and that is why even the parts that were cut from the published versions of Karnak Café (1974) and Love in the Rain (1973) cannot be found.

But some papers did survive, mostly by accident, and these will be my focus.” The book will compare manuscripts of Miramar (1978), The Dreams (2004) and Echoes of an Autobiography (1994) to the published versions, and explore an unpublished early novel that was a rehearsal for the Trilogy as well as diaries from various periods:“I have 14 manuscripts to date, but I’m still looking and willing to expand the book.They reveal the secrets of Mahfouz’s creative process, his relationship with his texts and characters and his writing rituals. I am almost done, with only revision and the appendices remaining, but these are very difficult tasks in themselves. I expect it will be published in early 2019.”

Shoair’s journey into Mahfouz’s life and work has been a joy, he says, but also a dilemma because it is like a journey through the Great Sand Sea: “Once you pose one question ten more questions come up. But maybe Mahfouz is the journey of my life. I doubt if it will add to Arabic literature as such, my enjoyment and the reader’s are satisfying enough.”

*A version of this article appears in print in the 15 November, 2018 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: Buried treasure

Short link: