“The president of the assembly, Al-Sayeda Zeinab, listens attentively to the lamentations of all the creatures, even the lament of trees lashed by the wind.”

From The Book of Illuminations by Egyptian novelist and writer Gamal Al-Ghitani (1945-2015)

Her mausoleum, adorned in a bridal veil, is bathed in a particular light, and together with the scent of incense that fills the place, this sets the scene for spiritual reflection.

Al-Sayeda Zeinab, the granddaughter of the Prophet Mohamed, who was born to his beloved daughter Fatma and his cousin Imam Ali Ibn Abi Taleb, is the object of passion of many Muslims around the world.

It is the holy month of Ramadan, a time when many devoted Muslims, and particularly Sufis, choose to visit the mosques of the prophet’s family (ahl al-beit), seeking their blessings, praying, and reciting the Quran.

Egypt has a large number of saintly shrines. A study entitled Maraqid [Shrines] Ahl Al-Beit in Cairo by professor of geography at the Faculty of Arts at Damanhour University Abdel-Azim Ahmed Abdel-Azim, shows that Cairo alone hosts some 34 shrines related to the ahl al-beit, while mausoleums of the saints may amount to 1,000 nationwide.

Controversy surrounding who is actually buried in these mausoleums notwithstanding, there is almost a consensus that more attention should be granted to the mosques housing those shrines, particularly the smaller ones that may be suffering from neglect despite their historical and religious significance.

Al-Sayeda Nafisa Mosque

Al-Sayeda Zeinab’s neo-Mameluke Mosque, which dates back to the Fatimid period and houses her shrine, stands in majesty in a populous square in Cairo that also carries her name and receives hundreds of passionate worshippers every day.

Away from the hassle and bustle of the populous area around it, the interior of the mosque exudes a sense of historical and spiritual grandeur.

Those who visit her shrine are not just the afflicted seeking her blessing, or members of Sufi orders who consider visiting the shrines of saints and mausoleums an important part of self-purification, but also those who feel a passion to remain in the company of the “president of the assembly”, as many Sufis like to dub Al-Sayeda Zeinab.

The “assembly” here means the prophet’s descendants and saints who have a special status in the hearts of Muslims and whose shrines are believed to have particular blessings for those seeking an answer to their prayers.

Al-Sayeda Zeinab, however, is more popularly known as the mother of those who suffer from many calamities. She bravely participated in the Battle of Karbala in 61 AH (680 CE), one of the dramatic battles that ultimately divided the Muslim world into Sunni and Shia sects, and where she saw her brother Al-Hussein beheaded and she was taken a prisoner of war.

There has long been controversy, however, as to who is actually buried in the shrines of the ahl al-beit in Cairo. Al-Sayeda Zeinab, like Al-Hussein, has another mausoleum in Damascus, but many Egyptian historians insist she was nevertheless buried in Egypt and that the head of her brother Al-Hussein was also buried in another mausoleum in a nearby district that also carries his name.

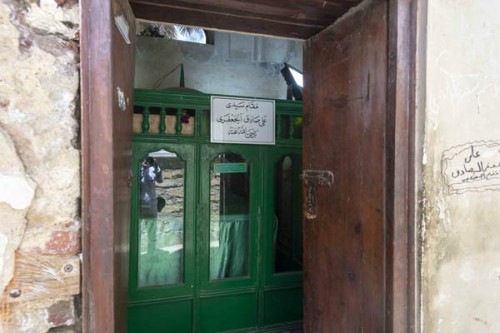

Ibn Sirin shrine

Sanctuary In Egypt

According to many Egyptian accounts, Al-Sayeda Zeinab came to Egypt after having been taken as a prisoner of war to the court of the caliph of Damascus, Yazid Ibn Muawiya, after the Battle of Karbala.

In the Egyptian accounts, Zeinab chose to spend the last years of her life in Egypt because it was a country known for its hospitality to prophets.

“The first information about the mausoleum dates back to the 16th century, and some say it is based on the dreams and visions of Sufis to whom Zeinab appeared, revealing her burial place,” historian Saleh Lamei said in an article published in Al-Ahram Weekly in 2003.

“According to the concurrent Shia version, Zeinab died in Damascus, a city in which she lived after the tragic events which marked her life. Attempts to demonstrate the presence of the saint’s body in Cairo or Damascus have succeeded one after another from mediaeval times to our own day.”

Al-Sayeda Atika shrine

Professor of Islamic history at Al-Azhar University in Cairo Abdel-Maqsoud Basha insists that Al-Sayeda Zeinab was buried in Egypt, which he said was the destination of many of the prophet’s family and companions.

Motivated by his deep passion for the ahl al-beit, 69-year-old Basha has spent many of his seven decades travelling around the globe in attempts to find the truth about many mausoleums by exploring ancient maps and old manuscripts. These long years of research have left him unabashed in the face of critics.

For him, there is no doubt that Egypt has “been blessed to house the shrines of many members of the prophet’s family, and it is thanks to their blessed bodies that Egypt has survived many calamities,” he said.

Basha met with many historians and Shia scholars in Syria and Iraq and even visited the mausoleums of Al-Sayeda Zeinab in Damascus and Al-Hussein in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

“There I was told that Al-Sayeda Zeinab’s shrine was built in commemoration of the place where she stayed before heading to Egypt, where she ultimately died and was buried,” he told the Weekly.

When Al-Sayeda Zeinab first arrived in Egypt in 61 AH (680-681 CE), she was heartily welcomed by all Egyptians and by the Umayyad wali (governor) of Egypt Maslama Ibn Makhlid Al-Ansari.

She was said to have settled in Fustat in Old Cairo near Al-Ansari’s residence but passed away shortly after a brief stay of less than a year in 62 AH.

She was reportedly buried in the same place she had lived in for about 11 months, and a mausoleum was built in its present location while the mosque was built and renovated over the course of centuries.

An ardent lover of the ahl al-beit, Basha also visited the mausoleums of Al-Sayeda Sukayna, the daughter of the prophet’s grandson Al-Hassan, in Damascus and prayed in the Umayyad Mosque where Al-Hussein is said to have been buried close to the mausoleum of the Prophet Yehia.

“I was told that the mausoleum of Al-Hussein in Damascus marked the place where the casket carrying the head of Al-Hussein, which was brought to Asqalan [in Palestine] by his sister Zeinab after the Battle of Karbala, was treasured,” Basha recounted.

“It remained there for years until the Fatimid caliph ordered its transfer to Egypt in a special ceremony for fear that the European Crusaders would trespass on it during their war on the east. A Fatimid minister then brought the head from Asqalan to Cairo, carrying it barefooted in awe of the blessed head of the prophet’s beloved grandson.”

A debate among scholars over whether Al-Hussein’s head was actually buried in Egypt ended up with a decision to dig up his tomb. “The diggers found a wooden casket and a strong aroma of incense came out of it,” Basha said in an emotionally charged tone.

“They went on to open the casket, only to find another casket with an unmistakably strong smell of incense that filled the whole place. Only then did scholars feel assured that it was Al-Hussein’s head inside and decided not to dig any further.”

Basha could hardly hold back his tears as he delved deeper into accounts of how Egypt hosted the prophet’s family. “When the great granddaughter of the prophet’s grandson Al-Hassan, Al-Sayeda Nafisa, died, her husband insisted on burying her beside her grandfather in what is now Saudi Arabia, despite the fact that Egyptians had heartily pleaded for her to be buried in Egypt, even offering gold in return,” Basha recounted.

The mausoleum of Al-Sayeda Sukayna

Suddenly, however, Al-Sayeda Nafisa’s husband changed his mind and was seen departing without his beloved wife’s body or the money. “When asked why he had changed his mind, he said he had seen the prophet in a dream telling him to let his wife be buried in Egypt,” Basha said.

He said he had stumbled over old manuscripts in Al-Azhar indicating a particular corner of Al-Sayeda Nafisa’s shrine where “doaa [prayers] are particularly answered by God.”

For Basha, most of the Cairo shrines of the prophet’s family and companions have been verified. “Those who try to cast doubt are mainly Salafis who argue against building shrines or praying in mosques housing them,” he continued.

“But to them I say, then how do we pray at the tomb of the Prophet Ismail just beside the Kaaba in Mecca?”

Al-Ashraf Street

I started my visit to the mausoleum of Al-Sayeda Nafisa, the great-granddaughter of Al-Hassan, one of the Prophet Mohamed’s two grandsons to his daughter Fatma and his cousin Ali, located in the Al-Khalifa district in the cemetery area in Islamic Cairo where a wealth of mausoleums is largely hidden.

Inside the mausoleum, a sense of peace reigns, and visitors belonging to different ages and social classes could be seen engaged in prayers. A woman in a wheelchair was rushed to the mausoleum, and the moment she reached it she closed her eyes in silence and tears rushed down her cheeks.

It was in this secluded area that Al-Sayeda Nafisa chose to lead a life of deep piety. Historians say that she immigrated to Egypt, where she stayed for years educating Egyptians about their religion and helping the poor and afflicted.

It is said that when she felt death approaching, she decided to dig a grave in her secluded abode and spent many nights praying and reciting the Quran inside it.

A shrine to her memory was constructed in the Ayoubid period, and it was later embellished and rebuilt many times, first by the Fatimid caliphs and most recently by the Ministry of Religious Endowments, according to Lamei’s chronicle.

“People come to visit Al-Sayeda Nafisa all year round, and this particular time of the year of course,” said one of the guards. “Visitors usually start their journey here. Then they head to the mausoleums in Al-Ashraf Street and then take a bus to Al-Sayeda Zeinab and Sidi Zein Al-Abidine, the son of Al-Hussein.”

The mausoleum of Ali Al-Gaafari

Al-Ashraf Street extends from Al-Sayeda Nafisa Square in the south to the intersection with Al-Saliba Street in the north, and from Darb Al-Hosr to the tomb of Al-Sayeda Ruqaya.

A plaque carrying the street’s name hangs on the right, while on the other side of the narrow alleyway a map ushering visitors to a wealth of historic monuments dating from the Fatimid, Ayoubid, Mameluke and Ottoman eras of Egypt’s history hangs on an ancient wall.

The area, hardly known to many despite its wealth of saintly inhabitants and historic significance, is like an open-air museum. The treasure, however, dwells in narrow streets that also host debris, stray dogs, tok-toks, and workshops, and in some parts overflowing groundwater.

Al-Ashraf Street was once the path of ceremonial processions led by the Fatimid caliphs to the southern sections of the city. Among the historic buildings are a number of mausoleums that belong to historical characters like the famous Egyptian Sultana Shagaret Al-Dor, whose cunning helped defend Egypt from the Crusaders following the death of her husband Saleh Nijmeddin.

Just down the road is the mausoleum of the Sultan Al-Ashram Ibn Qalawoun, renowned for expelling the last of the Crusaders from the Levant.

According to Lamei’s chronicle, “Al-Ashraf is the most recent name given to the street on which lies the mausoleum of Sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil, the son and successor of Sultan Al- Mansour Qalawoun.”

According to Dreams that Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of Imagination by scholar Amira Mittermaier, although Al-Ashraf looks like many other narrow streets in Cairo, it remains “special” and “for some, it’s one of the most sacred in the entire city.”

“As Sheikh Nabil [one of this study’s main interviewees] likes to point out, practically anywhere in the street one stands on top of hundreds of dead people, since the entire area used to be a cemetery,” Mittermaier wrote. The street also hosts a number of shrines of the ahl al-beit.

“Thus, the name of the street refers to the prophet’s descendants,” Mittermaier wrote.

Al-Sayeda Ruqaya shrine

As I walked down the street, I came across a small green-and-white-striped building, which turned out to be the mausoleum of Abu Bakr Mohamed bin Sirin, known as Ibn Sirin, a pioneer of the science of the interpretation of dreams in Islam.

Imam Ibn Sirin was born in Basra in 33 AH and was known for his piety. Ironically, as Mittermaier describes in her book, unlike other cemeteries, “in Ibn Sirin’s shrine, the presence of the dead contributes to a peaceful and joyous atmosphere.”

I was overwhelmed by a sense of peace and awe on visiting the many small shrines lining Al-Ashraf Street. The small shrines are less popular, are frequented by fewer visitors, and, as Mittermaier put it, “are calmer and more intimate than the larger ones”.

Only a few steps away, I found myself at the entrance of the Mogamaa Al-Awleya, the cemetery hosting many of the prophet’s family, including Al-Sayeda Ruqaya, Al-Sayeda Atika, Sidi Ali Mohamed Al-Gaafari, the third great-grandson to the Prophet Mohamed through Al-Hussein, and Mohamed Al-Anwar, who is said to be the son of Zein Al-Abidine, grandson of Ali through Al-Hussein.

The shrine of Al-Sayeda Ruqaya probably refers to the daughter of Ali Ibn Abi Taleb, the fourth caliph. A plaque at the entrance of the shrine says that “the Fatimid historian Al-Ubayadi recounts that Al-Sayeda Ruqaya came to Al-Hafez Abdel-Maguid Al-Fatimi in a dream and led him to a spot where he found a grave that he marked as hers.”

According to the same plaque, the shrine was established a few years later in 527 AH / 1133 CE by Alam Al-Amiriya, the wife of the Fatimid caliph Al-Amir. It has been renovated several times since then, and its rectangular structure with a central dome is an excellent example of Late Fatimid architecture.

Next to it is the shrine of Al-Sayeda Atika, who is believed to be the aunt of the Prophet Mohamed. Many historians , however, suggest the shrine probably belongs to another Atika, who is said to be the daughter of Zaid, the son of Amr bin Nufayl Al-Kurashi.

She was known for her beauty and poetic talents that haunted her husband Abdallah, the son of Abu Bakr, the prophet’s companion and first caliph. It is said that when Abdallah died in battle, Atika wrote poems mourning him and decided never to remarry.

A map ushering visitors to important sites in Al-Ashraf Street

She changed her mind, however, when Omar Ibn Al-Khattab (the second caliph) insisted she was too young to remain unmarried and decided to marry her himself. After Al-Khattab’s death, Atika was then remarried to the prophet’s companion Al-Zubayr Ibn Al-Awam.

Ali Mohamed Al-Gaafari (d. 824 CE) was the son of Gaafar Al-Sadek, the grandson of Ali Zein Al-Abidine, son of Al-Hussein, son of Imam Ali. Thus, Al-Gaafari is considered to be the third great-grandson of the Prophet Mohamed.

According to Lamei’s chronicle, his shrine was built by the Fatimid caliph Al-Hafez in 1120 CE, and it features a small square structure topped by a ribbed dome.

“Many Egyptians hardly know about this place or anything about who is buried here,” lamented one visitor, a businessman with an MA in Islamic history from Al-Azhar University. “But it’s good to see young people coming to explore it.”

He was referring to a young couple who entered in peace, probably reading the Al-Fatiha from the Quran, and a group of Asian worshippers, probably belonging to the Bahara cult, who were touring the shrines in awe.

Another visitor, a companion of the businessman, nodded in dismay. “I lived in a nearby neighbourhood for decades and knew almost nothing about the shrines. The government should give more attention to this historic and spiritual area and put it on the map,” he said.

I then moved to visit the shrine of another descendant of the prophet through the lineage of Ali, Mohamed Al-Anwar, who is said to be the son of Zein Al-Abedin, grandson of Ali through Al-Hussein. Some sources, however, suggest that the shrine belongs to the uncle of Al-Sayeda Nafisa.

A plaque hanging on a wall in the shrine said that “there is some confusion as to who the shrine commemorates.” It said that “most of the shrines are vision shrines in the sense that they commemorate the appearance of a religious figure to the founder in a vision, not in the presence of an actual grave.”

The small mosque of Al-Sayeda Sukayna lies a few minutes away down Al-Ashraf Street, where a small shrine commemorates the daughter Al-Hussein, the son of Ali. The small mausoleum was built by Abdel-Rahman Katkhouda in 1760, and it has been renovated several times over the course of its history.

At the entrance, a plaque introduces visitors to Al-Sayeda Sukayna, who was originally named Amena, after the prophet’s mother, but was nicknamed Sukayna (serenity) when people found peace and happiness in her company.

Today, visitors to Al-Sayeda Sukayna’s shrine say they have a sense of peace at her mausoleum. Nour Al-Sabah (meaning daylight), an ardent Sufi worshipper who wanted to be nicknamed Nour Al-Sukayna (the light of Sukayna), talked passionately about her spiritual experience and regular visits to the shrine.

The mausoleum of Al-Hussein (photo: Reuters)

“Al-Sayeda Sukayna is my love and my mother,” Al-Sabah said. “It is here that I feel great respite, that I see a light that helps me on my journey to purify my heart and reach a higher spiritual state.”

Both Al-Sabah and the imam of the mosque would shrug at the idea that there is another shrine for Al-Sayeda Sukayna in Damascus.

After all, according to Sufi beliefs “the wali [saints and descendants of the Prophet] are not tied to their graves and are free to come to those who evoke their presence,” the imam explained.

“You visit them out of love for the Prophet; this love will reach them wherever they are,” he explained. Al-Sabah nodded in approval. “They are in the heart, no matter where we go, our deep passion evokes her presence,” she said.

Love Of The Ahl Al-Beit

The love that Muslims have for the Prophet Mohamed and his descendants is an integral part of their faith.

However, according to a study by scholar Valerie J. Hoffman-Ladd, Devotion to the Prophet and His Family in Egyptian Sufism, Sufis consider themselves almost defined by the intensity of their love and devotion for the prophet and his family, calling themselves “those who love the ahl al-beit” as a result.

Whereas Sufism is mainly about the purification of the heart, sincerity of worship, or spiritual development to the level of ihsan (perfection) and the renunciation of worldly pleasures, Hoffman-Ladd shows how “these ends were largely met through practices of devotion to the prophet, his family, and one’s own sheikh.”

“This devotion entails not only practices of shrine visitation, but also doctrines regarding the cosmic significance of the prophet and his family,” Hoffman-Ladd says. One of the book’s Sufi interviewees puts it this way: “the prophet is our intercessor and the one who brings us close to God, and it is through his family that we come close to him, just as the prophet said, ‘Hussein is from me and I am from Hussein. Whoever loves Hussein loves me.’”

“It is love for the family of the prophet that causes us to be purified,” another Sufi interviewee agreed. “This is why we come to the shrines of the family of the prophet. Why else would I leave my comfortable bed and come sleep on the pavement?”

Basha told the Weekly that visiting the ahl al-beit was “almost mandatory for all Muslims”. To prove his point, Basha recited a Quranic verse that is widely interpreted as meaning that the prophet did not ask Muslims for rewards for delivering the message “except the love of those who are near of kin (al-mawadda fil-qurba).”

But although the mausoleums in Cairo could be great attractions for many, there is little or no attention on the part of the government to invest in them.

According to Abdel-Azim’s study, the government has not made any tally of actual or potential visitors, and little to no attention has been given to the surroundings of the mausoleums that should be put on the map.

The study also shows that government attention is usually focused on popular shrines housed in big mosques like Al-Sayeda Zeinab and Al-Hussein, while smaller shrines, including those in Al-Ashraf Street and the cemetery area, remain largely neglected and even largely unknown to the public.

According to Abdel-Azim’s survey, many visitors already come to visit the shrines of the ahl al-beit, particularly Al-Sayeda Zeinab and Al-Hussein.

Those visitors are mainly worshippers coming from countries with a Shia and Sufi Muslim majority, such as Syria, Iran, Pakistan, Yemen, Iraq and Sudan, and also from South Asian countries where the Bahara cult is concentrated.

Some 61 per cent of such visitors come in groups, and unlike among Egyptians their visits are not scheduled at times of the moulids (celebrations of the birth of saints) alone.

Whereas nearly 50 per cent of tourists visiting the shrines come to seek the blessings of the ahl al-beit, there are also tourists who visit the shrines for their cultural and historical significance, according to Abdel-Azim’s study. The study thus recommends investing in the shrines to generate income.

“A presidential committee should be formed with a mandate to preserve the shrines and their surroundings,” Basha said. “The shrines of the ahl al-beit are a major blessing and could be an enormous asset to the country if invested in.”

*A version of this article appears in print in the 30 May, 2019 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: For love of the Prophet Mohamed

Short link: