As the thousands of youth strode defiantly towards Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the lifelong activist felt her work was almost complete.

It was only midday on 25 January 2011, but already throngs of Egyptians had answered the call for protests. Waving the national flag and roaring defiant chants, they demanded the fall of the regime headed by a president who had ruled over them for 30 years.

Writer Ekram Youssef was in one of the first marches to snake through the city. As she stared in wonder at the procession that surrounded her, a smile slowly spread across her face.

“If I die today, I die happy,” Youssef, 58, recalls telling those walking beside her. “My dreams have come true.”

A few hours later, novelist Mahmoud El-Wardany arrived in Tahrir. The still-sprightly 61-year-old clambered over an iron gate and reached a spot that gave him a view over the plaza.

“I could see far, and there were thousands of protesters,” he remembers. “The 18 days of the revolution were the only days I lived. They are the only days in my life that count.”

For Egyptian poet Zein Al-Abadin Fouad, the sight of a sea of demonstrators in Cairo’s landmark square was spellbinding. “I really felt like I saw a beautiful dream and entered it,” says the 72-year-old, four years later.

Not all eyes were on the square; Ahmed Bahaa Shaaban, a publisher and founder of the Egyptian Socialist Party who was among the protesters, found himself looking up at the sky to see what is in Cairo a rare occurrence.

“I remember it was raining and I told myself that I have done everything I can for Egypt and I can retire now,” Shaaban, 65, says.

The four, all veterans of Egypt’s 1970s student movement, had fought long and hard for political reform and were jubilant when the demonstrations against Mubarak gathered pace. But there was a wistfulness too, spurred by the resemblance between Tahrir’s youthful protesters and their own first forays into activism. When they began the struggle, around 1972, the four were still at university. By the time of the anti-Mubarak uprising, many of them were in their sixties.

“Our generation sacrificed a lot,” says El-Wardany. “We suffered with arrests, displacement, the possibility of torture. For nothing. Until 25 January came.”

This generation turned Cairo University and other universities in Egypt into a hotbed for political change. For them, the 2011 uprising was the revolution they had long waited for.

The student movement began in January 1972 and climaxed five years later when the “bread Intifada” broke out and millions of Egyptians took to the street. But the road between the Januaries of 1977 and 2011 wasn’t easy.

Youssef says that in the years between the two, some of her colleagues gave up hope, some left the country, while others like her waited for an uprising they were sure was going to come.

“And then there were those who lived their lives, but whenever January came, something ached inside them,” she said.

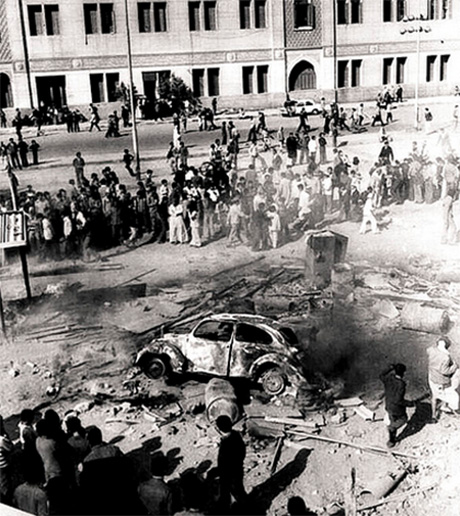

(Photo: Al-Ahram)

From January to January

Through his poetry, Fouad became one of the leaders of the 70s student movement.

His poetry, which was seen by the regime as inflammatory, was often

distributed by students. In 1972, the regime found one of his poems, “extracts from a bloody Thursday,” in 50 universities nationwide.

“I started publishing my poetry and the students started knowing me and would hand copies to one another,” says Fouad, 72.

It was his talent for poetry that sparked his interest in politics. At the age of six, he began going with his older brothers to demonstrations against the British occupation in Egypt. While marching, he would hear his fellow protesters chanting a name over and over.

“It was Abdel Hakem El-Garhy. I was intrigued and wanted to know more,” remembers Fouad.

He began researching and found that El-Garhy was an Egyptian student who was shot by the British in 1935. El-Garhy was walking in a student protest against the occupation on the Abbas Bridge in Giza when they clashed with security forces. One of the students, holding the Egyptian flag was shot down, so El-Garhy picked up the flag.

“At this point, El-Garhy was warned by a British officer not to move. But he ignored him and took 13 steps. With each step, he was shot once, totalling 13 shots,” says Fouad.

On his deathbed, El-Garhy, used his blood to write a scathing message condemning the British occupation of Egypt. The story touched Fouad and he began writing a poem about El-Garhy every 21 February to mark his death.

When Fouad’s 26-year-old brother died in the 1956 Tripartite Aggression on Egypt by Israel, France and Britain, his interest in politics intensified.

“My brother was the first martyr I knew; I was only 14 years old when he died,” he says.

When he enrolled in university in 1960, he began using his poetry as a form of political activism. He remained in university for 12 years, first studying engineering and then transferring to literature.

Although, he says, the student movement took off in 1972, the trigger began in 1967 when Egypt suffered defeat at the hands of Israel in the Six Day War. Not only were the Egyptians — and especially the students — in shock because Gamal Abdel Nasser had assured them of victory, but they were further incensed when the trials of Egyptian air force officers deemed responsible for this defeat ended with light sentences.

In February of 1968, students joined the protests, and their demands expanded to freedom of expression, freedom of the press and a representative parliament.

After Nasser’s death in 1970, the new president, Anwar El-Sadat, did not fare any better with the students.

Shaaban, 65, another leader of the student movement, said that the youth were immediately suspicious of Sadat.

“Nasser was like a father who raised us, educated us, fed us,” says Shaaban. “We saw that he made mistakes, and yes, we revolted against him. But there was love there. Sadat was different. It was very clear from the beginning that he came with a different agenda.”

The bitter taste of the 1967 defeat continued in the early years of Sadat. Israel was on Egypt's doorstep.

“They were a 15-minute plane ride and they would have been here,” says Shaaban.

Sadat promised that 1971 would be the “Year of Decision,” for the conflict with Israel. But 1971 came and went and there was no war.

The outraged students began calling for a sit-in at the biggest hall in Cairo University. The sit-in, which began in the Engineering Department, quickly drew students from other departments and then moved to other universities. The sit-in began on 13 January.

El-Wardany, then only 22-years-old, was one of the students who quickly joined. He was impressed with what he saw as “Athenian-style” democracy at play for the first time in his life.

“But the hall was stormed on 24 January and at least 1,000 students were arrested, including me,” he said.

El-Wardany was released one week later.

Fouad and Shaaban, also detained, weren’t so lucky. The duo were arrested and taken to the Citadel Prison to stay in solitary confinement. Fouad for one and a half years and Shaaban for a year.

Shaaban points out that Sadat believed that the arrests would thwart the student movement. But instead it flourished. The university turned into a “liberated zone, where poets, writers, singers, and anyone who dreamed of change” went.

The students continued their activism.

“I was politically active and they often used to arrest the students during exam times, so I would skip the exams and fail the year,” he smiles.

The Sadat years

In 1974, Sadat began his "open door" (Infitah) policy that included liberalisation of the economy — a departure from Nasser’s socialist system.

“It was basically a move against the economic system that was created to aid the poor majority,” said Shaaban.

The change in the economic system had a massive effect on Egyptian universities. By the time Youssef, enrolled in university in 1975, there were marked class distinctions between the students. Not just that, but clashes broke out between Islamists students and leftists over politics. She remembers once being punched in the shoulder while trying to distribute flyers on campus.

“We never said anything against religion. We were just calling for change,” Youssef says. “We really believe that Sadat empowered these students so that they would fight the leftists on campuses. Because at the end of the day we were proving to be a big problem for him.”

At the time, student demands were many. They were asking for freedom, a diverse press, a multi-party system, and better wages among other things. Revolutionary duo Ahmed Fouad Negm, the poet, and Sheikh Imam, the singer, would make regular visits to the university, firing students up and inspiring them to continue with their activism.

“Sheikh Imam would always end his concerts with the song 'Guevera died,' and he would raise his lute, and the moment he did that, we would be out in the street protesting,” remembers Youssef. “He had that kind of charisma.”

In 1976, Sadat took loans from the World Bank to cover Egypt’s debt with the condition that he would limit state subsidies on food and other commodities. At the same time, Sadat promised the Egyptians prosperity.

“He would give speeches and promise that every Egyptian house would have hot water and happiness,” smiles Youssef.

But on 17 January 1977, Egyptians were shocked when the government announced the removal of subsidies resulting in a sudden price hike.

Youssef and many other politically active students went to the university campus the next day to discuss how to respond. But before they could do anything, the Egyptian people had already taken action, starting with factory workers in the industrial city of Helwan who began demonstrations against the government.

“I remember when I left the campus, I was shocked to see thousands of people in the streets,” remembers Youssef. “It was so congested, you couldn’t even walk, but were pushed forward by the force of the crowd.”

(Photo: Al-Ahram)

Within 48 hours, the Sadat regime backtracked on its decision.

Protests were everywhere from Cairo to Alexandria to Aswan. The leaders of the student movement, like Shaaban and El-Wardany, had fled. Inexperienced, Youssef went home at the end of the first day of protests, only to be arrested at dawn.

She was taken to a police station and then transferred with a friend to the infamous Citadel Prison. While being escorted to her cell, she heard screams.

“It sounded like someone was being tortured, so I began to sing to ease their pain,” she remembers. She remained in detention for over six months.

Fouad was arrested as well. The official charge was “writing poetry against the regime.” He spent 18 months in prison. Shaaban fled when he heard that his name was on the list of detainees. He hid for a few months in Cairo.

“I used to hear that they were going every week and searching for me at home, and at my aunts and uncles. They even went back to my home village. They would literally tear these homes apart while searching,” he says. “My family used to burn our political books out of fear.”

He decided to escape to Lebanon where he remained until 1982. He returned later, but on the condition that he had to serve a one-year sentence in the Citadel Prison.

El-Wardany was also on the run, but still working in politics as part of a secret organisation.

“While on the run, you learn how not be caught and how to dodge government surveillance,” he says. “I mean the whole point of being on the run was to continue to work in politics. And we had to find a way to do it without being captured.”

His political activism continued. He was repeatedly detained in the following years.

Enter the 1980s

Life in Egypt in the 1980s and 1990s was difficult for the four activists. Youssef focussed on raising her two sons. One of them, Ziyad, would later be one of the youth that organised the January 25 Revolution and an MP in the first elected parliament post-revolution. Shaaban worked in publishing, and El-Wardany continued to write novels. Protests continued, but on a much smaller scale.

“With the exception of the worker’s strikes, most of the demonstrations were not about Egypt,” says Youssef. “We supported the Palestinian Intifada, we demonstrated against the invasion of Iraq. Our activism continued, we never stopped.”

They were getting older and their families were growing. But they never saw the demands of their youth materialising.

“Starting from the end of the 1980s, the situation became very depressing,” says El-Wardany. “There was no ray of hope.”

The regime had tightened its grip on everything, says El-Wardany. Newspapers were abundant but rarely free to express their opinion or challenge the regime. Political parties existed but were neither independent nor active. The continuous terror attacks that hit Egypt after Sadat’s assassination in 1981 put the opposition in a tough position.

“We wanted to stand with the state against terrorism, but to stand individually, without becoming involved with the state,” El-Wardany adds.

The spark finally came when the Kefaya (Enough) movement entered the political scene in Egypt in 2004. The movement opposed the Mubarak regime and demanded reform. Protests, albeit small, became a weekly affair. The security apparatus was ruffled enough to send hundreds of state security officers to quickly surround and arrest those involved.

“I was arrested in 2006, when I joined a protest against constitutional amendments,” says El-Wardany. “This was the first time that I felt there is hope.”

In his 50s at the time, El-Wardany found himself detained with youth, who he found were demanding many of the same reforms he and his colleagues wanted in their youth.

The long road to Tahrir

When the January 25 Revolution finally erupted, the generation that had been fighting for 40 years were euphoric.

“For the first time in my life, I saw people retrieving their freedom, creating their own fate, loving and looking out for one another,” El-Wardany says.

Many members of the 70s student movement quickly joined the youth in Tahrir Square.

“We stayed in the square as a way of showing our support for them,” says Fouad. “We wanted to show them that we had their back and we were there for them.”

When Mubarak was ousted, they were elated.

“I felt such happiness at the fall of this tyrant,” says El-Wardany. “He took my life. He came when I was 31 and left when I was 61. That’s my whole life.”

The months and years that ensued after the 18 days were as erratic for them as they were for the bulk of the Egyptians.

They watched as the youth began clashing with the military, which was ruling Egypt after Mubarak’s ouster. They watched as the Muslim Brotherhood came to power and as they fell. And they watched as Egyptians took to the street again on 30 June 2013, soon bringing President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi, then minister of defence, to power.

“I had to backtrack on the plans I made while I was in the square during the 18 days. I could not quit political life again,” says Shaaban. "I felt that our dream was aborted. Once the Brotherhood came to power, I felt that we went back to point zero.”

Shaaban and many of his colleagues were dismayed at the protest law passed in November 2013 that put restrictions on political gatherings. The security apparatus has remained the same, some felt. Many revolutionary youth now had a pessimistic view of the future.

But the situation is not grim, they say.

“We have a long struggle ahead,” Fouad says. “When you are broken, you get up, get yourself together and start again. The revolution does not end with a ballot box. It is complete when its demands are fulfilled.”

Now most of those who participated in the 70s student movement are in their sixties and seventies. Some died along the way. One former student decided to keep track of all those who passed away and create a list to honour them. So far, 121 have gone.

“But when I look at the square (Tahrir), I saw the suffering of all my friends who fought for this. Those in the university and those who ended up in prison,” says Fouad. “I saw their faces in the crowd.”

Short link: