It was supposed to be a peaceful Tuesday afternoon at Al-Ahram, with president Anwar Al-Sadat expected to attend the annual commemorative military parade that honours the memory of the 6 October 1973 War.

Sadat had already arrived at the venue of the parade in Nasr City in Cairo. He was there along with his vice president Hosni Mubarak and his top aides. Also present for the eighth anniversary of the October Crossing was Jihan Al-Sadat, the first lady, who had arrived with Sadat’s beloved grandson.

The parade had started, and Assem Al-Kersh, a former editor of Al-Ahram Weekly who was then a member of the foreign desk of Al-Ahram, was watching the parade with colleagues before suddenly the transmission went down.

“It was an awkward moment; it was very unusual for a transmission to go down unexpectedly, certainly not when the president was making an appearance or attending a high-profile event like the October military parade,” Al-Kersh remembered.

He was not sure what to think. Typically, he checked the wires — “nothing”. The official news agency had not aired an explanation.

An hour later, an evening newspaper came out early in the afternoon with a headline suggesting that Sadat had left for his Delta village of Mit Abul-Kom. The paper further said that upon his arrival in the village, Sadat had visited the grave of his half-brother Atef Sadat, one of the first Egyptian soldiers to have died in the early hours of the October War.

“It was suspicious: the TV would normally air the parade to its end and show the president leaving in his motorcade. Something was odd; it was in the air even if the news was not coming through,” Al-Kersh remembered.

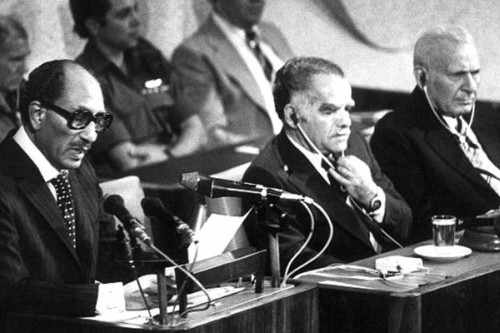

Sadat addressing the Israeli Knesset in 1977

An anxious newsroom was not sure what to put on the front page of Al-Ahram for 7 October. There was no confirmation that Sadat had left Cairo for his village, and there was no other narrative to offer.

Al-Ahram’s editor at the time, Ibrahim Nafie, seemed to know something but was hesitant to share it. This added to the apprehension in the newsroom. Al-Kersh was already trying to contact friends in foreign news agencies, but he was not getting through.

Then, a couple of hours later, the news broke. “Sadat is dead.” The Reuters machine at the foreign desk was ringing, and Al-Kersh jumped up to snatch the dispatch. “It was one line: Sadat is dead, official,” he remembered.

This was shocking news even for this young journalist who had not come to terms with the peace treaty that Sadat had signed a little over two years earlier with Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin with the mediation of US president Jimmy Carter.

He dashed into Nafie’s office, who merely nodded without even having seen the dispatch. By the time Al-Kersh was back in the newsroom to join the team in writing the paper’s headlines, the US news agency AP had given a more detailed account of how Sadat had died during a shooting at the October military parade.

“It is interesting that the AP photographer on the scene had a walky-talky, the first to be allowed for a news agency in Egypt. He reported the developments to the Cairo bureau, which immediately filed the story — but in the rush missed an urgent code, prompting an eight-minute delay behind Reuters whose chief was on site and managed to find his way to a nearby apartment in Nasr City where he was allowed to use the phone and put out the news,” Al-Kersh said.

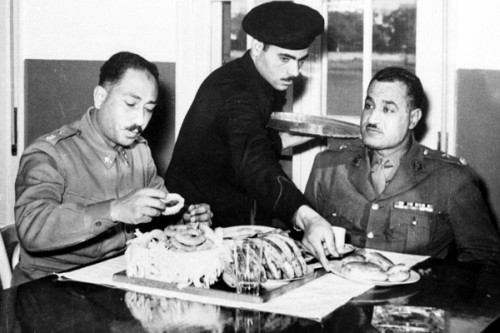

Sadat and Nasser in the military uniform of the Revolutionary Council

“Hosni Mubarak: The hero of war and peace fell as a martyr. We are committed to the peace treaty with Israel.” This was the headline that appeared in Al-Ahram later, alongside a picture of Sadat’s last appearance in military uniform.

The front page in a bold black font carried the statement of then vice president Hosni Mubarak.

Mubarak’s statement was meant to affirm Egypt’s commitment to the peace treaty. The newsroom of Al-Ahram had received a message from the presidency to give prominence to this line.

In his recollections of the day later, Mubarak, who became Sadat’s long-serving successor, said that it was important for him to assert this point to avert any concerns about Egypt’s position on the peace with Israel.

“This was a serious matter,” Mubarak said.

A Ground-Breaking Treaty

According to Al-Kersh, the assassination of Sadat at the hands of members of the Armed Forces at the October military parade was more about the peace treaty than about any of the other controversies that Sadat’s name had been associated with during his 10-year rule from the day he succeeded Gamal Abdel-Nasser as president after the latter’s death in September 1970.

“Sadat’s name should have been most associated with the October Crossing of 1973, but this was not the case. So much had happened since the day Sadat spoke before parliament to announce the crossing of the Suez Canal to the east bank that had been occupied by the Israelis since 1967,” Al-Kersh said.

“Of the many political and economic decisions that Sadat took, and the very high drama that he lived through on the internal and international scenes, he was most associated with the peace treaty with Israel,” he added.

Certainly, Sadat’s funeral, which lacked the public presence that marked Nasser’s, was attended by US presidents Nixon, Ford and Carter along with Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin.

“The peace treaty with Israel was certainly a big deal for the world; this was clear in the news coverage in the foreign press at the time,” Al-Kersh recalled. “When it happened on 26 March 1979, it was a day when we had to do extra editions of Al-Ahram, just like we did with the signing of the Camp David Accords a year earlier when we had eight successive editions, or with Sadat’s surprise visit to Jerusalem in 1977,” Al-Kersh said.

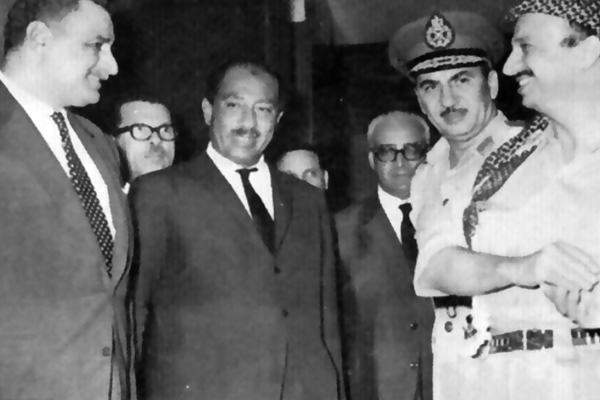

Sadat with Nasser and Arafat

On the evening of Wednesday 9 November 1977, the newsroom of Al-Ahram was again in a state of confusion. In a statement before parliament earlier in the day, Sadat had taken the world and the People’s Assembly and the attending Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat by surprise when he deviated from a written speech to say that he was willing to “go to the end of the world, to the very house of Israel, the Knesset itself,” in search of a peace that would spare the further bloodshed of Egyptian soldiers.

The news team at Al-Ahram had already followed the televised statement with surprise, only matched by the surprise that Arafat expressed to foreign minister Ismail Fahmi who had invited him to come to Egypt to attend Sadat’s speech.

“We were not sure what to do; initially, we had the statement in the headlines, but then we received a call from the office of Fahmi to ask us to remove any reference to this statement. Then there came a call from the presidential press office requesting the statement to be in the headlines. There was total confusion, but eventually we had the statement in the headlines,” Al-Kersh recalled.

In his memoirs, Negotiating for Middle East Peace, Fahmi later wrote that it was on the request of Sadat personally that he had called Al-Ahram to request that the reference to his willingness to visit Jerusalem and to make a statement before the Knesset be removed.

“He told me it was a slip of the tongue, and that I needed to have it removed,” Fahmi wrote.

According to his memoirs, Fahmi had heard Sadat earlier contemplating the idea of visiting Jerusalem in pursuit of a peace deal. He had made a reference to his “willingness to go to the Knesset in pursuit of a peace that would end the bloodshed of Egyptian soldiers” during a meeting of the National Security Council on 5 November and his remark was contested by chief of staff Abdel-Ghani Al-Gamassi.

This, however, was not the first reference that Fahmi had heard from Sadat about the visit. In his memoirs, the foreign minister, who resigned upon Sadat’s actual visit to Jerusalem on 19 November the same year, wrote that Sadat had brought the issue up during a presidential visit to Romania where then president Nicolai Ceausescu had conveyed to him a message from Begin expressing a willingness to meet for peace.

Sadat, Fahmi added, had already sent a personal envoy to Morocco to meet with Israeli officials to explore their wish for a meeting. Later, despite the firm opposition of his foreign minister and other top aides, Sadat decided to go ahead with the visit. Fahmi decided to send his resignation to Sadat’s vice president Mubarak only two days before the scheduled visit began.

In his memoirs, former foreign minister and Arab League secretary-general Amr Moussa wrote that Mubarak had a clear recollection of the incident. Mubarak, Moussa wrote, was instructed by Sadat to accept the resignation of Fahmi and to make the news public.

Sadat with the military staff in the operations room of the 1973 War

Sadat, also according to Moussa’s memoirs, then requested minister of state Mohamed Riad to be sworn in as foreign minister. Riad declined, and he was asked to resign. Boutros Boutros-Ghali was then sworn in as minister of state for foreign affairs and he joined Mubarak as he arrived in Jerusalem on the Saturday evening, 19 November 1979.

“It was the eve of the Muslim pilgrimage feast. I was there with my family in Alexandria for the occasion. We were watching Sadat’s arrival in Jerusalem with a great sense of surprise,” Moussa wrote.

He added that it was “a big moment for sure; still, it was very perplexing for us as young men who had grown up with the successive wars with Israel to see our very own president, the head of the leading Arab state, arriving in Jerusalem to be received by the leading officials of Israel. This visit shook the ideas we had grown up with and lived with for years and years.”

Moussa thought that “it was inevitable for us to go to negotiations with Israel, but I did not expect it to happen in such a dramatic way.”

In the autumn of 1977, Moussa, he wrote in his memoirs, thought that maybe Sadat should not have gone himself. However, some years down the road, it was clear that “the shock caused by Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem was necessary for the prompt negotiations that allowed for the peace process to bring Sinai back to Egypt.”

“In short, I am one of those who believe that without the bravery of Sadat and his willingness to take such a dramatic step that literally put Israel in the corner, it would not have been possible for us to have retrieved all of Sinai maybe until today,” Moussa wrote in his memoirs that came out in 2017.

The details of the Jerusalem visit and the subsequent negotiations leading to the signing of the Camp David Accords in 1978 and then the peace treaty in 1979 are also recalled in the memoirs of Boutros Boutros-Ghali, The Road to Jerusalem, and in the memoirs of Ibrahim Kamel, Egypt’s foreign minister from December 1977 to September 1978.

The narratives share most of the details of the Egyptian-Israeli talks that allowed for the signing of the Camp David Accords and the peace treaty. However, they do offer opposing perspectives.

In Boutros-Ghali’s memoirs, Sadat is a shrewd politician who manoeuvres the Israelis to his objectives of liberating Egyptian territory and setting the groundwork for a larger Arab-Israeli peace that would eventually allow for the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Sadat’s wedding picture with Jihan

In the memoirs of Kamel, who resigned on the eve of the signing of the Camp David Accords, Sadat is a man with good intentions but a rushed schedule to reach a deal at any price and with insufficient guarantees that the peace deal between Egypt and Israel would not come at the expense of other Arab countries whose territories were still occupied by Israel or at the expense of the Palestinians.

40 Years On: “Today, when one looks back, one says, well, even if one disagreed with what Sadat did at the time, one has to give him credit for having had the very clear objective of liberating Egyptian territory, which is what he did,” said a retired Palestinian official.

He added that unlike Nasser, who viewed himself as an Arab leader with responsibilities that took in all the Arab countries, Sadat was more of an Egypt-first president whose prime focus of attention was to restore the occupied Egyptian territories.

“I guess what we should have thought of back then was that what Sadat was doing was a clear sign about the changing of the times, but we did not. We thought that he would be somehow stopped, or that the Arab opposition to his peace treaty would force him to do a U-turn. But he didn’t because his objective was not to be another Arab leader like Nasser but to be the Egyptian president who had liberated the land that Nasser had lost,” added the official.

Not long after the signing of the peace treaty, an Arab Summit in Baghdad decided to suspend Egypt’s membership of the Arab League and to remove the headquarters of the Pan-Arab organisation to Tunis.

A few years later, following the assassination of Sadat and the subsequent ascent of Hosni Mubarak to power, this decision was reversed. According to statements that Mubarak made later, the return of Egypt to the Arab League and the return of the Arab League headquarters to Cairo was not just a matter of realism but also an indication of the unannounced fact that Sadat’s visit might have been opposed by all the Arab leaders in public, but in private some did not really oppose it.

According to a former Egyptian foreign minister, at least five Arab countries, including more than one Gulf state, were not really opposed to the Jerusalem visit or to the peace treaty.

“Nobody wanted another war. Several Arab capitals thought that the successive Arab-Israeli wars had neither served Arab interests in general nor the objective of Palestinian statehood. They thought that a negotiated deal was a better scenario, especially with the unmasked US bias towards Israel and the hesitation of the Soviet Union, before the end of the Cold War, to be supportive of the Arab countries.”

In separate remarks, Arab and Israeli diplomats acknowledged the “open secret” that before and after the Sadat visit to Jerusalem and the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, there had always been channels of communication, more indirect than now, between Israel and the representative of several Arab regimes.

Four decades down the road, Israeli prime minister Benyamin Netanyahu is now openly bragging about the many direct contacts he has had with most Arab capitals even at a time when the hope for Palestinian statehood is remote.

However, according to a Palestinian politician, the “very sad situation in which the Palestinians stand today, completely coerced by Israel and with hardly any backing from the Arab world, started when Sadat chose to unilaterally sign a peace treaty with Israel irrespective of what that meant for Palestinian rights.”

“We all know that Israel was willing to do anything to get Egypt out of the Arab-Israeli struggle. Once Egypt was out, Jordan was going to follow. It did not matter very much whether or not Syria, or for that matter Lebanon, would come to sign a peace deal, because I don’t think Israel had the intention to give up the Golan Heights as it did with Sinai,” the politician added.

“As for the Palestinians, well, Israel was not planning to bow to their right of statehood back in 1977 or 1979 or any other time, as it is not willing today to agree to this right,” he stated.

In his criticism of Sadat’s peace initiative and subsequent peace treaty, the prominent commentator Mohamed Hassanein Heikal wrote in his book The Debate over the Initiative that when the Israeli delegation arrived in Egypt in the wake of Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem for the launch of talks at the Mena House meeting supposed to bring all Arab parties along with Israel to the negotiating table, the head of the Israeli delegation objected to having the flag of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in the meeting room.

According to Heikal, the Egyptian organisers of the meeting removed the flag and told the Israeli delegation that the flag of the PLO had been put there at the initiative of the hotel management without official instructions.

For Heikal, this was one of many incidents that made it clear that what Israel was out to get was a peace deal that would negate any future Egyptian influence on the path of the Arab-Israeli struggle.

A similar sentiment is expressed by writer Youssef Idris in his book The Search for Al-Sadat. A novelist and commentator who had previously had relatively close relations with Sadat, Idris wrote that his support for Sadat’s peace initiative lasted no more than four weeks before it became clear that it was not the outcome of an orchestrated Arab diplomatic plan but rather a “caprice” of Sadat’s.

According to both Heikal and Idris, peace cannot be built upon one’s man wishes, no matter how sincere and no matter how passionate.

In Retrospect: Esmat Seif Al-Dawla is the founder and chair of the Egyptians Against Zionism Forum and an ardent critic of Egypt’s “unilateral peace with Israel” that he says “was not just about ending the state of war and the occupation of Israel in return for normal relations, but was essentially about bringing an end to Egypt as a leading Arab state capable, despite the economic hardships, of overcoming the Israeli occupation of its territories in 1967 with the crossing of October 1973.”

“Israel had not expected that Egypt, harshly defeated in 1967, would be able to organise the crossing six years later. This kind of Egypt was a threat to Israel, and it had to be changed once and for all by another Egypt that had abandoned its responsibility towards the Palestinian cause and its ability to be an independent state,” Seif Al-Dawla said.

He argued that the path towards the 1979 treaty was initiated much earlier than the 1977 visit. It was started, he said, with the “extremely unfair arrangements” of Sinai first and second agreements that allowed for the end of hostilities between Egypt and Israel in the wake of the ceasefire of the October 1973 War.

After the agreement, Seif Al-Dawla argued, Sadat, “already stripped of any regional influence,” chose to pursue uncertain economic and political choices. On the economic front, he opted for a free-market economy, for example. “This simply meant that he abandoned the public sector, which was the basis of the national economy that allowed for social equality and had been essential for the October crossing,” Seif Al-Dawla argued.

With the inflow of US economic aid, Seif Al-Dawla added, Sadat allowed for the launch of a new socio-economic stratum of “businessmen who made huge fortunes and chose in return to support whichever policies that Sadat was adopting in return for their new-found affluence.”

This, he added, meant the beginning of the erosion of the middle classes that were essential to the stability of society.

Sadat with the then vice president Hosni Mubarak

In parallel, Seif Al-Dawla added, Sadat was not willing to allow for any serious opposition to the peace treaty with Israel, so he chose “to coerce all national political forces that opposed this Treaty, whether from the left that he had always been at odds with, or from the Islamist quarters that he had originally given a push to in attempts to corner the left.”

Seif Al-Dawla argued that when he quelled the national movement, Sadat unintentionally gave rise to the “cause of a religious identity over national identity, which meant that people felt less Egyptian and more Muslim or Copt”.

On the political front, Seif Al-Dawla argued, Sadat chose to go the extra mile in embracing the US to the point where he was simply following US policies rather than being a partner in them. But the worst part about the peace treaty, in the analysis of Seif Al-Dawla, was the security agreements reached with Israel.

Seif Al-Dawla argued that these agreements, enshrined in the Camp David Accords, meant that Egypt would only have very limited sovereignty over Sinai. “The maximum number of soldiers Egypt is allowed to have in Sinai is way beneath the number required for Egypt to be able to shield itself against any possible attack. This is unforgivable,” he said.

Seif Al-Dawla argued that the realisation on the part of Sadat’s successor Hosni Mubarak that Egypt was not in a position to be able to protect Sinai against a possible Israeli attack was perhaps the reason why he hesitated to bring in a serious development plan for Sinai.

Today, Seif Al-Dawla argued, Egypt “needs to go through security coordination mechanisms with Israel” before it can expand the number of troops or equipment in Sinai to deter radical militant groups.

According to Amin Iskandar, a Nasserist politician and writer, “in retrospect, the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel was perhaps one of the many mistakes that Sadat made during his rule of Egypt. In fact, it is perhaps the root of the many mistakes he made.”

It was the worst, he explained, because it would be very hard to have it reversed without getting into a confrontation today, not just with Israel but also with other world powers.

It was also the worst, he added, because its impact was far-reaching. “It was not just about Egypt, but about the entire Arab world,” Iskandar stated.

But for Gamal Abdel-Gawwad, a political analyst at the Al-Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo, “in retrospect, there was perhaps no other way than Sadat’s way to regain all the Egyptian territories that had been occupied by Israel in 1967 and to move on beyond the phases of subsequent wars with Israel that were becoming impossible to manage from an economic point of view.”

According to Abdel-Gawwad, while many argued back then, and some still do today, that Sadat could have continued the military path to complete the liberation of Egyptian territories and pave the way for Palestinian statehood, “this was in fact an unrealistic path.”

Egypt, he said, could not have managed another “surprise war” against Israel. The US had come to the rescue of Israel in a direct way, while the former Soviet Union had been hesitant about providing Egypt with the necessary military equipment. The Egyptians could not have taken another military defeat from Israel.

“A negotiated settlement was the only way out for Egypt, and in a negotiated settlement it is inevitable that you give something and take something. What you give and what you take depends on the balance of power,” he said.

Sadat with the then vice president Hosni Mubarak

Egypt was “in no position” to wait for all the Arab countries to come to an agreement with Israel or for the Palestinians and Israelis to reach an agreement, he said. “It was not possible because stability in Egypt is always dependent on the sovereignty of the state over its territories. The quality of this sovereignty is another story,” he said.

Moreover, Abdel-Gawwad added, the debate over the quality of sovereignty over Sinai cannot be assessed strictly on the military and political performance of Sadat. The political and military performance of Nasser, who had actually lost this land to Israel, has to be factored into the assessment as well.

“The fact that four decades after the treaty, Israel has not violated its commitments and Sinai is still under Egyptian sovereignty, despite whatever remarks one might have on the text of the peace treaty, is what really counts,” Abdel-Gawwad said.

He added that “in the final analysis, Sadat came to office with Sinai occupied, and he died after he had liberated Sinai, partially by war and partially by peace.”

The Rule Of Sadat: In the view of Iskandar, the rule of Sadat can be divided into two phases: before the peace initiative and the subsequent peace treaty and after it.

Iskandar argued that until the October War, Sadat was guided by the “firm wish for a war to liberate the land that Israel had taken by force in 1967.”

“His focus was war, but he still acted to sideline all shades of political opposition whether from within or without the regime. He wished to cut the ways with the concepts of Pan-Arabism and socialism that were essential pillars of the rule of Egypt before he took over,” Iskandar argued.

After the October War, he added, Sadat “re-launched himself not as the successor of Nasser but as the ‘hero of the crossing’. Then came a litany of US-inspired economic and political moves that prompted a great deal of social unease until he went ahead with the signing of a peace treaty that even many of those who were willing to support a negotiated settlement with Israel believed was an unfair agreement.”

After the treaty with Israel, Iskandar argued, Sadat accentuated his wish to re-launch Egypt as a country different from the one that Nasser had ruled. “And he was not willing to accommodate any disagreement, explaining the decisions he made in September 1981, only a few weeks before his assassination, to arrest figures of the political opposition who were all still in jail on 6 October 1981,” Iskandar said.

Iskandar blames the second part of Sadat’s rule for “huge mistakes”, including the upsurge of sectarian strife that was blamed on Sadat’s pursuit of an Islamist profile “as a Muslim president of a Muslim land”.

For Iskandar, this was far from being a manifestation of an Islamist bias, but was rather a function of the beginnings of a later time’s association with Saudi Arabia.

An obvious result of this wave, Iskandar argued, was “the unfortunate decision of the Church and the Copts to abandon the public space and to cluster together.”

Iskandar also blames the second part of Sadat’s rule for “an artificial pursuit of political pluralism that was not actually designed to allow real political diversity, but was rather a pretence”.

Iskandar argued that Sadat, in the second part of his rule, was thinking that “he could get away with everything because the world, especially Israel and the US, would support him in return for the otherwise unimaginable political favour that he had done them with the signing of a unilateral peace treaty.”

However, political researcher Amr Al-Shobaky, at the time against Sadat’s unilateral peace with Israel and the subsequent set of political decisions that he adopted, is now willing to subject his past views to considered revision.

“When one sees how things have unfolded on the political scene worldwide, with the end of the Cold War and the rise of the influence of the Arab Gulf countries with the oil boom, it is hard to think that there was another way for Sadat to secure the liberation of Egyptian territories after the shock caused by the October crossing,” he said.

That said, for Al-Shobaky, the October War is perhaps the thing that Sadat should be remembered for rather than the peace treaty.

Al-Shobaky argued that today Sadat should get credit for having seen early on that Arab disagreement would always be a handicap in any serious collective effort to secure Palestinian statehood. He said that the inter-Arab fighting that had started between the Palestinians and Jordanians in 1970 before the death of Nasser had continued well beyond Sadat with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and has since been unfolding.

“Ultimately, Sadat was an Egypt-firster. This is what he thought, and this is how he made his political choices,” Al-Shobaky added.

Even if Nasser initiated the early preparations for the crossing right after the humiliating defeat of 1967, it was still a huge decision for Sadat to have taken because it was ultimately an enormous risk despite all the planning and the heroic courage of the Egyptian military at the time, he said.

Abdel-Gawwad agreed that there was no one in October 1973 who could say in no uncertain terms that the crossing would succeed or that things would not take a humiliating turn. He argued that decades down the road, some still tend to underestimate what the war was really about.

Cold Peace: In his 2004 book The Yom Kippur War, Ibrahim Rabinovich, a Jerusalem Post reporter who covered the war, offers a detailed account of the day of 6 October 1973 when “the Egyptians crossed in strength.”

Rabinovich wrote that “not since the construction of the Pyramids, at least not since the construction of the Suez Canal, had Egypt seen such a massive and well-executed enterprise.”

Seif Al-Dawla argued that what Sadat did after the ceasefire in the autumn of 1973 until he died in the autumn of 1981 simply unrolled the heroism of the crossing. Abdel-Gawwad for his part argued that had it not been for what Sadat did in 1977, what had been secured in 1973 could have been lost at one point or the other.

Meanwhile, Israeli officials have complained that while Egypt has honourably respected its responsibilities under the peace treaty, the peace between Egypt and Israel “remains a cold peace.

In the words of a Cairo-based western diplomat who has served in Israel, “the Israelis cannot understand why relations with Egypt are so cold; they say that what they have with Egypt is normalisation not one.”

In the memoirs he published upon his retirement, Saad Mortada, Egypt’s first ambassador to Israel, describes an awkward arrival in Tel Aviv that was never smoothed by the willingness of Israeli officials to show him hospitality.

“On 26 February 1980, I presented my accreditation in Israel… and I have to say there was a big difference between the welcome I was accorded by the Israeli government and the Israeli people and between the uptight reaction with which Israel’s first ambassador to Egypt was received,” he wrote.

During his three decades of rule, Mubarak would always remind Israeli interlocutors in private, as in public, that for peace to depart from its point of initiation, for which he always credited Sadat, Israel needed to make progress in its negotiations with the Palestinians.

Mubarak would argue that the Israeli rulers needed to be as brave as Sadat in their pursuit of peace.

However, some foreign diplomats in Cairo who attended an event held by the US Embassy to celebrate 40 years of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty suggested that the impression of the Israeli diplomatic corps in Egypt was that it was unlikely that the new Israeli ambassador to Egypt, expected to present her accreditation later this year to President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi, will find a different public posture.

“Official relations between Egypt and Israel are at an all-time high since the signing of the Treaty, Egyptian officials say it and the Israelis also say it, and this week Netanyahu lifted a long-standing Israeli objection to an Egyptian purchase of German submarines. But this is not at all reflected at the public level,” said one of the diplomats following his participation.

Hassan, Ali and Maguida are three Ain Shams University students in Cairo. They come from relatively privileged socio-economic backgrounds and are all under 20 years old. None of them come from families with any particularly anti-Israeli sentiment. And none of them have any awareness of being from families who lost members during the October War or any of the previous wars with Israel.

However, the three, who study different disciplines, said that they would not wish to have anything to do with Israel.

The reason, the three of them agreed, was the continued Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories and the Israeli aggression towards the Palestinians. According to Al-Shobaky this testimony is a mild but significant indication of where “Egypt really stands on relations with Israel.”

“Sadat, upon his visit to Jerusalem and the signing of the peace treaty with Israel, spoke of what he called the ‘psychological barrier’ between Egyptians and Israelis. Clearly, this barrier has only come down at the official level and to an extent at the level of the business community that was manufactured in the wake of the treaty to serve the vision of Sadat, the Americans and the Israelis for normal relations. But things have not changed at the public level,” he said.

Al-Kersh agreed that for the newsroom of Al-Ahram on the eve of Sadat’s funeral it was difficult to find pictures of people grieving as had been the case upon the death of Nasser a decade earlier.

Al-Shobaky argued that while over two-thirds of Egypt’s population of 100 million was born in “the so-called years of peace with Israel”, the overwhelming sentiment is that Egypt is in a state of no war but not in a state of normal relations with Israel.”

“So, while in a sense it would be hard to say that the overwhelming sentiment of the population was opposed to the treaty, it is harder to say that Egyptians really embraced Sadat’s call for peace,” Al-Kersh said.

According to Iskandar, “the peace was not between Egyptians and Israelis, but between the Israelis and Sadat.”

In the view of poet Amin Haddad, there is perhaps no stronger evidence for the lack of affinity between Egyptians and the peace treaty than the flow of satirical songs that came out against Sadat from the leading poets of the time, colloquial poets Ahmed Fouad Negm and Sheikh Imam.

“This is an obvious contrast to the spontaneous flow of passionate national songs, essentially but not only in the colloquial, that came out before, during and after the October War, and even during and after the defeat of 1967 under Nasser,” Haddad argued.

According to Heikal’s book on Sadat’s peace initiative, “peace in the Middle East could not have been made by the will of one man alone.”

Visionary Leader Or Gambler: In his book Al-Sadat between Myth and Reality, Moussa Sabri, a journalist and commentator, describes Sadat, whom he had met in jail in the 1940s for his resistance to the British occupation, as a man of “great resolve” and “unwavering imagination”.

Sabri, a close confidant of Sadat during the Jerusalem visit, recalled in his book, which came out a few years after the assassination in October 1981, how Sadat would listen carefully to diverse political views, “without saying much, or without saying anything at all”, and how he would sing songs by Egypt’s divas at the time, Asmahan and Um Kolthoum, while contemplating an escape from jail.

These traits, Sabri wrote, were constants of Sadat’s and were reflected at times of major political decisions such as the war with Israel in 1973 and the peace with Israel in 1977.

Another book issued after the assassination of Sadat by another confidant, the journalist Anis Mansour, describes Sadat as a man with a calculating mind but also as a man who was not willing to confine himself to the prevailing norms. Both Sabri and Mansour describe what the political elite in Egypt might have expected of Sadat when he walked in the footsteps of Nasser, his charismatic predecessor.

Sadat would never have accepted simply to follow in Nasser’s footsteps because he was a man who liked to leave his own imprint even at great risk to himself, Sabri and Mansour suggested.

Political science professor Ashraf Al-Sherif acknowledges these traits. However, he argues that in the final analysis Sadat “represented the aspirations and dilemmas of the Egyptian political movement since its launch in the 1919 Revolution.”

Al-Sherif argues that when Sadat was born on 25 December 1918 at the time of the 1919 Revolution, the political movement in Egypt was focused on an independent Egypt that had a particular regional status and good international relations.

Like all the rulers of Egypt from the time of Mohamed Ali in the 19th century until today, Sadat acted to establish his legitimacy by protecting and modernising Egypt, Al-Sherif said. Like them, Sadat was only willing to allow democracy at arm’s length.

Al-Sherif disagrees that Sadat diverted from the political path established in 1952 upon the army’s takeover of the country and the eventual elimination of the monarchy and the former ruling Mohamed Ali family. “I would say that he just re-routed,” Al-Sherif said. “Sadat is a very good example of the mainstream of Egyptian politics,” he argued.

However, he added that unlike other political leaders of the past century, Sadat was a man “of high drama who always liked to keep his cards close to his chest, and he acted to conceal his true intentions with theatrical acts. This is why some perceived him as unguided and others saw him as gambler,” he stated.

Today, according to Al-Sherif, himself of the generation born in the decade following the peace treaty, there is “perhaps an attempt at an impartial and dispassionate reading” of the history of Egyptian-Israeli relations. In this perspective, Sadat could be seen as the man who started a path that allowed for the return of the Egyptian territories occupied under Nasser.

For most of the Egyptian population today, Al-Sherif argued, Sadat’s name is most associated with this issue rather any of the other controversial events his name could be associated with in the minds of others.

It would be untypical for an Egyptian man or woman in their twenties to associate the name of Sadat with the Open Door economic policy or incidents of sectarian strife or for that matter an uninhibited approach towards democracy. “If they were asked, they would inevitably refer to one of two things: the October War or the peace treaty,” with the latter being more likely due to the fact that Sadat himself had anticipated the 1973 War as the last of wars between Arabs and Israelis.

Al-Sherif added that consequent acts of Israeli aggression, including the invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and other attacks that have followed against Lebanon and the Palestinians, have failed to make Egyptians born after the treaty perceive that there is peace in the Middle East. But “this is one thing and the perception of Sadat is another,” he said.

According to Fady, Adel and Noha, three students at Cairo University who study science and the humanities, the blame for the failure of the peace treaty cannot be put at the doorstep of Sadat, who did take the decision to restore Egyptian territory. Rather, it should be placed at the doorstep of Israel, which has never been candid about peace with its Arab neighbours or about granting Palestinians their legitimate rights.

They added that perhaps some of the blame should be put on subsequent generations of Arab leaders who have not supported Arab rights as they should have done and have instead focused on using the Palestinian situation to serve their own undemocratic style of rule.

“Sadat was not democratic, but he was brave enough to go to war and to peace with Israel to liberate Egyptian territory,” Fady said, who added that he did not know of anyone in his age bracket who would call Sadat either a “political clown”, “a gambler”, or “a traitor”.

“These are things of the past,” he said. “People might not call him brave or visionary either, however. They just think of him as one of the presidents there during the years of war with Israel and there for the end of wars with Israel,” Fady added.

For Fady’s generation, it is unclear whether the assassination of Sadat was a result of the fury at his economic measures that were not coupled with a genuinely democratic approach or with the controversial peace treaty with Israel.

“The fact of the matter is that even after Sadat was killed the peace treaty lived. It lived throughout Sadat’s immediate successor Hosni Mubarak’ rule, it lived after the 25 January Revolution, and it still is living today,” Fady said.

In her memoirs, A Woman of Egypt, Jihan Al-Sadat is convinced that it was his call for peace that brought about the killing of Sadat because it was too visionary and too revolutionary at the time.

“Even though I had always known that my husband might be killed for his courage and his vision of peace, I was not prepared” for it when it happened, she wrote.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 28 March, 2019 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: Sadat and the peace treaty

Short link: