Egypt’s government announced in October that a new personal status law is being prepared by a committee at the Ministry of Justice.

The committee should complete the final draft of the bill by the beginning of 2020, and then it will be sent to the cabinet for approval, before being referred to parliament.

The term “personal status law” is roughly equivalent to the idea of family law in Western countries, covering issues such as marriage, divorce, alimony and child custody.

For four years, since the convening of the current parliament in 2016, discussions have been going on around amending Egypt’s current corpus of personal status legislation, or issuing a new law.

According to public statements by a number of MPs, the process is taking a long time due to the sensitivity of the subject and the need to have a social dialogue on the issue.

Mohamed Abu Hamed, an MP and undersecretary of parliament’s solidarity and family committee, told France 24 that delegations of parents who have had problems because of the law have visited parliament over the past four years.

Although they had different views on the existing law, they all agreed it is not suitable for the contemporary world, he said, and is not able to keep up with social changes and the challenges that face Egyptian families.

There are currently four laws on personal status in Egypt: Law 25 of 1920 and its amendments, Law 25 of 1929 and its amendments, Law 1 of 2000, and Law 10 of 2014.

According to the Ministry of Justice, there are around 163,000 cases on average filed annually before the family courts that adjudicate these laws.

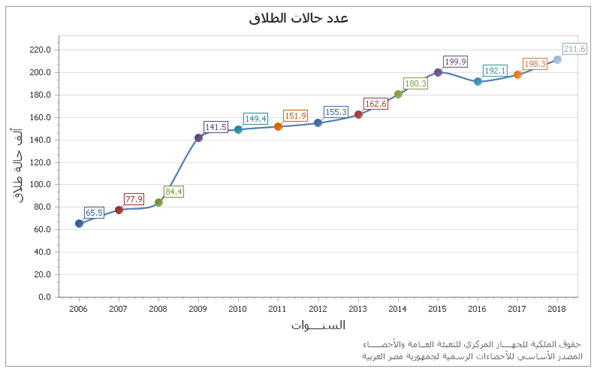

Divorce rates have increased significantly in Egypt during the recent past. According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the divorce rate has increased from 2.1 cases per thousand people in 2017 to 2.2 per thousand in 2018, while rates of new marriages across the country decreased.

Main points in NCW’s draft law

Given the increase in divorces, many observers argue that family law must be updated to keep up with a growing phenomenon.

Some even demand that any new or updated law should account for pre-marital procedures, or should mandate that engaged couples be required to take classes before marriage, to help decrease the possibility of divorce.

Who has presented suggestions and draft laws?

Different suggestions, including both amendments to existing legislation and new bills, have been presented to the Egyptian parliament by a variety of different people and groups, including individual MPs, Egypt’s state women’s council, and religious institutions like Al-Azhar.

In 2016, MP Sohair El-Hadi presented a draft law for child custody that stirred up a lot of controversy and was criticised by the National Council for Women (NCW), as it suggested more child visitation rights for the non-custodial parent after a divorce.

MPs Mohamed Fouad and Abla El-Hawary have also presented their individual suggested bills, and the Wafd Party presented a draft law to the parliament in 2018.

The National Council for Women also presented a draft personal status law in early 2019.

Number of divorce cases in Egypt from 2006 to 2018 (photo: CAPMAS)

The different suggestions were sent to Al-Azhar for feedback, and to judge their compatibility with Islamic sharia. Al-Azhar, however, did not respond to suggestions. Instead, it recently presented a draft law prepared by its Council of Senior Scholars.

The Sunni institution is an important component of the process of changing the law, as the Egyptian constitution states that “the principles of Islamic sharia are the principal source of legislation.” In Egypt, the family law topics regulated by personal status law are considered to be matters relevant to religious legal scholars.

Which law is likely to pass?

According to parliament’s regulations, the law will be discussed by a joint parliamentary committee in a “comparative table.” The government’s draft law, when released, will be the primary law, and all the other proposals and draft laws will be looked at in comparison with it.

The committee will choose articles from the suggestions and formulate them in a manner that accommodates different perspectives.

Below, Ahram Online breaks down some of the most controversial topics in the personal status law, and the alternatives presented by different parties.

Child custody: Prioritising women’s custody

Current status:

The right of child custody is given to the mother, then female relatives from the mother's side who the child is not permitted to marry under Islamic law (including various blood, step and foster relatives), then the father himself and then male unmarriageable relatives.

Suggestions:

The Wafd Party and some other MPs have suggested that the father should directly follow the mother in custody rights.

The NCW and Al-Azhar suggest maintaining the status quo.

Child custody: Age

Current status:

Law 25 of 1929 states that the right to custody of the mother or other female relative ends at the age of 10 for boys and 12 for girls. However, Law 4 of 2005 changed the ages to 15 for both boys and girls. After the age of 15, the child is asked to choose with whom they would like to live.

Suggestions:

The Wafd Party and independent MP Mohamed Fouad suggested that women’s custody end at age nine for both girls and boys.

The NCW suggests maintaining the status quo.

Child custody: Visitation rights and travel permission

Current status:

The current law states that the non-custodial parent should see the child in a place the custodial parent agrees on, or is decided by the court, for a period not less than 3 hours per week, preferably on holidays.

Suggestions:

There are suggestions to increase the visitation period; the Wafd Party, for instance,has suggested increasing the visitation period to five hours.

Some have suggested that instead of the three-hour visits, the non-custodial parent should be allowed to have the child overnight. MP Mohamed Fouad suggests that the period should be between 24 and 48 hours per week, and half of a vacation period.

However, many women and women’s rights advocates and organisations fear that the non-custodial parent might kidnap the child if they were allowed to take them overnight, while some claim this happens now under the existing law.

Lots of parties, including the National Council for Women and Al-Azhar, suggested there be a prohibition on changing the names of children whose parents are divorced, or banning them from traveling abroad, without the consent of the custodial parent or the permission of the judge, to prevent kidnapping.

Child custody: Educational decisions

Current status:

In the case of both ordinary divorce or khula (a wife-requested divorce), the custodial parent (mother) is the child’s guardian in educational matters, according to the child’s law, Law 12 of 1996, and its amendments.

Suggestions:

Al-Azhar suggested joint educational guardianship between parents in its draft law; however, in the case of disputes, the father would have final say, and he would have to pay for the child’s education. If the custodial parent wanted a more expensive type of education, they would have to pay the difference in price.

The Wafd Party suggested that the father should be the sole educational guardian.

Polygamy

Current status:

Egyptian Muslim men are entitled to have up to four wives concurrently.

According to Article 11 of Law 25 of 1920 and its amendments, the husband must cite his marital status in a marriage contract.

Wives are entitled to seek divorce if their husband marries another woman, if she discovers that her husband was already married at the time of their marriage, and if she stipulated in her marriage contract that she would not accept a polygamous marriage.

Suggestions:

The National Council for Women suggested that the judge should make sure the first wife is informed and approves of her husband’s other marriages.

MP Abla El Hawary in 2018 suggested an amendment that would see men who remarry without informing an existing wife punished with six months’ imprisonment.

Customary marriages

Current status:

Customary (urfi) marriages are marriages that are considered valid in Sunni Islam but have not been registered with the state.

Under existing law, a wife can file a lawsuit to prove the validity of an marriage with an urfi marriage contract and will then be able to get the required marital maintenance from her husband, or alimony in the case of divorce.

A customary marriage can also be proven by other methods like witness testimony.

Family courts can use urfi marriage contracts as proof of paternity.

Suggestions:

The National Council for Women suggested putting in place a five-year time limit for registering urfi marriage contracts.

Some MPs, like Amenah Nossier, have suggested urfi marriages be criminalized.

Others, like the president of the Cairo Court of Appeals, suggested the annulment of any legal frameworks that permit urfi marriage.

Wives’ obedience

Current status:

Article 11 in Law 25 of 1929 states that if the wife refuses to obey the husband without good reason, her required financial maintenance stops from the date of her disobedience.

The article also states that the wife’s refusal to return to the matrimonial home after the husband has invited her to return by declaration is unlawful, and she would be considered recalcitrant (nashiz) and deprived from her legal rights as a wife, including maintenance and alimony. The wife can challenge this before the court within thirty days from the announcement.

Suggestions:

The National Council for Women and some others suggested the total cancelation of the articles regulating wives’ obedience.

Engagement

Current status:

There are currently no laws regulating the engagement period, its financial aspects or the pre-marital procedures in Egypt. The matter is governed mainly by customs and traditions that vary across the different regions. There is typically an exchange of rings and the groom gives the bride a shabka, a gift of jewelry, usually gold, to mark the engagement.

Suggestions:

Al-Azhar, the National Council for Women, the Wafd Party and others have suggested laws covering the engagement period, and regulating financial aspects in case of annulment of the engagement, like the gifts that have been exchanged and the shabka.

Short link: