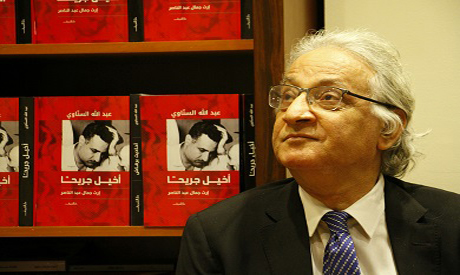

Abdallah Sennawi with his book

Akhil Garihan (Achilles wounded), Abdallah El-Sennawi (Cairo, Dar El-Shorouk, 2019)

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the death of Gamal Abdel-Nasser, Egypt’s most legendary and forever controversial president, Abdallah El-Sennawi, a journalist and political commentator with hardcore Nasserist affiliations, released a book revisiting Nasser’s legacy.

Akhil Garihan (Achilles wounded) was published towards the end of 2019 by Dar El-Shorouk, with a dedication from the author to “the coming generations.”

With such a dedication, Sennawi put himself exactly where he wanted to be: not addressing those who lived under Nasser, but rather the generations born decades after Egypt paid tribute to Nasser with a public funeral attended by millions in September 1970.

Sennawi’s book, which is close to 400 pages, is an unabashed defence of Nasser’s legacy – which Sennawi said has been treated incredibly unfairly. The author's defence could not have been more thorough.

According to the 14 chapters of this book, anyone else but Nasser is to blame for almost everything that happened during Nasser’s rule of Egypt from 1954 to 1970. In fact, the argument that Sennawi is putting forward is that Nasser is not even to blame for any of the mistakes of the Free Officers who removed King Farouk on 23 July 1952 and established the republic.

The elimination of political parties, the physical and moral elimination of the opposition, the “firmly unforgivable” violations of human rights, the decline of freedoms of speech and the press, the failed economic plans, the 1956 Tripartite Aggression and the subsequent cracks within the army and the humiliating defeat of 1967 are all someone else’s mistake.

This someone else is sometimes Moahmed Naguib, the military general who agreed to play along with the much younger Free Officers and who soon ended up being under house arrest, Abdel-Hakim Amer, “Nasser’s intellectual twin” and “his first Achilles’ heel”, Anwar El-Sadat, Nasser’s last vice president, “his second Achilles’ heel and his successor who opened the door for the deformation of Nasser’s legacy,” and of course the communists and Muslim Brotherhood leaders.

The defence that Sennawi is making comes from hand-written notes that Nasser, as a younger officer, took down during the 1948 war, other notes that Nasser wrote after the 1952 Revolution, some remarks or statements by Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, the top political journalist of the time and who was incredibly close to Nasser, and an extract from a newspaper story or interview by one politician or another from the times of Nasser.

Nasser’s legacy, Sennawi’s book argues, should be assessed by the ambitious and dedicated political vision that granted this legendary leader his uncontested legitimacy in times of victory as well as in times of defeat. Nasser’s political regime, whatever its flaws, Sennawi writes, cannot be used to assess or judge the legacy of this unusual leader.

Sennawi’s book is loaded with scattered affinity that leaves the reader with a text that is closer to the work of an impressionist – with a definite emphasis on deception of light that creates a picture of a relatively faded scene with no hard angles or definitive lines.

Notwithstanding the fact that it is written by a dedicated Nasserist, who quotes Nasser’s closest associates and even family members, the book is a perfect poetic resume of Nasser’s years – from start to end.

And like the texts of Greek mythology, Akhil Garihan could be read in more ways than one. It could be read as an analysis of the political state of affairs during the 50 years that followed Nasser’s dramatic death in his early 50s while Egypt was still trying to overcome a devastating military defeat that cost it Sinai and cost Palestinians whatever was not occupied by Israel in 1948 from historic Palestine.

Short link: