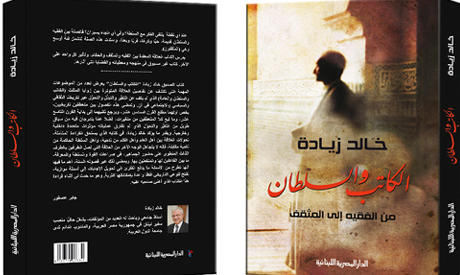

Cover of Khaled Zeyada's 'The Writer and Power'

Al-Katib Wal-Sulta (The Writer and Power), by Khaled Zeyada, Cairo: Al-Masriah Al-Lubnaniah. 2013. 309pp.

In his preface to the second edition of his book, Ambassador Khaled Zeyada marks the 'recent developments' that brought to the surface the debate about the role of the intellectual following the onset of the Arab Spring in 2011.

Zeyada, who released the first edition of the book 12 years ago, says in the new preface that the factors – namely, the Arab Spring – that prompted the intellectuals to resume their role in the political scene, whether through drawing lines to the constitution, participating in the establishment of political parties, or stirring debates around democracy and the civil state, are the very same ones that led to the rise of Islamist political trends and parties to power.

I doubt that the author avoids using the words "revolutions" or "uprising" – opting instead for "developments" to describe the Arab Spring – due to the sensitivity of his position as Lebanon's ambassador to Egypt and its permanent envoy to the Arab League since 1997, but rather because the short preface affords him the chance to relate his analysis of the role of the intellectual across decades to the role of the intellectual in countries of the Arab Spring.

Zeyada believes the Arab world is now entering a new stage of transformation that will spread over a number of years, in which the intellectual, who champions the ideals of modernisation and defends the state, will be engaged in an explicit confrontation of unprecedented magnitude with those who claim to monopolise the correct understanding of religion.

The book is deemed as one of the most important references detailing the tense relation between the writer, power, and the public, through dual historical accounts. The first traces this relation during the beginnings of the 16th century in the aftermath of the Ottoman invasion of the region, and the second during the 19th century after Mohamed Ali Pasha's establishment of the modern state in Egypt.

Through the six chapters of the book, the author concerns himself with deconstructing social phenomena and the ruling apparatus across three centuries, motivated by two questions: the place of Islamic jurisprudence within the state and the birth of a new social character – The Intellectual.

Zeyada sees that the Ottoman rule led to intrinsic changes in the position of Islamic clerics, whom he considers to be the ancestors of the modern intellectual. Those clerics were excluded from governmental posts and toppled from their positions in the monetary and military administrations, the factor that separated religious jurisprudence from the administrative apparatus.

Isolation from politics also stripped religious leaders from their roles as leaders of society, which caused the religious authority to face a real challenge: either transform its role or risk decay.

On the second parallel line of his historical tracing of the creation of the modern Egyptian state, Zeyada uses the word “writer” to refer to those who received a modern education and studied the sciences of their age.

According to Zeyada, for instance, educated people in Egypt were tied to the state and its needs from the start of its creation. And although the relationship between the intellectual and the ruler ran according to the latter's satisfaction, it remained vitally essential, such as the case of Islamic intellectual and scholar Rifaa El-Tahtawy.

The author focuses his analysis on Mohamed Ali Pasha's experience of establishing the modern state in Egypt in the early 19th century. Zeyada believes that Mohamed Ali did not establish a state resembling its counterparts in Europe, but rather a repressive state that seeks to rule society through its military arm. In short, Mohamed Ali’s state did not emerge from society but from outside of it, seeking to control it.

The intellectual who emerged from this society started in service of the state which, in turn, chooses the intellectuals it needs. Intellectuals never really had any independent organisation. The intellectuals, according to Zeyada, lived for centuries waiting for their deserved role, but as soon as these intellectuals became part of the authority, they stopped being intellectuals.

Short link: