If the most famous Arab singer Abdel-Halim Hafez were still alive today (21 June) he would have reached 88 years. He would likely have remained on top of the Arab singing and cinematic scene to this day.

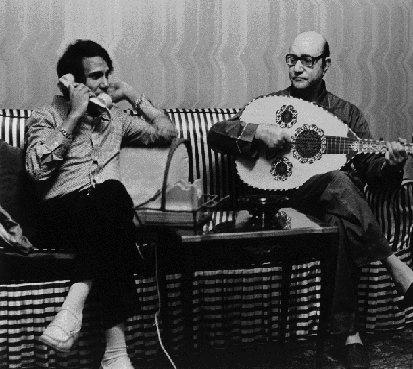

Rarely do performers who reach that age manage to keep their fame and stardom fresh. Yet Abdel-Halim -- who was the most intelligent among his colleagues, and who learned how to hold onto success from his mentor, the musician Mohammed Abdel-Wahab -- would have known how to pour the hardship of his long career into the hearts and ears of his fans.

In spite of his death forty years ago, he was and remains the most important and successful of Arab musicians.

What allowed the "Dark-Skinned Nightingale" - as he was known – to succeed so when he first appeared on the scene, and throughout his career?

Abdel-Halim along with his contemporaries like Mohammed Al-Mougi and Kamal-Al-Taweel, presented Arab audiences with a new and unfamiliar style of music. Initially, listeners neither accepted the young singer nor his style. He was even met with booing and revulsion.

Yet, Abdel-Halim's faith and dedication to his own style quickly began to pay off. He won fans every day as tastes in Egypt changed following the 23 July 1952 Revolution, which synchronized with the emergence of this new voice.

Just as the revolution's success was assured after two or three years, Abdel-Halim became a tangible reality in the music world with songs that began to gain unprecedented popularity. The cinema, which did not welcome him in his early years, preferring to borrow only his voice, was by 1955 asking him to act in major films.

The overwhelming cinematic success Abdel-Halim achieved formed a strong background to his singing success. The opposite was also true. Steadily but surely, this frail young man, who came from deep in the countryside, turned into the idol of the masses and a box-office star. This can be attributed to a number of reasons.

With the success of Abdel-Halim’s first film Our Sweet Days (1955), Egyptian Cinema was liberated from much of its classicism, and pushed in a more youthful direction. Not yet a leading man, Abdel-Halim’s appearance in Our Sweet Days nevertheless helped the film succeed and established the idea of a younger cinema which prevailed afterwards. Likewise his appearance in films like Days and Nights, Girls Nowadays, The Abandoned Pillow, The Sins and My Dad up the Tree.

The emergence of this current heralded the decline of a very formal generation of cinema, exemplified by actors like Emad Hamdy, Yehia Chahine, Mohsen Sarhan.

The new cinema favoured the vividness and fun of youth, who tended to dress casually, riding bicycles or visiting their sweethearts in boats, exactly as Abdel-Halim did in Days and Nights (1955).

1955 witnessed the launch of the romantic film genre in Egypt at the hands of director Ezzel-Dine Zulficar via the film I am Departing this Life. It paved the way for other romantic successes in Among the Ruins, the River of Love and others. Directors like Barakat, who benefitted from Abdel-Halim’s romantic presence Days and Nights, Rendezvous and Girls Nowadays, pushed the genre further.

Once Barakat was assured that audiences would accept these new kinds of films, he began to direct them without Abdel-Halim, as in Until We Meet, Have Pity on My Love and I have Nobody But You. The singer provided Barakat with the audience loyalty he needed to introduce new films and ideas to the scene.

The emergence of Abdel-Halim also allowed filmmakers to imagine casting leading men in melodramatic films – a position formerly dominated by female stars. Singers like Saad Abdel-Wahab, Kamal Hosni or Muharram Fouad soon took the stage, using the tragedies their characters would pass through as opportunities to break into song and subsequently affect the audience.

Prior to 1955, there were also only two people to have achieved what we think of as box-office stardom in the modern sense – that which can make or break films and careers. These two names were Anwar Wagdi and Leila Mourad who ruled the box office from 1945 until 1955. 1955 signalled and end for both.Wagdi died suddenly that year at the peak of his career, even as Mourad retired at the apex of her fame.

But time did not stand still. Abdel-Halim stepped neatly into the limelight, where he would remain throughout his career. The name of Abdel-Halim on any film was enough to drive audiences to the box-office. His films achieved record sales.

Abdel-Halim’s film My Dad up the Tree (1969) still claims the third-longest run time in Egyptian cinema history: it showed for 33 weeks.

My Dad up the Tree is also the only film for which audiences continued to demand repeat screenings thirty years after its release, garnering its production company (Sawt Al-Fenn) profits that surpassed any other Egyptian film. The demand stopped only after the film’s video release and copyrights were sold to one satellite movie channel.

The success of the Dark-Skinned Nightingale’s films also tempted filmmakers to direct remakes of his films after his death, sadly forgetting the most important element of their original success. Remakes of both The Sins (1962) directed by Hassan Al-Imam and Our Sweet Days (1955) by Helmy Halim were made in 1979 and 1980 respectively, but they were a far cry from their originals.

So what is left of Abdel-Halim after all these years?

It is a question that we’ve stood before a long time, since Abdel-Halim’s demise forty years ago, years which have seen massive changes sweep across Arab arts, both in audiences and the creators themselves. Yet the answer is clear; Abdel-Halim remains vital in both spirit, influence and impact. Nobody can fill his place as a singer or even as an actor. What is his secret?

Perhaps the personal factor concerning Abdel-Halim himself has faded with the passage of time that separate us from his demise, for the audience won’t identify themselves with a dead person and won’t remove the existing space between the actor and the character which he plays or the between the singer and the singing situation he is portraying since the artist himself isn’t living in our midst…

Despite having no personal relationship with the new generation, Abdel-Halim retains the capacity to form psychological and human relationship with new generations through his films and the timeless sensitivity of his music.

Many people visit his home and his grave, writing on its walls words of love and longing, even complaints about the problems they face as if he were alive to listen. It is an impact that is quite surprising and deserves to be contemplated and studied; the latent magic of this frail being entrenched in our psyche under the name of Abdel-Halim Hafez.

Objectively, there is also the magic of the black and white, the nostalgia and capacity to address human emotion in ultimate and enduring images. Abdel-Halim’s films were blessed with a formula that combined entertainment and pleasure with high quality technical craftsmanship, compact structure. They made use of Abdel-Halim’s capabilities as a singer, blending his voice seamlessly into the drama, often in ways that surpassed the maturity or grace of other films.

Many directors who collaborated with Abdel-Halim hit highs in their careers at this time as well. Helmy Rafla, for example, engaged Abdel-Halim to produce arguably the best example of musical film in Egyptian Cinema in the The Female Idol.

In this film, you cannot remove a song from its context. At the same time, not a single song delays the action because it is part of, or a comment upon it.

Let us remember the song I Love You, or the dialogue A Strange Thing with Shadia, or the poem You aren’t my Heart, or Without Reproach—each gracefully moving clinching a dramatic moment, transcending the usual pitfalls of musical numbers in film.

For these reasons Abdel-Halim’s films remained the best in the Egyptian musical genre and the most easily restored. Singers who appeared on the silver screen after his death have failed to fill his place, though the form itself is here to stay.

In many modern films, those singers remind us of the Dark-Skinned Nightingale because in most cases they form a shadow of his films or a variation upon them. It is worth noting that the entire body of Abdel-Halim’s work was included in his films, except his patriotic songs and the last emotional ballads he sang in his final years.

Hence, Abdel-Halim was always present in our minds and psyches these long years, expressing a vast range of human emotion on screen and off.

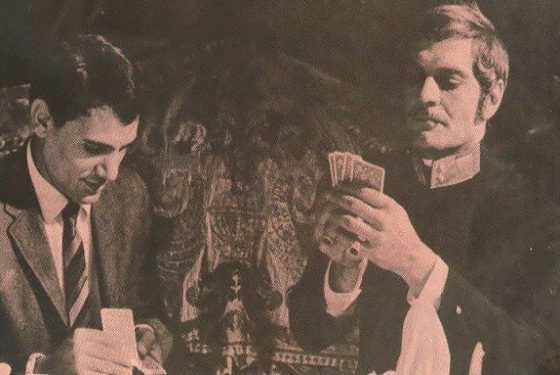

Abdel-Halim Hafez Playing cards with the Egyptian actor Omar Sharif in London.

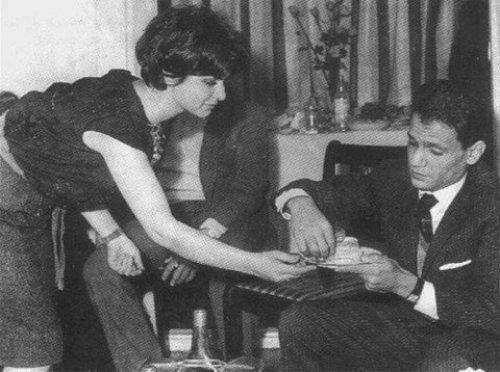

The famous actress and singer Soad Hosni serving a piece of cake to Abdel-Halim.

The singer talking on the phone while the prominent singer and composer Mohamed Abdel-Wahab holds his oud, waiting to start the rehearsal.

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

Short link: