“The heavy velvet curtain closed for the final time. Resounding bravos had died away. The thunder of applause at last subsided. Backstage, exhausted but exhilarated, a gathering of novice ballet dancers thronged around the Minister of Culture. It was the night of 4 December, 1966 at the old Khedivial Opera House, and the premiere of Boris Assafiev’s ballet, Fountain of Bakhchisarai, had just ended.

“Eyes glistening with emotion, Dr Tharwat Okasha announced the attendance of president Gamal Abdel Nasser the following evening. At the performance, the minister had witnessed the first fruits of the ballet school he had founded in 1958, and called during an intermission to invite the president. "This is one of the happiest nights of my life," Dr Okasha declared at the birth of the all-Egyptian Cairo Ballet Company. A photograph in my album preserves that moment.”

Thus Magda Saleh, Egypt’s renowned ballerina, opening “A Ballet for Egypt”, a chapter she wrote as contribution to a book about Egypt’s late first minister of culture, Tharwat Okasha, a collective work based on the memories and experiences of many of those who met or worked with Okasha, translated to Arabic and published by the Kuwaiti Dar Soad Al Sabbah in 1999.

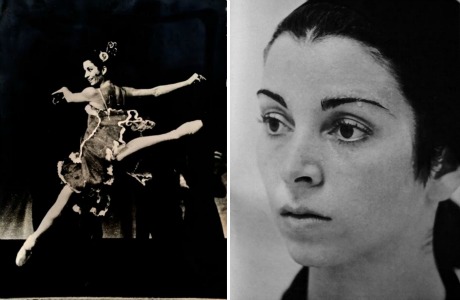

Magda Saleh’s memories are many, and all are interweaved with Egypt’s culture. She made her mark on the stage of the Khedivial Opera (1966-71), and at the Higher Institute of Ballet as a student, professor and dean (1984-86). She was one of the first Egyptian ballerinas to graduate from the Bolshoi Academic Choreographic School, Moscow (1965), and she briefly served as the founding director of the new Cairo Opera House Cairo (1987-88). Since 1992, she has lived in New York, where she has nevertheless not detached herself from her home country.

Though decades have passed since Saleh left, in which Egyptian culture went through all kinds of transformations, Saleh’s name returns in the conversation of those who worked with her, those who remember her breathtaking performances and those who, decades later, recognise the efforts she made for Egyptian culture. As Saleh’s legacy continues, in the next few months we will be able to revisit her career and Egypt’s cultural history through a A Footnote in Ballet History, a documentary in production by Hisham Abdel-Khalek. But first – or, let’s say, at the same time – let us draw a step closer to Egypt’s prima ballerina and the cultural history she represents.

Magda Saleh (Photo: courtesy of Magda Saleh)

The star is born

Saleh was born to an Egyptian father and a Scottish mother. “My father, Ahmed Abdel Ghaffar Saleh, was a distinguished academician, a pioneer of agricultural education in Egypt. He held many key positions across a number of universities, and finally he was a Vice President of the American University in Cairo [1965-1974]. I was the second of four children and the only daughter,” Saleh begins, swiftly adding how her three brothers always treated her as “one of the guys. It was a privileged position in a sense.”

Saleh expressed an interest in ballet when she was very small. Her father had just been transferred to Alexandria, so she enrolled in the Alexandria Conservatory, which had a ballet section. “At that time,” she recalls, “it was a very important conservatory for the instruction of music. They were very enlightened and had a ballet department run by a British lady from the Royal Academy of Dance.” Saleh’s talent caught the instructor’s eye, and she was sent on a scholarship at the Arts Educational School, Tring, Hertfordshire, UK. But a mere two months into her experience abroad, the Suez Crisis broke out (1956) and all Egyptians had to be repatriated.

At the same time, to parallel that expulsion, the British ballet instructor was sent back to her home country and her place was filled with a local, Italian ballet teacher. As the ties with the Soviet authorities deepened, in 1957, the Alexandria theatre received a visit by the world famous Moiseyev Dance Company (Theatre of Folk Art). Igor Alexandrovich Moiseyev, the director of the company, visited the ballet class at the conservatory and was impressed with Saleh’s skill.

In this memorable encounter, Moiseyev told Saleh that the following year a teacher from the Bolshoi would come to Cairo to open a school and suggested that she should audition. The young ballerina followed Moiseyev’s advice and, a year later, she was accepted along with 30 boys and girls. This historical audition planted the first seed of what would soon become Egypt’s iconic ballet talents. As the school was expanding, more teachers from the Soviet Union -- from the Leningrad’s Kirov (Mariinsky) or Moscow’s Bolshoi ballet academies -- were joining the academic forces.

“Curiously the two camps were big rivals in their home country, yet they came together in Egypt and gave us the best of their schools,” Saleh proudly recalls the days when those masters provided her formative experience – and how strong they made her.

With Diana Hakak, Maya Selim, Aleya Abdel Razek and Wadoud Faizi, Saleh was among the first five girls to be sent to Moscow for further training where they spent two years at the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, graduating in 1965. Shortly afterwards, in 1966, that same group gave the inaugural performance of the Cairo Ballet Company, the Fountain of Bakhchisarai where Saleh played Maria in among a cast made up entirely of students of Cairo’s ballet school. The ballet was directed by choreographer Leonid Labrovsky, former artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, with the Cairo Symphony Orchestra conducted by Shaaban Abou Saad.

Saleh recalls the event was “a bombshell, in a good sense of the word”. The principal dancers were honoured by the state’s order of merit. “It was an incredible event in the history of culture and the arts. Back then, Enayat Azmi, the dean of the ballet institute and head of the growing company, said, ‘Enjoy it, this is the first and last time we will get anything,’ which was very true. Still, it was all very promising and a revelation for the Egyptian theatre” when Fountain of Bakhchisarai embarked on “a great adventure” and travelled to Aswan. It was a resounding success.

“I may be Egypt’s first prima ballerina, but we must not forget that I did not do it on my own. There were many great people involved in creating me and the first to be mentioned will always be Dr Tharwat Okasha. He had an enlightened approach to culture, and knew how to face serious opposition in creating a state-sponsored dance school,” Saleh says, explaining the stigma attached to the dancers in a conservative society.

But while her career was taking a serious turn, Saleh’s father himself was concerned about her. “Though my father was a very enlightened man, he said to me, ‘Allowing you to be a professional ballet dancer entails for me a grave social risk.’ He was also aware that ballet is a high risk career and that any injury could terminate it. Giving me his blessing must have been a difficult decision, socially speaking. But luckily, the years have shown that the Egyptian people made an exception in our [the ballet dancers] case because the ballet was high culture, a glamorous and involved complex foreign art form, and you know how we admire foreign imports,” Saleh comments.

Soon, the worries of Saleh’s father were taken over by an immense pride as, increasingly, he was congratulated on his daughter’s performance. “My father often joked that his social status was changed from Dr Abdel Ghaffar to the father of a prima ballerina Magda Saleh.” Paralleling her ballet career, Saleh also studied at the English Language and Literature Department at Cairo’s Ain Shams University (graduating in 1968 with high honours).

The following years developed a large audience for the ballet performances, which were always sold out in advance. The success only boosted Okasha’s dream. He decided to establish workshops for scenography, prop and costume design and construction, alongside the ballet shoemaking, all led by Soviet specialists. “Ballet shoes were always our major concern. We had to depend on the visiting companies to give us their leftover and used shoes so we could perform,” Saleh clarifies.

Khedivial Opera House or Royal Opera House (Egypt's old opera house) burned down on 28 October 1971. (Photo: Al Ahram)

While the Soviet teachers kept adding new ballets to the repertoire, in 1967 the first class to complete the nine-year programme graduated. This included the leading male dancers – Reda Sheta, Abdel Moneim Kamel (Mike), Reda Farid, Ahmed Shoukri and Tarik Saleh (Saleh’s younger brother) – as well as soloist ballerinas Hanzada Faizi, Nadia Habib, Mary Abdel Malek and others. Thereafter, incrementally, the graduates would yearly join the company.

Yet, apart from the sparkling stage lights and the never-ending applause, 1967 also brought about worries, especially for the male dancers, as political tensions culminated in the Six-Day War. Drafting male dancers into the army would end their careers. In 1968, the company premiered Giselle, one of the greatest classical ballets, and Saleh’s favourite role, “but isn’t it a dream come true for every ballerina?” she comments.

Okasha managed to keep the ballet going against the odds, notably between 1967-71, when the company’s other major works included The Nutcracker, Don Juan, Daphnis and Chloe, Paquita Variations and Don Quixote.

“Don Juan was spectacular and so lavish in its Renaissance costumes that the audience would applaud when the curtain opened, especially to a grand ballroom scene,” Saleh recalls. “It was then that my partner Reda Sheta -- the first Egyptian male dancer to have a high-profile career in Europe -- was replaced by Mike, with whom I danced the following ballets. In May 1971, I danced Kitri in Don Quixote, the last ballet staged before the opera burnt down in October that year.”

Saleh adds that one of Don Quixote performances was attended by the deputy Soviet Minister of Culture who believed the dancers were worthy material for the renowned Bolshoi, “the greatest dance company in the world. Soon after, together with Mike, Saleh danced on the Bolshoi stage, first in the company’s production of Don Quixote then in Giselle. “Those were my final performances as ballerina. This was the great culmination of my on-stage career, and the highest point of the Egyptian ballet as represented by Mike and myself,” Saleh asserts.

The day that changed everything

On 28 October 1971, at the peak of her successes, the tragic news shook her together with the rest of culture scene. She still recalls that day with deep sadness.

“I was at the institute in Giza when Hassan Sheta, Reda Sheta’s brother and a talented dancer in his own right, rolled up on his motorcycle and said the opera house was burning. We immediately went to Abdin. As we approached the Opera Square, we saw the immense crowd of people, all silent, shocked. Even in telling you this now, I am shaken; it is very hard to relive. The flames were coming out of the roof... I saw maybe two or three fire trucks with fire hoses; some people said there was not enough water pressure and it was a wooden building... The whole crowd of artists, opera singers, musicians, dancers, actors, the workmen, everybody attached to the opera and arts, we all stood there and wept.”

New Cairo Opera House, launched in 1988 (Photo: Ati Metwaly)

Saleh goes on to explain that while the tragedy has remained a mystery and the truth can no longer be recovered, the fact of the opera’s burning affected many aspects of life in Egypt, going far beyond art and culture. “My mother suggested that I should look for an alternative path, such as academic development. I had to put my prima ballerina career to one side and reinvent myself as a student. While many of my colleagues departed to Moscow to continue their graduate studies, I obtained a scholarship to study Modern Dance Techniques and Choreography at the University of California at Los Angeles. Of course I hadn’t had a faintest idea of what modern dance was as we hadn’t really had a chance to see it in Egypt.”

Saleh obtained a master’s degree with her thesis, “An exploration, in modern idiom, of Egyptian themes”, in which she created choreography based on the ancient Egyptian legend of Isis and Osiris (1974). Further on, she completed her PhD, entitled “A Documentation of the Ethnic Dance Traditions of the Arab Republic of Egypt” at New York University (1979). The work was accompanied with an audio-visual component, a feature length film titled Egypt Dances, and ethnographic documentation of the wealth of Egypt’s dance traditions with 17 samples of folk movements from various cultural areas.

In the meantime, in Egypt, with all former stars either in the Soviet Union or other corners of the world, the ballet company was floundering within the Academy’s halls, adjacent to the Sayed Darwish, Balloon and Gomhoreya theatres – it’s glimmer fading in anticipation of the company dying the predictable natural death. Saleh came back and was appointed professor at the Ballet Institute, Academy of Arts by director Samha El-Kholy. Around the same time, a few other ballet talents made their way back, among them Abdel Moneim Kamel who dedicated himself to creating a ballet company from scratch.

“Unfortunately by the time we came back, everything has been literally destroyed. What was happening in the institute only mirrored what was happening in Egypt, a downward spiral. The beautiful institute that I was educated in and graduated from, the pride of the Ministry of Culture, was hardly a shadow of what it used to be.”

Saleh calls this period “the most unhappy time of my life,” made all the more difficult by her parents’ deteriorating health. Naturally, she had to divide her time between trying to restore her dream and her ailing parents. “It was a very sad time coupled with a lot of opposition in the cultural field. I could not deal with all the obstacles. The strain of the job of fighting to restore the institute and the care for my parents brought me to near-collapse. I resigned from my position as ballet institute dean and professor.”

In 1987, even before Farouk Hosni’s appointment as Minister of Culture, Saleh got closer to the new project that was the new Cairo Opera House.

“I was involved in social and diplomatic circles in Cairo and I was already known among the Japanese teams. During one of the gatherings I met the Japanese Ambassador, with whom I had a casual chat about the special requirements that any theatre needs to meet in order to accommodate ballet performances. One day later I was contacted by the major architect of the Cairo edifice,” Saleh recalls pointing to the many plans of the new Cairo Opera which as she noticed still lacked essentials needed for the ballet troupe.

Hosni was appointed minister in October 1987 and contacted Saleh offering her directorship of the new building under construction and promising to support her all the way through.

Magda Saleh with husband Jack Josephson, the renowned art historian and authority on ancient Egyptian sculptures. (Photo: courtesy of Magda Saleh)

Hopes and disappointments

Becoming the founding director, Saleh began official meetings with the Japanese team working on the opera which “though it involved a series of challenges and hardships was one of the most wonderful professional experiences in my life. You do not go and have an opera house dumped in your lap and told to get on with it.” Saleh explains that the Japanese were building this opera for three whole years with a purpose of creating “the Culture and Education Centre, a multipurpose facility rather than an opera house in the precise meaning of the word.”

As she began communicating with the responsible teams, she started discovering that the Japanese team had tons of plans and files, “topped with three years’ worth of letters addressed to the Egyptian Ministry of Culture, none of which was granted a single answer. Moreover, I learnt that there was no provision made in a ministry’s budget for the new building about to be inaugurated. I had to get creative. I prepared an outline for a grandiose inaugural event and laid plans for the first season, to which I invited all Egyptian companies to give their ideas. I wanted also to include Egypt’s traditional music, beyond Arabic and folklore.”

Saleh also hoped to keep the opera as a "quasi-independent entity i.e. a general organization having the greatest degree possible autonomy within the ministry," an idea she was told could be pursued at a later stage.

Saleh says she managed to secure a lot of funds, had clear artistic expectations laid down and was on top of all the functions of the building, from air conditioning to plumbing. In the meantime she received a lot of support and respect from the diplomatic circles. “I worked like a madwoman but I worked in a vacuum. Despite Hosni’s promises, I had no support from the ministry and slowly but surely, the intrigues started making their way in.”

Saleh continues to say that while the Japanese team glorified her efforts, the obstacles or lack of support she experienced from ministerial parties, with Hosni on top of the list, made it hard for her to pursue anything the way she imagined.

“At the peak of those struggles, Ratiba El-Hefny [soprano, professor and former dean of Institute of Music at the Academy of the Arts] was brought to the Cairo Opera and placed hierarchically as my superior, making her the opera’s chairperson. Of course, I was expected to resign which I decided not to do. A minor internal clash over something was enough to add insult to injury. I was officially fired from the opera and I found my office sealed,” Saleh recalls, calling this fact “shocking, punitive behaviour”. Saleh adds that she filed a lawsuit which, many years later,when she was already a permanent resident of the United States of America, she won.

Following her bitter experience at the opera, Saleh returned to the Academy of Arts where she stayed for a year before asking for a sabbatical so she could go to the United States, invited as a visiting professor at New York University’s department of dance. She stayed at the university for one year, and during that time she met Jack Josephson, the renowned art historian and authority on ancient Egyptian sculptures. “In fact we already knew each other from previous years, our paths had crossed several times.” One thing led to another and their relationship turned to marriage.

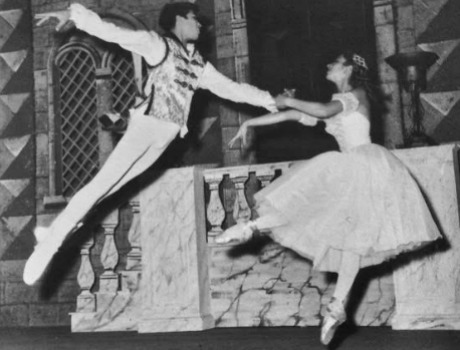

The Fountain of Bakhtchisarai Act III: Maria (Magda Saleh) resists Khan Girei (Reda Farid - still a student at the Higher Institute of Ballet) - Old Cairo Opera House December 1966. (Photo: Leonid Jdanov, courtesy of Magda Saleh)

"Egypt within me"

In the meanwhile, Saleh remained active in Egypt's culture. "I succeeded in organizing a visit to the Cairo Opera of two events: The Joffrey Ballet of Chicago and the New York based Noche Flamenco. Under the auspices of Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism, she organised and coordinated a 12 performance engagement of the Bolshoi Theatre Grigorovich Ballet, at the Cairo International Convention Centre, an event that drew a total of 33 thousand spectators, marking the launch of the centre as a theatrical venue.

Even when in 1992, Saleh has made New York her home, she maintained close links with Egypt, either through tours with friends or by pursuing further cultural cooperations.

In New York, Saleh established good a connection with the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts at the Lincoln Center. “Together with my good friend, Nimet Habachy, a programme presenter on a classical music station in New York, and Mona Mikhail, a professor in NYU and AUC, along bass-baritone Ashraf Sewailam and baritone Raouf Zaidan, we were granted space to make presentations about Egyptian culture and arts. In fact, Sewailam, Zaidan and Kamel Boutros gave presentations of opera in Arabic. It was very popular. We also presented films, organised talks about the Egyptian dance, ballet, theatre, music. I gave several lectures, etc. We also managed to organise recitals of Egyptian musicians such as pianist Mohamed Shams, French horn player Amr Selim and his wife pianist Seba Ali, among others,” Saleh enumerates, calling those efforts very modest and hoping that similar efforts will be made by Egypt’s official bodies.

“On the one hand we have all this: the Ministry of Culture and the Academy of Arts. And on the other hand we have embassies of foreign countries which over the years have proved very active in bringing their culture to Egypt. It is natural to expect reciprocity. But for some reason, Egypt does not make efforts to promote the many young talents it has. I saw so many talents wasted, and only some of them manage to run away and make their careers by themselves.”

Officially retired since 1993, Saleh enjoys doing “small things for Egypt in New York”. Today she looks at her life with a sense of accomplishment.

“It was a special confluence of time, place and circumstance that made this possible. A career like that would be possible neither earlier nor later and I was very lucky in this respect. In a sense, I have a good life and I am blessed. My career as a dancer was very brief, followed by dynamic academic development. Things didn’t necessarily go the way I foresaw them but this is how it happens in life. Despite all the obstacles I experienced at the Academy and the new Cairo Opera, my intention was always to give back to Egypt even if the circumstances didn’t always make that possible. Though I might not be physically in Egypt, wherever I go, Egypt is certainly within me. Maybe it is a romantic way of looking at things,” Saleh says. “But it keeps me going.”

December 1966 dress rehearsal of The Fountain of Bakhtchisarai, Act I. Magda Saleh as Maria and Reda Sheta as Vaclav (Photo: courtesy of Magda Saleh)

This article was first published in Al Ahram Weekly

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

Short link: