“It must have been a year or two after the war came to an end. I was walking on Safiya Zaghloul Street in Alexandria when I saw posters for the films showing that summer, many of them documenting the October War, one of the finest moments in the nation’s history.

“I could not help my tears when I remembered the war, especially the heroism of the soldiers, officers, reservists or conscripts, who had gone to the front from across the country,” said Nubian writer Haggag Odoul, a soldier in the October War.

Odoul does not feel that the various cinema productions over the years have given enough credit to “the bravery and excellence” that the soldiers and the entire nation showed on the road to the October War and during the conflict itself, starting on 6 October and ending on 28 October 1973. However, moments like at the Kabrit fortifications, where Israel had encircled members of Battalion 603 for close to four consecutive months, had been well represented, he said.

“There is so much to be said about the war, about the days after the defeat of 1967, the relentless march of the army towards a new war to liberate the land that had been occupied by Israel, the many individual contributions of extraordinary men like Baki Youssef, an engineering officer who proposed using water blasts to create holes in the Bar Lev Line, and Ahmed Idris, a Nubian soldier who proposed Nubian as a code language for the operations, and many others,” Odoul said.

“But above all we need to give credit to the incredible assembly of talents that unconditionally poured out of every soldier and every citizen to make the days from 6 to 28 October days of honour for a nation that had seen the agony of defeat in 1967,” he added.

“The road back from the battlefields came after really difficult times when we were encircled by the Israeli army beyond 28 October,” recalled Mohsen Fawzi, a retired army officer.

Fawzi was a member of the Third Army battalion that had had to survive for weeks with little food and hardly any water until the end of January 1974 when its members were allowed to start coming back home after the beginning of talks between the leaders of Egypt and Israel under the auspices of the UN and with the direct intervention of the US.

However, Fawzi’s captivity in the wake of the Israeli breach that started on 16 October and managed to take the Israeli army, which had sustained severe losses, from the eastern to the western bank of the Suez Canal, brought him none of the pain and agony that he had had to go through on his way back from the 1967 War.

“There was a big difference: in 1967, we were coming back in total disarray. We were just walking back almost aimlessly through the desert from the west bank of the Suez Canal after Israel had completely paralysed our aviation. We were walking back in hundreds or maybe thousands and did not know if we were going to survive the desert, the acute thirst and hunger, and the sporadic attacks from Israeli aviation,” Fawzi recalled, his face showing the pain of recollection.

During the weeks of isolation after the end of hostilities in October 1973, Fawzi had had no doubt that he might die, as he might have done in 1967. But this time round, he would not have minded death, even though he was yearning to come back to his family and to his young son Tamer.

“It was different in 1973 because we had fought like heroes should fight. We had crossed the Suez Canal and challenged the myths of the ‘unbeatable’ Israeli army and the ‘invincible’ Bar Lev Line. It would have been a worthwhile death,” he said.

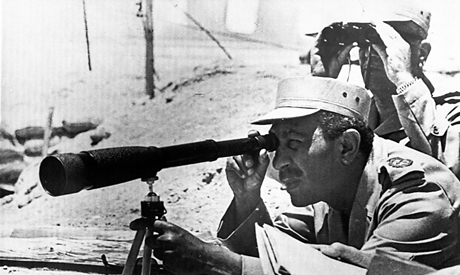

Sadat assessing the situation during the war

During these weeks between 28 October 1973 and 31 January 1974 when the return of the soldiers started, Fawzi’s young wife Mushira, was “scared to death about the fate of her husband.” She had married Fawzi two years before the war when neither thought conflict was coming.

There was of course the War of Attrition, and there were martyrs coming back from the war. There was the big day when the nation paid its respects to Abdel-Moneim Riad, Egypt’s chief of staff who died on 8 March 1969 during the military operations that followed the 1967 defeat. But neither thought there was going to be another war to reverse the defeat.

“I don’t know why: maybe because the defeat had been so painful, and maybe because when [former president Gamal] Abdel-Nasser died in September 1970 we thought it was all over,” Mushira said.

Fawzi kept going and coming from the front, and Mushira would be reassured every time he called to say he was coming back. The one time when she was alerted by his unusual request to send winter clothing with a messenger from the army in the early days of October she thought was “just part of a long drill he was involved in”.

It was in the early afternoon of 6 October that Mushira learned from the radio that the war had started. Like the spouses of other soldiers in the battlefield, Mushira had moments of mixed feelings — “the confusion of having him in the middle of the war and of thinking we are crossing the [Suez Canal] and we might win, or then again we might lose and go through a more painful defeat,” she said.

When “it was all over” and Fawzi had found his way back to his parents’ house in February 1974, he knew that he had not just survived death one more time, but that he had also survived the humiliation that he and other soldiers had had to go through after the defeat of 1967.

When Fawzi came back to his parents, his spouse and his young son, he knew he would not have to hide while walking down the street, or fear to wear his military uniform, or try to avoid making noise while taking the stairs up to his apartment. He knew he would not have to look down when his mother opened the door to him or sob at “an unfair defeat imposed on the army that never had the chance to fight in 1967 but was willing to fight despite the damage imposed on the air force”.

“I was coming back a proud soldier who had fought bravely and honourably, not as a soldier who had not had the chance to fight and who had had to obey the orders to come back in a disorderly retreat, with soldiers dying around me,” he said.

‘WE WANTED TO KEEP ON FIGHTING’: Raafat Al-Shimi was a reserve officer in the October War. Only one year before, he had graduated from university and joined the Reserve Officers Academy and graduated just months before the war started.

“It was the spirit of the time: as young men, we felt an incredible sense of humiliation after the 1967 defeat; we felt broken, and we wanted to fight and free the land that Israel had occupied,” Al-Shimi said.

But despite this “urge to undo the defeat” that Al-Shimi and his colleagues felt, there was also the uncertainty that was holding many hostage. “We thought we would have to fight, and the political leadership was promising it. We were training for it, but deep down we feared it might not happen. However, when it happened, we knew that no matter the sacrifices and no matter the difficulties, we could win, no matter how many days or weeks we had to fight and how many lives we had to give,” Al-Shimi said.

Just a few days before the war, he was sent on leave back home. “It was my first day back home after 12 weeks of intensive training. I was going home thinking that I was going back to the training, but when I was leaving the house my sister stopped me at the door to give me an apple to eat on the way back. For some obscure reason, I thought that it might not be soon that I would come back home again and see my sister and family again,” he recalled.

This was on Thursday 4 October 1973. Two days later, Al-Shimi was in the middle of a war that lasted over six weeks. The first time he heard there was going to be a ceasefire was on 22 October, but it was only on 28 October that the guns were silent. On 22 October, UN Security Council Resolution 338 called for a ceasefire within 12 hours, but the call was not honoured as Israel had moved closer to the city of Suez.

On 23 October, the Security Council reiterated its call for a ceasefire and issued Resolution 339, but again Israel shrugged off the call. On 24 October, Israel completed its encirclement of the Third Army and the city of Suez, though this fought back bravely for two consecutive days and forced the Israeli army out.

On 28 October, Egyptian and Israeli military leaders met at the Kilometre 101 marker to agree on the details and implementation of a ceasefire that went into effect this time round.

“It was a moment of mixed feelings when the word came out that the ceasefire was on, because we knew that the issue of the Israeli breach was not settled and that we had soldiers who were encircled. We knew we could still fight on. We wanted to keep on fighting until we had liberated all of our land, but the decision was in the hands of the political leadership,” Al-Shimi said.

“Nobody wants a war; nobody wants death and pain; from 6 until 28 October we lost soldiers and we looked death in the eye many times. But we had no choice: we had to regain our land, and we had to regain the reputation of our country and our Armed Forces. I think we did this,” he added.

Eight weeks after the ceasefire, Al-Shimi was finding his way back to Cairo. He was travelling through Ismailia as he had done on the way to the front and later. This time, though, while he saw the damaged houses and empty streets of a city that had been almost deserted after the 1967 defeat, Al-Shimi thought that life was bound to come back to this city and to all the cities on the two sides of the Suez Canal that had been deserted after the 1967 defeat.

“I thought we had gone through much sorrow, and it was time for us to rejoice,” he said.

Medhat Mohieddin, a conscript who had joined the army in 1969 and was a member of the 603 Battalion that was encircled for 114 days by Israel at the Kabrit point, was as proud as Al-Shimi when returning from the front to Alexandria in February 1974, especially as for him 28 October 1973 did not bring the end of hostilities. “The Israelis under the eyes of the world continued their encirclement and continued to deny supplies to the members of battalions who were losing their lives due to a lack of food, water and medication,” he said.

Mohieddin was also eager to “get back home and to see the family that was not sure about the fate” of their son at the front. “I cannot say that I was not happy to be going back, and I cannot say that I was not happy to be hailed by everyone who saw me and who saluted me as a hero,” Mohieddin said.

However, at the same time he “was not sure if a ceasefire was what we should be opting for at that point of time. I kept thinking that for all those officers and soldiers who had given their lives to liberate the land without thinking twice about it, and for all those women who had lost their husbands, sons and fathers, maybe we should keep on fighting to have a better victory than the one we had,” he said.

“But I understand that there is no war without an end, and I understand that there is no perfect military victory,” he added.

DOCTORS ALONGSIDE SOLDIERS: Samir Hanna was a newly graduated dentist when he joined the Armed Forces to do his four-year military service as an officer in 1972.

Like all young men at the time, Hanna knew when his military service would start, but he was not sure when it would end, “because even though we talked about going to war to liberate our land, and even though [former president Anwar] Al-Sadat since he took office [in October 1970] had kept promising war, and even though there were demonstrations by students calling for war, I am not sure we believed the day would come,” he said.

In the first week of October 1973, Hanna was going back to his post in Ismailia from a short holiday, and it was then that he really thought that “something was about to happen. There were so many soldiers being summoned back, and it looked to me when I arrived from Cairo that many reservists were being summoned,” he recalled.

From the day he got to his post, only three days before the beginning of the war at 2 pm on 6 October, until the day the war stopped on 7 pm on 28 October, Hanna saw “incredible stories of bravery — something really beyond words”.

“It was a moment of absolute self-denial: nobody was thinking of anything but victory. I could talk for hours about the soldiers — conscripts and officers and often-forgotten doctors at the front who also gave their lives while trying to save the lives of soldiers under Israeli fire,” Hanna recalled.

For three weeks, Hanna himself was in charge of transporting wounded soldiers who had received basic treatment that would sustain them on the 40km trip to the nearest hospital where they would be either treated or sent back home or to the military hospital in Maadi for further medical help.

“We were there for a war that we never knew when it would start and when or how it would end, and we knew that despite the glorious moment of the crossing that the Egyptian army had secured that Israel was set to fight back ferociously,” he said.

On 16 October, Hanna received the disturbing news of the Israeli breach in a coded cable from the military command. “I will never forget the words I read on that day: stick to your post until death comes for you.” This, he said, was what every single soldier and every single doctor at the front was willing to do. “We would not have accepted to come back defeated — we would have rather died,” he said.

Hanna knew that when the ceasefire was reached on 28 October, the impact of the breach was somehow contained either by political or military means.

Nabil Meheri, at the time a young surgeon, was on duty at the Suez Public Hospital during the war. He, along with 15 other doctors, was summoned by the ministry of health as the Israeli breach was taking place.

“It was a very challenging moment for everyone, and clearly all those wounded soldiers we had come to help knew what the breach meant. It was simply amazing what I saw: I am talking about soldiers who were brought from the front with severe wounds who just wanted to get up on their feet and go back again. I am talking about soldiers who had undergone major surgery and who were practically unable to stand who just wanted to go back to fight,” Meheri recalled.

These scenes of incredible bravery did not stop “for a single day” from 16 October until 28 October when the ceasefire was announced.

Judging by the situation at the hospital, Meheri thought on 28 October that huge numbers of sacrifices had already been made. “There were many young conscripts and officers who were very young and who sustained major and at times crippling wounds. Some lived and some died. We were not sure about the numbers of the wounded and martyrs, but we knew that the sacrifices were huge,” he added.

But what Meheri saw on that day was an ongoing sense of vigilance and combat-readiness. “The soldiers were often heavily wounded, but their morale was very high. Even those who were transferred to the hospital after 28 October — they too were ready to go back to the front if summoned. It was very moving, but war is a horrible thing and it should never go on unduly,” Meheri said.

It took Hanna and Meheri a few weeks after the ceasefire to go back home to their families who had heard little of them during the weeks of the war and who continued to fear for their lives even after the ceasefire.

Just like the soldiers who were given an incredible salute upon their return, so were the doctors, saluted by a nation that had feared that it would be almost impossible to overcome the defeat and humiliation of 1967.

THE IMAGE OF THE ARMY: Ahmed Rashed and Magda Adli were in their last and first years at the faculties of medicine at Ain Shams and Cairo universities when the war started.

They were at the hospitals of their universities to assist the doctors and nurses in looking after wounded soldiers when the ceasefire was announced. It took each of them a moment to react.

Adli, politically active since her younger years, “was in a state of shock and dismay. I knew that the war was not over and that for us to agree to a ceasefire when the situation on the ground was not fully in our favour was a mistake. I was young, and I was thinking that we would be able not just to liberate all of the Egyptian land that had been taken by Israeli military force in 1967, but also all of Palestine,” she recalled.

With this mindset and with many of the wounded soldiers in the ward, she was “devastated, absolutely in tears and pain”, at the announcement of the ceasefire. But at that moment she did not have time to let go of her grief over what she thought of as “a political miscalculation by Sadat that would come at the price of the sacrifices that the army and the whole country had made to make this war of liberation come true”.

Rashed, “heart and soul broken by the 1967 defeat and demoralised by the death of Nasser and sceptical about the ability or willingness of Sadat to go to war,” saw things differently.

He was unsure about the political and military significance of the ceasefire coming back to back with the Israeli breach, and he was faced by wounded soldiers who were still willing to fight if they had to. Proud as he was of the army that he had felt sorry for in 1967, Rashed was willing to give Sadat the benefit of the doubt.

“I cannot say I was immediately happy with the ceasefire decision given the situation on the ground, and I was opposed to Sadat and never thought he would actually go to war even a few days before 6 October when I saw soldiers being transferred by military train and big hospitals being taken over by the military. However, I cannot say I was immediately opposed to the ceasefire either, because despite a moment of confusion I was willing to think that Sadat might have a plan in mind one more time,” Rashed said.

The transformation of Sadat from being widely seen as a weak political leader who had come to power in the wake of the sudden death of Nasser, and of that of the army, whose image in the eyes of the nation had sustained huge damage after the defeat of 1967, was one of the biggest things Rashed took away from the 1973 War, delaying his final exams and consequently his graduation for a little under a year.

For Adli, the October War did not bring about a long-lasting transformation in Sadat, but it did “replace the sentiment of anger towards the army after 1967 with contentment. We could debate for years to come about what made Sadat decide to go for the ceasefire on 28 October, and we could speculate about the positions of his top military aides and try to dig into their testimonies about the time, but we have to say that even if the victory was not as big as we wanted it to be, it was a victory and a moment when the nation parted ways with despair. For this, the soldiers at the front have to be credited,” Adli said.

The ceasefire of 28 October and the subsequent agreement of 18 January 1974 were the “inevitable preludes” to Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem later, which she wholeheartedly opposed. For Rashed, the ceasefire was “the beginning of the end of the sense of political meaninglessness that had taken over an entire generation after the 1967 defeat.”

According to Odoul, 28 October was perhaps the day when the nation stopped celebrating the sacrifices of its great army and tried to get back on its feet.

“There are many things that I keep thinking of every year in the month of October. I think of the war and of the soldiers who went and never came back. I think of 1967 and the pain of the time, and I think of the beautiful patriotic songs that came at the time, especially ‘we are going with arms in our hands, and we came back carrying victory flags in our hands,’” said Nadia Ahmed, a retired civil servant.

Throughout the war, Ahmed joined other university students to visit wounded soldiers and bring them gifts and carry messages to their loved ones. For her, the days from 6 to 28 October “will always be the most unforgettable days of my life that I will always remember in the echoes of this beautiful song,” she said.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 31 October, 2019 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

Short link: