In his old-fashioned Heliopolis grocery store, Hussein is finishing his late morning to early afternoon shift.

He is picking a few things to take home to his youngest grandchild Ahmed, selecting two dark blue milk chocolate bars, one golden wrapped chocolate biscuit, and one blue-and-white caramel paste milk chocolate bar. They are all products of the Corona confectionery company.

“Ahmed is the only one of my seven grandchildren who has developed a liking for Corona. I brought him a box of the extra milk bars for his third birthday last year. He loved them and would not settle for any other taste now,” Hussein said.

Having owned this small grocery store for well over 50 years, Hussein had also had his own time with Corona. In the early 1960s when he started his business, it was essentially Corona and another Egyptian chocolate brand Ika that were bestsellers.

“Back then, there were not so many brands as today. There were only a very few brands that offered a wide range of chocolate, biscuits, candies and bonbons. A child would come in and get two and half piastres out of his pocket, and I would know immediately that he wanted the hazelnut Corona, the one that used to be wrapped in red and yellow,” Hussein recalled.

This scene ended, Hussein added, in the 1980s when new brands came onto the market. By that time, Corona, its sister confectionery producer Nadler, which used to supply bonbons and jelly powders, and Ika, were all losing space to newcomers.

Hussein stopped getting supplies from the company because they were not selling well, “except for Rocket”, the caramel paste chocolate bar. “It did not have the same constancy, but it was still popular. People loved it for its chewing experience,” Hussein laughed.

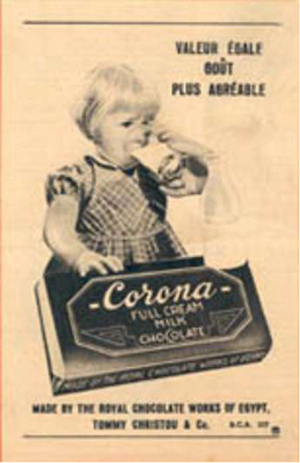

Rocket was not the first product of Corona when Greek confectionery maker Tommy Christo started his company in Ismailia in 1919. The small full-cream chocolate bar in its dark blue wrapping was the first product. Rocket came along a few years later when Christo took his business to Alexandria and started to produce more and use more recipes.

According to Omar Taher in his book Saniyaait Masr (Artisans of Egypt), Christo was sensitive to the idea that chocolate should bring happiness, and that if workers in a chocolate factory were not in a good mood they could pass on their sombre vibes to the chocolate they were producing.

To help Corona’s workers stay in a good mood, Taher wrote, Christo decided to build a football pitch for workers so they could have recreation breaks. One day, a deer was seen running about the pitch, and it was then that Christo decided to make a deer the trademark of his confectioneries.

Later on, when Christo’s company merged with Nadler, owned by businessman Maurice Nadler, both companies kept the deer trademark.

In the 1960s, Corona and Nadler were nationalised, to the dismay of their owners. According to Taher, with the continued presence of a leading team member, the brand survived for a little under two decades more before the market was taken over by the more serious competition that came with the open-door economic policy of the mid-1970s.

Then came a lull that was followed by the privatisation of the company to Egyptian entrepreneur Sami Saad a little over a decade ago.

According to Ahmed Al-Nadri, a marketing manager at Corona, the strategy of the new management was based on bringing back the brand as “the taste of Egypt. We started to work on bringing back Corona as the chocolate of Egypt,” Al-Nadri said.

Corona chocolate bar

MAKING A COMEBACK: Three years ago, things started to change, Hussein argued. “The company was approaching us to go back to distributing its products. It said that the quality was improving,” Hussein recalled.

Hussein was reluctant, however. “It was after the devaluation of the pound, and everything was getting more expensive. People had already started to cut down on buying non-essentials, chocolate and candies included,” he said.

Already seeing a reduction in sales of the popular international brands that had started taking over the Egyptian market by the late 1990s, Hussein would only bow to a box of each of the re-incarnated products: Bimbo, the chocolate-coated biscuits, Rocket, an all-time favourite, and a butter chocolate bar in turquoise blue wrapping.

“It was nice, I must say, at my age to see the deer trademark back on the old shelves of my grocery store. It took me back to the time when I started the business after having just got married. My son Mamdouh, Ahmed’s father, was not even born then,” he recalled.

The prices of the Corona products made Hussein smile. “They still do. When I think that back in the 1960s and 1970s a chocolate bar that used to sell for three piastres or less is now selling for more than LE5,” he said.

But the prices of the Corona products are less expensive than those of now more popular brands. “When you have a product that is slightly less expensive at a time when the product of choice is getting more and more expensive, there is an obvious chance for the less expensive product to make its way. This is especially the case when it comes to non-essential products,” Hussein said.

Bimbo

He added that the quality of the product was also “very decent and can compete with the dominating brands. It has made it possible for Corona products to find their way back onto the market.”

Hussein said that at the beginning of the Corona comeback, it was mostly parents who were familiar with the products that would encourage reluctant children to try them when the children wanted to stick with the brand they were familiar with.

“But eventually things picked up. I would not say that Corona products make up even 50 per cent of my sales of chocolate, but Bimbo makes up over 50 per cent of my sales of chocolate biscuits,” he said. “The market does not make swift changes in just a few years. It takes a while. When Corona was retreating, it took a while for dedicated clients to stop asking for its products,” he added.

According to Doaa Salah, head of marketing at Corona, “Bimbo is a key brand that carries a lot of love with it. This is possibly why its comeback was the easiest — although I have to say that Bimbo was also never fully abandoned by those who love it, even when the local competition was at its highest and when multinationals had uncontested control of the market.”

The golden single-wrapped chocolate biscuit, with a drawing of a happy child on it, is now back in a flow wrapping, though still with the same drawing. It comes, however, in a variety of sizes, and with diverse types of chocolate.

“So, we still have the original Bimbo, but we also have a dark chocolate version and a line of non-coated chocolate biscuits called Negrita,” Salah said. She said the comeback strategy for the Corona brand was precisely based on this mixture of the original with the new.

This was also the case with chocolate and fruit fillings. Corona kept its strawberry, orange and lemon lines, but it also “successfully introduced dark-chocolate mints.” Corona slightly sweetened coco that used to be part of every chocolate cake in every Egyptian kitchen for decades was also joined with a non-sweetened coco that “was very well received”, she said.

“I guess that there again it is important to remember that Corona coco never went fully out of fashion because it is also a loved product,” Salah said.

She is convinced that diversifying the product line and catering for new market demand are essential for any sustainable comeback. However, she is also aware that the promotion of Corona, which is based on direct outreach to potential clients rather than through TV commercials, is in part dependent on the nostalgia that this brand brings.

“It is true that the majority of the population today was not even born when Corona products were at the top of the market, but there is a nostalgia associated with the brand that can even lure those who did not grow up during the best days of our chocolate bars,” Salah said.

Corona team 1947

A TASTE OF MEMORIES: Dina Al-Gharib is one of Egypt’s top DJs. Her profile picture on Facebook is the outer wrapping of a Corona butter chocolate bar with its distinct turquoise blue colour.

“I love Corona so much that when one of my friends decided to help me set up a Facebook page in 2011 right after the 25 January Revolution, he thought that a Corona wrapping would make a perfect choice for my profile picture,” Al-Gharib said.

Even with the many singers and musicians that Al-Gharib is in love with, she would never think to change this profile picture. “My favourite of all the Coronas was the small full-cream chocolate bar, and the butter chocolate was my second favourite. But when my friend was helping me set up my Facebook page, he could only find the wrapping to the butter chocolate bar,” she recalled.

Unlike the full-cream and the hazelnut chocolate, Corona had never discontinued its butter chocolate bar. For Al-Gharib, any of the Corona brands should be celebrated “because it is a distinct taste of childhood. At the very first bite it is my childhood all over again,” she said.

She remembers that when growing up in Heliopolis in the late 1960s and early 1970s she and her three brothers would always get a Corona treat from their father when they did well at school or in sports.

“He had a small blind corner cabinet inside a cupboard that he would open with a big smile to get out one of the Coronas, mostly the full-cream ones, and to hand it over when he was happy with one of us or all of us,” Al-Gharib remembered.

Old advertisment

All her life Al-Gharib has continued to cherish Corona. Despite all the chocolate varieties that she got to taste during overseas travel with her parents when Egypt was still unfamiliar with imported products until the late 1970s when Port Said became a duty-free zone, Al-Gharib always cherished Corona.

Today, Corona might not taste exactly the same to Al-Gharib, however. Like many other people in their 50s or above, Al-Gharib has a better recollection of the taste of Corona in the past. But also like them, she can still taste the past in the chocolate of today, even if the recipe is different or the ingredients are not quite the same.

Psychiatrists have long agreed that most of us have memories of food that can take us back to childhood. Food memory is one of the most obvious manifestations of involuntary memory, whereby a whole stream of memories is ignited by a small trigger.

In his novel A la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past), the French writer Marcel Proust evoked this issue as he followed his narrator’s remembrance of his childhood experience into his adulthood in the 19th and 20th centuries in France.

The taste of small cakes called madeleines is essential to the narration.

“And as soon as I had recognised the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy), immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like a stage set to attach itself to the little pavilion opening on to the garden which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated segment which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the square where I used to be sent before lunch, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine,” Proust wrote.

Egyptian psychiatrist and novelist Basma Abdel-Aziz says there is a physiological reason for the coding and decoding of small things that can cling on to the memory during a certain experience and the way such small clues can trigger intense recollections at a given moment. “Smells and tastes are certainly part of this exercise,” Abdel-Aziz said.

She said that as much as the right coding of smells and tastes could bring back good memories, there were also small clues that could trigger bad memories and even traumas. “So, as much as the taste of a chocolate bar can bring back a whole outburst of happiness from the past, this chocolate bar if associated with a moment of distress could recreate a full trauma. This is because the human memory is very complex,” she explained.

This could also be the case with other cues to other senses. Several studies have upheld the hypothesis about olfactory cues and their ability to increase the emotional intensity of autobiographical recollections relative to verbal or visual cues.

According to Abdel-Aziz, it is often the case that individuals who have been subjected to trauma can recall the moments of trauma at the mere exposure to any of these cues, “the taste of a particular dish, a particular voice, or the site of a lamp or a chair, for example,” she said.

Psychiatrists who try to help people get over their traumas also try to incite their memory to bring back good recollections because these can help the brain to produce its own natural anti-depressants. Regenerating good moments from memory, Abdel-Aziz added, is also an exercise that yoga instructors try in their high-level courses.

In this sense, Abdel-Aziz argued, for some people a moment with their childhood chocolate could well bring back a stream of positive energy that emerges from coded pleasure in the memory.

Books about chocolate

TRICKS OF CHOCOLATE: In 1999, UK author Joanne Harris’s novel Chocolat included the idea that chocolate can be used not just to trigger pleasure and sensuality but also to trigger rebellion.

Her character Vianne Rocher arrives in an otherwise quiet Catholic village in the south of France to open her chocolate store in the midst of Lent when the consumption of chocolate could be seen as sinful. The fact that the store, La celéste praline, is situated opposite the church is seen as a sign of rebellion.

According to professor of English literature at Cairo University Sonia Farid, the novel is not just an account of a chocolate-maker who challenges the rules by insisting on selling her chocolate and on making recipes customised to people’s temperament, but it is also about “chocolate as part of a velvet revolution”.

Velvet revolutions are peaceful uprisings like the one that brought about the dissolution of the former Czechoslovakia in January 1993. “Or they are like our 25 January Revolution in 2011. This is why I used this novel for a paper I presented to a conference on literature and revolution in the wake of the January Revolution,” Farid said.

In Chocolat, Rocher, witch-hunted for her chocolate tricks that had even brought a priest to intrude into her affairs, holds a chocolate festival in Easter and is later forced to close her shop and escape the parish. “But it was society that had been touched by the power of chocolate — and in this context chocolate stands for an alternative and less-restricted lifestyle,” Farid said.

The 1989 novel Like Water for Chocolate by Mexican novelist Laura Esquival is another literary work where the link between food and life is captured. In this novel, Esquival does not make any direct reference to chocolate, except for the title, which is a metaphor that stands for the “boiling point” of water before chocolate is added to it in Mayan culture.

In the novel, the character Tita is denied the chance to marry Pedro because of traditions that only allow him to marry her elder sister while she has to live unmarried to look after her parents. Tita’s sadness is passed on through her cooking for her sister’s dinner, and when they start to eat the food they also start to cry during the wedding.

“This is what we call magical realism: it is a magical moment that has nothing to do with actual magic,” Farid said. “In oral traditions like those of Latin America, food was the only weapon that women had to pass on their emotions or to show their rebellion,” she added.

According to Farid and Abdel-Aziz, chocolate is not always just about chocolate. It can be about more — be it joy, sadness or rebellion. It could be about a particular moment, a particular memory, or even a course of events.

This idea is at the bottom of the promotional strategy that Corona is planning to use to celebrate its centenary. “We are talking about a celebration that would start later this year and continue through Christmas, the New Year, and a few months beyond,” Salah said.

It would include the release of “new versions of some of our old products, where we would stick to the main recipes but bring in the taste of modernity.” There will also be special editions for special occasions, she said. This year, Corona has produced a colourful paper lantern full of mini Corona bars.

“It was very successful this year, and we are planning other ideas for other occasions and feasts throughout the year,” Salah said. “We want to make Corona associated in the minds of today’s Egyptians with good moments just as it is associated in the minds of the older generations with the delights of their childhood,” she added.

Slogans such as “The taste we love and indulge in” and “Corona is for us to eat together” will be used, she said.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 30 May, 2019 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: Rememberance of Chocolate past

Short link: