A theatre adaptation of The Forty Rules of Love – based on the bestselling book by Elif Shafak – ran for seven weeks at Cairo's El-Salam Theatre, garnering critical acclaim and wide popular interest.

The play is directed by Adel Hassan, and was adapted to theatre through a writing workshop headed by Rasha Abdel-Moneim, with Yasmine Emam and Khairy El-Fakharany.

The play steers away from the original book in several ways, yet it manages to stay faithful and even highlight the essence of the story, its characters and timeless wisdoms.

Parallels: Script to stage

A story within a story, Shafak’s book draws parallels between two scenarios; Ella Rubenstein starts working for a literary agency and is given the book ‘Sweet Blasphemy’ by Aziz Zahara, which tells the story of the ancient Sufi poet and mystic Jalaluddin El-Rumi and how he met and was influenced by the wandering dervish Shams of Tabriz.

Perhaps Shafak had meant to contemporise the story and make it more relatable to modern readers through Ella’s narrative, which served to show how the values depicted can apply to anyone, anywhere, at any time in history.

In fact, a passage from the book mentions this, as Aziz writes to Ella that he thinks “the 21st century is not that different from the 13th century… [both are] times of unprecedented religious clashes, cultural misunderstandings, and a general sense of insecurity and fear of the other…the need for love is greater than ever.”

The book’s main characters Ella and Aziz are eliminated from the play, which instead focuses on the ‘Sweet Blasphemy’ story, the development of Rumi and Shams’ relationship, and its effect on those around them, as well as the spiritual values that boil down to meeting all aspects of life with love.

This dramatic adaptation takes us straight to the core of the text, which is truly the most interesting part of the novel.

By eliminating Ella Rubenstein’s part, audiences are transported to 13th century Iraq, presenting a play that contemporises and reaches out to a wider audience.

The play includes classic Sufi chants to the poetry of Ibn Al-Farid and Ibn Arabi and music by Mohamed Hosny.

The musical aspect has been critically acclaimed, with powerful and emotional performances by Amira Abo Zeid, who also takes on the role of Kimye in the play, and Samir Azmy, whose Inshad opens the play and complements the story by both linking and separating the acts from each other.

While the book tells most of the story of how Shams and Rumi met on a linear timeline, the play does not, and for the first half goes back and forth in time.

The play opens with everyone, topped with Rumi, looking for Shams, who seemed to have disappeared. While some are devastated with loss, others are relieved, while others are angry at the mess he left behind, the suspense builds up as we try to understand where he is and what he has done to prompt such mixed reactions.

In between these scenes, we see Shams going about his journey to meet Rumi for the first time. Perhaps this narrative is the only one unfolding in a linear manner, until at some point, both narratives meet and the play continues on the same timeline.

Another main difference between the novel and play is in how the fate of Shams is revealed in the book’s first chapters, while the play leaves it till the end and to the imagination.

The characters, however, are depicted similarly on stage as they are in the book.

Played by Bahaa Tharwat, the grounded, mystical Shams’ piercing comments, confidence and know-it-all attitude is easily taken for arrogance.

Rumi’s kindness, wisdom, and willingness to transform is palpable in the performance of Ezzat Zein.

Faithful to the book, we also find the character Kimye (Rumi’s wife) and her patience, Kerra’s romanticism, Desert Rose the Harlot’s desperation mixed with bravery, Aladdin (son of Rumi) and his aggressive jealousy, The Novice’s over eagerness, and Baybars the Warrior’s double standards.

While the storyline is abridged for dramatic effect, most if not all of the rules of love make it to the stage. Sometimes through Shams himself, other times announced by the Sufi master Baba Zaman, who is semi-permanently present on stage.

The rules are also presented through a voiceover of a character’s thoughts recalling Shams’ teachings.

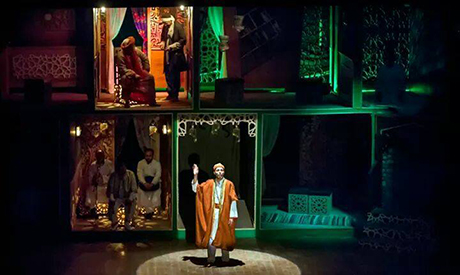

The Forty Rules of Love at El-Salam Theatre (Photo: Artistic Theatre House)

A classic approach

The elaborate, stylised set is characterised by arabesque, Islamic stars and vivid patterned fabrics donning the furniture and walls. It is visually busy, but all serves to evoke the aesthetics of 13th century Iraq.

Designed by Mostafa Hamed, it is comprised of two floors placed up-stage. The bottom floor has five small compartments, while the upper has four, each of which is used as a separate room and fulfils different functions.

Director Adel Hassan went for a classic set treatment with a symbolic division between upper and lower realms.

The upper floor is where the spiritual discourse occurs; this is where Rumi and Shams spend most of their time in the study, and where Baba Zaman sits in another adjacent room.

The ‘worldly’ interactions take place on the bottom floor; conversations between the jealous sons of Shams or the locals unwelcoming of Shams’ presence, as well as the town’s brothel and tavern.

Interestingly, the mosque where Rumi is preaching is also placed on the bottom floor. However, in relation to his time with Shams, which is in an even ‘higher’ place spiritually speaking, the placement still makes sense.

This top and bottom dynamic is also translated in the movement of characters between both levels.

In one scene for example, Kerra, who was jealous of Shams for taking all of Rumi’s time, visits the upper floor to ask a question about the Quran, and meets Shams.

Their interaction leaves her enlightened and visibly enchanted, and she spins with joy, mimicking the whirling dervishes on stage.

The bottom left and the upper right rooms are reserved for two whirling dervishes, who start their spinning on queue with the music. Their placement makes for a frame, with the play’s events occurring between them, and offers a visual and metaphorical balance by linking both floors.

Period costumes by Maha Abdelrahman were executed with attention to colour and symbolism, changing with the characters as the play develops.

Rumi in the first half of the play is donning a fancy, glittering black cloak, appropriate for a man of his status. After spending time with Shams, who teaches him non-attachment, his wealthy-looking fabrics are replaced with the more modest, plain white galabeya.

Shams himself is dressed in unassuming travel-comfortable garments, with a colour scheme easy on the eye; blue, grey and beige.

Kerra at first is wearing colourful dresses, then after experiencing some enlightenment is donned in white, now fully resembling the whirling dervishes, as she spins in sync with them.

The lighting, overseen by Ibrahim El-Forn, plays an important role in carrying the dynamics of the story.

Although, like the set, the lighting was busy and complex, it was not distracting, but served to establish the mood.

Lamps on stage as part of the set created a warm ambiance, while spotlights were used to highlight scenes and lead the eye from one place on the stage to another.

In the end the audience is left with a great deal of quotes on love and life, and a vibrant visual memory of the play’s aesthetics.

We are also left meditating on the dependence on an ideal, what the absence of Shams will do to each of the characters.

The play's seven-week staging concluded last Saturday. However, it will return to El-Salam Theatre on 3 June, the 7th day of the holy month of Ramadan, which will contextually compliment the play's themes and aesthetic.

The Forty Rules of Love at El-Salam Theatre (Photo: Artistic Theatre House)

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

Short link: