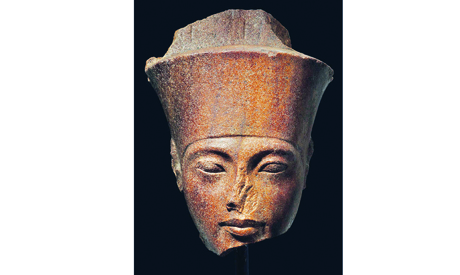

The auctioneers Christie’s and Sotheby’s are famous institutions where antiquities are auctioned almost every month. We see the sales of stelae, statues, ushabtis, pottery and furniture there, but little is done to stop them. We also see museums buying stolen Egyptian artefacts without consulting the Ministry of Antiquities in Cairo. If we review a few examples of the auction sales, the last notable one was for the head of a statue of the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The auction house in question did not want to present the Ministry of Antiquities with any documents to show that the head had left Egypt legally, and at the same time the UK authorities did not want to see evidence that the statue had come to the country in an illegal way. Eventually, the statue was sold to an anonymous buyer. The auctioneers did not want to reveal the name of the person who had paid $6 million to buy the head. We expect that this statue will not now go to a museum but will be shown in the house of a rich person. There are many similar examples of artefacts that are tucked away in the houses of wealthy individuals.

In my opinion, the major problem here is with the museums. We in Egypt have written letters in the past to museums all over the world requesting them not to buy stolen Egyptian artefacts and warning that if they buy such a statue or coffin we will break off cooperation with them. If someone wants to excavate in Egypt, they can’t be involved in dealing in antiquities. If any evidence is found linking a person (Egyptian or foreigner) to the trade in antiquities, then all ties must be broken. He or she has no place among us.

However, for all those who are upset to hear about this issue and want to help, it is also important that they understand the history of the antiquities market.

There have been many examples of museums that have bought stolen artefacts over past years. It happened when I was the head of the Giza Plateau and the late Ahmed Kadri was head of antiquities, for example. We received information that the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had bought some reliefs stolen from the Old Kingdom tombs at Deir Al-Gebrawi.

I travelled with the late Gamal Mokhtar to the opening of the Ramses II exhibition at the Museum of Science in Boston in 1988. We had lunch with the director of the Museum of Fine Arts and asked for the return of the reliefs. The director agreed, and the reliefs went back to Egypt. When we examined the accompanying paperwork, we discovered that the person who had sold the reliefs to the museum had forged the signatures of the Cairo Museum authorities, because before 1983 one could take antiquities outside the country, but before transporting them one needed to obtain permission with a stamp from the Cairo Museum verifying that they had left Egypt legally.

The late William Kelly Simpson, a great Egyptologist and the curator of Egyptian art at the museum, told me that they had bought the Deir Al-Gebrawi reliefs rather than let them be bought by a rich man who would hide them in his home. But in my opinion if museums are open to buying stolen artefacts, this will increase the theft of antiquities.

The second example is the Saint Louis Art Museum in the US that bought the funerary mask of a 19th-Dynasty noblewoman Kanefernefer. The museum claimed that it had written to the Cairo Museum, but it had still bought the mask despite the fact that it was registered at the Cairo Museum as an object in the collection. We had many disputes with the Saint Louis Museum, and I still cannot believe it can have this mask knowing very well that it was stolen.

What do they tell children visiting the museum? This is a very unethical practice, and I will not stop talking about the scandal that it has created. The Homeland Security Department in the United States tried to help us on this matter, but without success. The authorities at this museum are very stubborn and do not want to return the mask.

This mummy mask of Kanefernefer has an extraordinary presence, with its combination of glass inlaid eyes, a gilded face with a shimmering, almost lifelike translucence, and a realistic wig. The craftsman who fashioned the wig out of thick resin carefully cut and modelled the plaits of hair in the latest style. The red gold colouring of the skin is the result of oxidation on the metal surface, which may be purposeful or merely the product of the sulphurous fumes given off by the resinous wig. The band around the mask’s head and its eyes are inlaid with glass.

All this is written on the official label about the mask. I have told the Saint Louis Museum authorities that they should return the mask to Egypt. If not, I will continue to publicise this case.

Nedjemankh Gilded Coffin

A CASE AT THE LOUVRE: Another case I would like to mention is connected with the Louvre Museum in Paris.

I found out when I was the head of antiquities that the Louvre had bought four reliefs stolen from a private tomb on the west bank at Luxor. When the thieves had entered the tomb, they had cut out specific reliefs and damaged the whole wall. If one goes to see the wall of the tomb today, it is clear that the reliefs were taken, and one can see that all the paintings on the wall were damaged.

I wrote a letter to the director of the Louvre to ask for the return of the reliefs. He came to Cairo and promised that he would return them, but said that the process would take many months. I asked him how an Egyptologist could consider buying reliefs that were known to be procured illegally. I cannot find an answer to this question.

I waited more than six months, but nothing happened. Then the Louvre applied to work at Saqqara in Egypt, and the Permanent Committee for Antiquities stopped the work. Later, as I was going to give a talk to an American group, I received a call from the office of former president Hosni Mubarak. The president said that former president Nicolas Sarkozy of France had called and said we had stopped the excavation by the Louvre at Saqqara.

I asked the president if he had time to listen to the story, which I then explained to him. The president said that we had done the right thing. He said he would be travelling to France and asked me to send some archaeologists to receive the reliefs. These items eventually returned to their rightful home.

Yet another story concerns a museum and the sale of a statue from its collection purely for financial gain. This had never happened before in the history of museums, but it occurred at the Northampton Museum in England. The latter sold a Fifth Dynasty statue of the scribe Sekhemka to a person who has tucked it away as his private property, meaning that no one can now access this beautiful sculpture. This unethical practice is scandalous, and the museum lost its accreditation as a result, making it ineligible for funding from many sources.

Other museums have maintained their reputations and sense of duty. For example, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia has never bought artefacts from a dealer or auction house. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the time of curator Dorothea Arnold helped us a lot in returning many stolen artefacts and even guided us to many cases.

However, recently the Met returned a beautiful Ptolemaic gold coffin to Egypt that had been acquired illegally. It had never consulted with the Ministry of Antiquities about the acquisition, and US Homeland Security collaborated with the Manhattan district attorney in discovering that the coffin had been stolen during the turbulence of the 2011 Revolution in Egypt. I do not know how the attorney-general of New York was involved in the case, but this facilitated the return of the coffin.

All the papers that the dealer had given the Met were fake. I hope that the Met will learn from this case and follow in the footsteps of Dorothea Arnold.

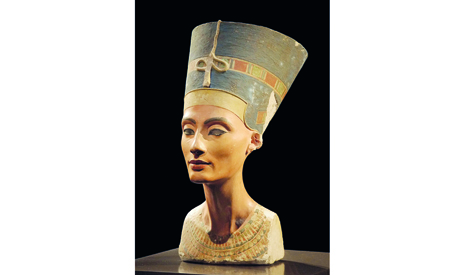

Nefertiti bust

HISTORY OF ANTIQUITIES: The first time that monuments left Egypt was during the Roman Period, when many ancient Egyptian obelisks were moved to Rome.

In the 19th century, Mohamed Ali gave gifts of antiquities to the crown prince of Austria that formed the nucleus of the Egyptian antiquities collection at the art museum in Vienna. In fact, a consular delegation was appointed in Luxor for the purpose of transferring mummies and other artefacts to receiving countries.

Egyptian antiquities became even more important after the world discovered the value of the Rosetta Stone and the hieroglyphic language that was deciphered by the French scholar Champollion in the early 19th century. The Rosetta Stone went to the British Museum in 1801 in an agreement between England and France. Egyptian antiquities then began to be sold under several decrees and laws, with museums around the world buying them and adding them to their collections.

On 12 August 1897, a decree by the khedive Abbas Helmi stated that anyone taking antiquities belonging to the government would be fined between 50 to 100 piastres as well as given a jail sentence of three to seven days. Another decree, this one promulgated by prime minister Ismail Serri in December 1909, established that all ancient buildings and artefacts belonged to the government of Egypt.

The 1912 law said that any monuments found either under or above the ground belonged to the Egyptian government. However, these laws protecting antiquities still permitted their sale, even if they said that the antiquities dealer needed a licence from the antiquities service to buy and sell them and that all monuments that left the country should be purchased by a licensed antiquities dealer. The law further established that the transport of artefacts without a licence was punishable by a year’s imprisonment.

Antiquities Law 215/1951 confirmed a practice that was already extant: foreign expeditions had permission to take 50 per cent of their discoveries in Egypt except for a tomb found intact or a royal statue of limestone. This practice was highlighted during the discovery of the bust of Nefertiti (a statue made out of limestone) and also the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, which could not be taken out as it was found intact.

Another law was issued in 1983, number 117, that stopped the sale of antiquities but gave foreign missions 10 per cent of any finds. When I became the head of antiquities in Egypt, we stopped that 10 per cent. In 2010, the law changed again, making those caught stealing or defacing land on which there were antiquities subject to increased jail sentences.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the Nile was often tapped by foreign adventurers. The Deir Al-Bahari cache of royal mummies found in 1881 by the Abdel-Rassoul family revealed that the sale of other objects from the cache had taken place before the government came to excavate it, for example. One mummy, that of Ramses I, left the cache to end up in the Niagara Falls Museum. The great German Egyptologist Arne Eggebrecht saw this mummy and rightfully said it was the mummy of a king.

Tutankhamun

Bonnie Speed, the director of the Michael C Carlos Museum, later asked the people of Atlanta in the US to save the mummy when the Niagara Falls Museum was closed, and they did indeed buy it. When I confirmed through scientific evidence that the mummy did in fact belong to a king, Speed agreed to return it to Egypt. She is another lady whose name will be engraved in gold.

Meanwhile, the famous bust of Nefertiti in the Berlin Museum left Egypt illegally, and we later collected all the necessary evidence that Ludwig Borchardt, its discoverer, took the bust without legal permission. At that time, the law did not permit any royal statue made of limestone to exit the country. Borchardt wrote in his diary, which no one read except him, that it was a bust of Nefertiti made of limestone. But in the registry, which would be seen by the authorities, he wrote that it was a royal statue made of gypsum. Borchardt put the bust in a box with other objects. The head of antiquities at the time did not open the box, and Borchardt hid it in Germany for 10 years.

I collected all this information and received permission from the prime minister to send the file to Germany. The authorities in Germany wrote back to say that they needed the letter to be signed by the minister. When I received this response, I was in fact the minister of antiquities, but I did not have time during the troubles of 2011 to sign the letter.

I am now organising a committee of Egyptian and foreign intellectuals that will write a petition to ask for the return of the Nefertiti bust from Berlin. I also think that the Rosetta Stone and the Zodiac from the ceiling of the Temple of Dendera, now in the Louvre, should also come back to Egypt.

In the past, imperialism permitted the treasures of Africa to be taken out of the continent. Now, there is an awakening, and those objects should come back to Africa. But some museums are still using the methods of the past to buy stolen artefacts for their own benefit. This is a shameful practice.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 9 January, 2020 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

Short link: