“I was sitting in a reflective mood thinking that there was a time when the Egyptians would celebrate the end of heat waves with the beginning of a new year, according to the ancient Egyptian calendar. I checked into my Twitter account and wrote Tout yeoul lil-har mout (“Tout orders the death of heat”) and was really surprised by the response,” said novelist Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid in an interview with Al-Ahram Weekly.

According to the calendar of ancient Egypt, the basis of the Coptic calendar, Tout is the beginning of the new year. This is the calendar that was used in Pharaonic Egypt. It is mostly associated with the weather and the level of the Nile, and it is therefore still part of the minds of farmers whose traditional times of planting and harvest are still designed according to it.

According to the ancient Egyptian calendar, this week, or more precisely 11 September 2020, is 1 Tout 6262. Across social media this week, there were comments celebrating the beginning of 6262, sometimes called the “Egyptian” year and sometimes the “Coptic” year.

“It is essentially one and the same thing because obviously ‘Coptic’ literally means Egyptian rather than Christian, but it has become associated with the followers of the Egyptian Orthodox Church. It was the Coptic Church that during the Graeco-Roman rule of Egypt insisted on keeping the ancient calendar to protest against the elimination of thousands of Copts who died defending the Orthodox faith and the independence of its church,” Abdel-Meguid said.

Inevitably, this helped mark the difference between the Church of Egypt and the Church of Rome. It also helped mark a difference between the Gregorian and Old Egypt calendars.

For this novelist whose literary production offers a mosaic of “moments of identity”, even if the purpose behind the choice was one of religious creed, it is still also an issue of identity. “It certainly was an issue of identity, and it was this determination on the part of the Coptic Church that kept the ancient Egyptian calendar from being forgotten,” he argued.

This, he said, was why he calls 6262 the “Coptic year” in a double reference to the literal meaning of the word Copt and to the role of the Coptic Orthodox Church in keeping this calendar alive to the point that its months are marked on the front page of Egypt’s leading daily Al-Ahram, along with the western Gregorian and Hijra (Islamic) calendars.

“So, yes, we do have three calendars, and it is in a sense an indication of the many cultural dimensions that we have. But essentially as we have seen with the attention that many people are sharing in celebrating the beginning of 6262, the one thread that brings us all together is the fact that we are all Egyptians in the profound sense of the word,” Abdel-Meguid said.

Unlike the Hijra calendar, which is lunar, the ancient Egyptian calendar is solar, like the Gregorian. It has 365 days that are roughly divided into three seasons, each of which has four months.

Following Tout (Thout) comes Baba (Paopi), which is associated with the harvest. Then comes Hatour (Hathor), which is associated with the planting of wheat, and after it is Kihak (Koiak), which sees the advent of winter and the shortest daylight hours. The following two months are Touba (Tobi) and Amshir (Meshir), when it gets cold before the weather starts warming up.

Then it is Barmahat (Paremhat), Barmouda (Premoude), and Bashnas (Pashons), which are associated with the harvesting and storage of wheat and letting the land rest ahead of the following season. Then comes Baaouna (Paoni) and Ebib (Epip), the hottest months of the year with the harvest of summer fruit like figs, grapes, and mangos. The last two months are Mesri (Mesori) and NeseI (Pi Kogi Enavot), which are the months of the flooding of the Nile River from both the Blue Nile and White Nile.

This calendar is shared with Ethiopia, which on 11 September was celebrating the beginning of a new Ethiopian year, just like Egypt.

Today, Abdel-Meguid argued, not all those joining the celebration of the new year were conscious even of the sequence or for that matter the names of the months of the ancient Egypt calendar. “But it was an affirmation of Egyptian identity, about saying that we are first and foremost Egyptians.”

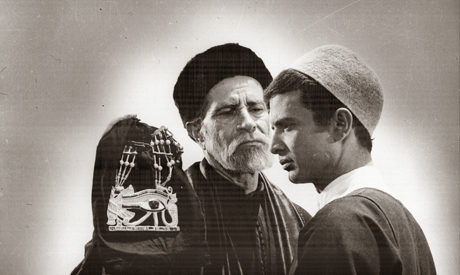

A still from the film The Night of Counting the Years

The pursuit of connections to Pharaonic roots to affirm Egyptian identity is for the most part “a new trend,” he said.

Over the past seven decades when he lived first in Alexandria and then in Cairo, Abdel-Meguid has written much about Egyptian identity, sometimes looking north across the Mediterranean, as for example from Alexandria, and sometimes looking east in the wake of the oil boom that granted the Arab Gulf countries economic and subsequently cultural hegemony across the Arab Mashreq.

Abdel-Meguid has also seen and lamented what he calls the “heavy-handed influence of the Wahabi waves that have hit Egypt, not at the hands of those coming from the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt, but mostly by Egyptians who left the Delta in pursuit of a comfortable situation in the Arab Gulf countries before coming back home with Wahabi norms and views.”

Like other novelists of his generation, Abdel-Meguid has often portrayed free-spirited Egyptians who loved food, drink, poetry, and music being forced by a lack of opportunities in their native land to go to the Arab Gulf cities, later returning with their minds full of Wahabi Islam. “This includes the ideas of Salafi preachers trying to spread the Wahabi version of Islam loaded with isolationism and intolerance,” he said.

In subsequent decades, he said, the connection to Pharaonic roots was hardly recalled as a result. With the exception of a handful of films, the rich and inspiring production of the golden years of Egyptian cinema, there was little room in this new Egypt for Pharaonic-inspired themes. The most famous is Shady Abdel-Salam’s iconic Al-Mummia (The Night of Counting the Years),

With the exception of Egypt’s most popular and least expensive brand of cigarettes, “Cleopatra”, Pharaonic names did not brand Egyptian products. Egyptian manufacturers often looked to French and English brand names for their products instead. Of the many volumes he produced, the novels carrying Pharaonic titles, such as Kefah Tiba (The Struggle of Thebes) are the least popular, at least in terms of sales, of the Naguib Mahfouz literature.

During the same decades, Abdel-Meguid argued, using Pharaonic names for boys, such as Isis and Abnob, as was customary in Upper Egypt, declined significantly in favour of either very modern and often foreign names, or names of Christian saints, or prominent Muslim figures.

But for Abdel-Meguid, from the beginning of the rule of Mohamed Ali in the early 19th century until the Free Officers took power in the 1952 Revolution, the vast majority of Egyptians thought of themselves as either Egyptians, with no particular association with the ancient Egyptian heritage, or as Muslim or Christian or even Jewish Egyptians.

Of course, he added, there were also those many foreign nationalities who came to live in Egypt, particularly in Alexandria, and defined themselves as Alexandrians. “And then there were the often marginalised groups like the Nubians, the Bedouin, and the Imazigh (Berbers) who live on the borders of the country,” he said.

Abdel-Meguid

“Those who count as part of a minority had perhaps a more poignant sense of what might be called a sub-identity, but there was still no direct connection to pharaonic roots,” he said.

“Over the years since the beginning of the Graeco-Roman period, through the years of the Arab conquest, through the many Islamic rulers that took over Egypt until it was again ruled by Egyptians in 1952, the Egyptians perceived themselves as nothing but Egyptians. They would accommodate newcomers, like Assyrians and Armenians, and those newcomers would easily integrate into the fabric of Egyptian society, but the Egyptians, with very few exceptions, would not part away with their identity as Egyptian — not Pharaonic, but Egyptian,” he added.

With the rule of president Gamal Abdel-Nasser after 1952, Abdel-Meguid said, the emphasis was on Arab identity instead. “This was a big thing for Nasser, who perceived Egypt as the heart of the Arab world and was a strong believer and advocate of pan-Arabism,” he said. This, he added, was perhaps the moment of the re-definition of the identity of Egypt as the leader of the Arab world.

“Because Nasser was so popular and because this was a moment when Egypt was faced with colonialist aggression and had to go to war with Israel, it felt natural for many Egyptians to define themselves as Arabs,” he argued. “Some might not have subscribed to this trend, but it was a dominating one until the defeat of 1967 when the question of identity was again pursued.”

Ironically, he said, it was during the rule of Nasser’s successor, president Anwar Al-Sadat in the 1970s, that the association with the country’s Pharaonic roots was re-introduced when Sadat squabbled with the Arab states.

“In fact, however, this was just a matter of propaganda, because in fact it was during the Sadat years, as part of his new political association with Saudi Arabia and his attempt to quell the then-strong leftist movements, that the promotion of Egypt’s Islamic identity was heavily emphasised,” he argued.

The cover of The Struggle of Thebes

Abdel-Meguid accepts that there were many moments when the debate over Islamic identity was pursued, especially when Egypt gained self-rule under the former Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, with some rejecting this as a separation from the all-encompassing Muslim nation.

However, he argues that what was at stake in the 1970s, “and it lingered on during the 1980s and 1990s,” was not Islam but Wahabism. “It was not brought to Egypt as Wahabism, as those who promoted it called it ‘real Islam,’ when in fact it was a 19th-century product,” he argued.

Towards the end of the 1990s and through the first decade of the 2000s, Abdel-Meguid argued, there was an urge on the part of many to ask the question of identity once again. “This was not a high Arab moment. The impact of the Gulf declined in the wake of the Gulf War, and the call of pan-Arabism was effectively declining.”

According to Abdel-Meguid, this was a time when people, especially younger people, were asking questions about pre-1952 Egypt. “They were curious about the Egypt they never knew and that they never read about in the history books at school,” he said.

This curiosity was in part encouraged by the books made available through the Maktabet Al-Usra (Family Library) series, a state-sponsored scheme to provide books at affordable prices for all. “Under this project, there were many titles on the civilisation of ancient Egypt that brought to the attention of the younger generation a very rich layer of their history that was only presented at school as a list of warriors who built lots of monuments — a very unfortunate and unfair representation,” he said.

This was coupled with a growing trend to recall simplified versions of Pharaonic-style accessories, including jewellery, that was produced and made in a range of metals, including affordable copper pieces.

“This was part of a wider debate about politics, religion, and identity. There were questions about the Mohamed Ali family and the way Egyptians looked and dressed before the dress styles of the Arab Peninsula were embraced, both in the cities and the rural areas,” Abdel-Meguid said.

“Social media played a role, as people started sharing photographs of their parents or grandparents at schools, universities, villages and so on,” he added.

Then came 25 January 2011 as part of the Arab Spring Revolutions. There again, Abdel-Meguid acknowledged, there was a brief moment of Arabism. “There was a sense that the Arab countries were pursuing freedom and, this time, democracy as well,” he said.

Not for long, however, he argued. Because figures from Political Islam were elected in many Arab countries, and there was unease over this trend both from the state establishment and anti-Islamist quarters, there was also a return to an all-encompassing Egyptian identity to fend off the rise of Islamism.

“That was not a moment when the question of identity was answered. It was a moment when the question was becoming more complex,” Abdel-Meguid argued. In fact, the definition of the Egyptian identity and deciding on its roots and the shades it can accommodate from many cultural and religious influences “was and is becoming the question”.

“In this context, some people may recall or introduce the Pharaonic connection, and they might celebrate things like the year 6262 and take pride in the fact that we are such an old and established nation with a very rich civilisation,” he said.

Abdel-Meguid is convinced that the definition of Egyptian identity today cannot be separated from its Pharaonic roots. “Our agricultural system for the most part, the way we bury the dead, and the way we celebrate the birth of newborns, some very particular recipes, and much more come from these roots,” he said.

“But there are also many other influences that cannot be dropped, and then there is modernity that cannot be ignored either,” he added.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 17 September, 2020 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

Short link: