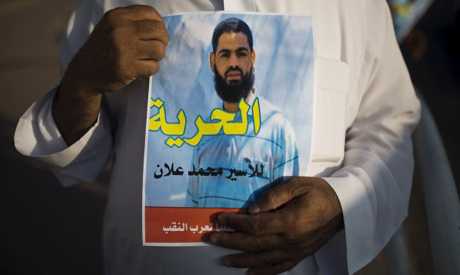

A Bedouin demonstrator holds a sign during a protest in the southern town of Rahat, Israel, in support of Palestinian prisoners Mohammed Allan, who was in the ninth week of a hunger strike against his detention without trial, August 18, 2015 (Photo: Reuters)

A Palestinian prisoner's hunger strike has sparked new calls for Israel to curb its use of a form of detention without trial, with activists charging routine abuse of a measure aimed at preventing attacks.

Mohammed Allan, 31, ended his hunger strike on Thursday after Israel's top court suspended his administrative detention. He had twice been in a coma.

The lawyer said to be a member of the militant group Islamic Jihad had been held since November and has reportedly vowed to resume hunger strike if the courts reinstate administrative detention against him.

The measure allows internment without trial for six-month intervals that can be renewed indefinitely, with Israeli officials saying it is an essential tool in preventing attacks and protecting sensitive intelligence because it allows authorities to keep evidence secret.

It has been strongly criticised by rights activists, who have called on Israeli authorities to prosecute or release such detainees.

Rights groups say international law allows for such detention under extreme circumstances, but that Israel uses it as a punitive measure that circumvents the justice system or as a crutch to avoid trial.

Activists have called on Israeli authorities to charge or release those held under administrative detention.

"Our research into the way Israel uses administrative detention vis-a-vis Palestinians concludes that Israel violates this very narrow allowance and uses it in a very wide, extensive way," said Sarit Michaeli, spokeswoman for Israeli rights group B'Tselem.

This is "unacceptable legally and morally", she said.

According to B'Tselem, some 370 Palestinians are currently held in administrative detention compared to three alleged Jewish extremists.

The Jewish suspects were held amid an outcry following the July 31 firebombing of a Palestinian home that killed an 18-month-old child and his father.

Rights groups have also criticised those moves, pressing authorities to follow due process.

Israeli officials did not respond to request for comment on Sunday, but Defence Minister Moshe Yaalon last week defended the practice.

"Administrative detention of an Arab or a Jew is a Draconian step, but when there is no choice, you need to protect yourself," he said.

"One needs to be very, very careful, but I have no doubt that we have put the right people into administrative detention."

Administrative detention dates back to British-mandated Palestine, though Israeli military law is used for cases involving Palestinians in the West Bank.

The degree of its use has varied, with the number of detainees skyrocketing during the first and second Palestinian intifadas, or uprising.

Detainees have been held for between six months and several years.

Many Palestinians have gone on hunger strike in protest, though few have continued as long as Allan's.

In July, Khader Adnan was released after a 56-day hunger strike to protest his administrative detention.

Detainees are allowed to appeal to the courts, but activists say the chances of having their detainment overturned are extremely slim.

A recent example cited by rights groups is the case of Khalida Jarrar, a Palestinian legislator first held under administrative detention before later being charged in military court.

While the 12 charges against her have been criticised by her supporters as well, rights groups say they raise the question of why administrative detention was necessary.

In the case of Allan, it is not possible to know details of the accusations against him.

Last week, Israeli security forces issued a statement saying he was arrested in November due to alleged contacts with an Islamic Jihad "terrorist" with the aim of carrying out large-scale attacks.

He had also served prison time between 2006-2009 for allegedly seeking to recruit suicide bombers and providing assistance to wanted Palestinians, according to the statement.

His lawyer said he was never informed of the recent allegations against him, and his friends describe him as religious, but not radical.

Allan's hunger strike sparked debate among Israelis as well, with some arguing that he should have been force-fed under a law passed last month allowing for the practice.

Far-right Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel was among those who argued for force-feeding but he, too, said administrative detention was being overused.

Uriel said the measure should only be employed in cases of "ticking bombs".

*The story was edited by Ahram Online.

Short link: