Two neighbouring cells and a hole wide enough to deliver shy attempts at communication. Two neighbouring cells and a hole wide enough to permit the flow of conversation. Two neighbouring cells and a hole wide enough to witness a budding love story, that of comrades Amer and Raghda.

Amer and Raghda were in adjacent cells in a Syrian prison some 15 years ago. Amer, a Palestinian freedom fighter, and Raghda, a Syrian communist revolutionary, covertly dug a hole into the wall, and for months spoke to each other through this small opening. Upon their release, their love story culminated in wedlock. Happiness ensued, and was further reinforced by four beautiful children.

There you have it, every reason to render this ‘a Syrian love story’ par excellence, as the very title of British filmmaker Sean McAllister’s 2015 documentary suggests.

But this is only one fragment of the story.

The documentary starts almost two decades after the couple’s marriage, and follows them over five years (2009-2015) — thus acting as a witness to both the police state that dominated Syria pre-Arab Spring, and the dream of revolution that was introduced in 2011, and which, thanks to a bloody crackdown, was brutally interrupted.

As the film proceeds, two stories unravel in parallel; that of a nation grappling with revolution, and that of the fellow inmates-turned-lovers, who must remain in harmony as the very idea of “home” is being re-examined.

When the documentary opens, we are in the beauteous coastal town of Tartus.

It is 2009, and we learn that Raghda, 40, was recently put back in prison for daring to pen a novel whose main protagonists are two prisoners in love, the plot paralleling her own story with Amer. For his part, McAllister arrives in Damascus, where he meets Amer and is told about Raghda’s story.

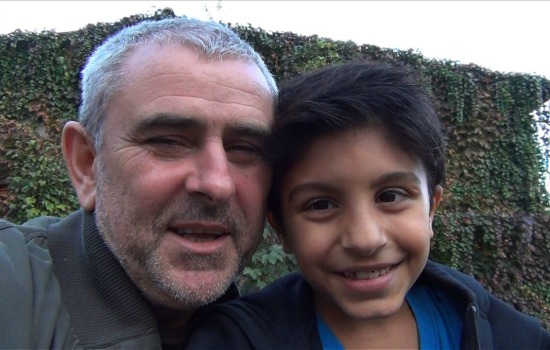

(Photo: still from A Syrian Love Story)

Amer, 45, is aggrieved by the ugly course his life has taken. He has to deal with a two-tiered agony: that of the absence of the beloved, a lingering state of waiting which he tries to terminate through organising protests and raising awareness about Raghda’s story, and of also having to witness traces of this tragedy in the eyes of their four children, especially 14-year-old Kaka, who does not like Al-Assad because “his boys took my mother.”

Against this gloomy reality, the only consolation for Amer and the kids become the camera-phone footage they have of Raghda.

It is two years later – and precisely in the midst of the Syrian revolution in 2011 – that Raghda is eventually released as a result of international pressure on the Al-Assad’s regime. The family celebrates their long-awaited reunion, but alas, the story has just begun. For this unfolding revolution forces the film to take an entirely new course, one that McAllister audaciously accepts.

Now out of prison, Raghda must on the one hand deal with the trauma of yet another ugly prison experience, and on the other hand, make her own contribution to the Syrian revolution, itself a dream she had long aspired for.

We see the family struggle to keep itself intact as it witnesses the re-moulding of the idea of “home” — on both the level of the family as well as the nation. Through this brilliant interweaving of the “private” and “public,” McAllister is posing a crucial question: What remains of love, when the very idea of home – as both a catalyst of this love and a guardian of its continued existence – is being remoulded?

(Photo: still from A Syrian Love Story)

To further complicate matters, both Amer and Raghda have different stances on their potential contribution to this moment in their country’s history. For Amer, it is the safeguarding of family in the midst of chaos. For Raghda, however, the question is more complicated and tugs at her own understanding — or lack thereof — of her own self. Is she first and foremost a mother and wife, or a revolutionary?

As the revolution intensifies, the film follows the family’s relocation to the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp, then to neighbouring Lebanon, and finally to France, where they seek asylum and are granted refugee status. Every move away from home plunges the family deep into grief.

McAllister’s hand-held camera shots and intimate close ups communicate the states of agony and exile, or more precisely, agony as an offshoot of exile. The story of Amer and Raghda's family becomes but one manifestation of the entire Syrian saga; a microcosm of the macrocosm.

In Lebanon, they dream of Syria. In France, they long for their lemon tree back in Tartus. For them, these fragments of memory constitute the “sweet days” that they constantly yearn for.

Perhaps this state of longing for home as they know is most poignantly manifest in an intimate mother-son scene, where both the mother and little Bob are crying their hearts out. They gently reassure one another that it is only a matter of time before they can recover their “home.”

McAllister’s film constitutes yet another successful attempt at humanising a contemporary national tragedy that continues to be spoken of merely in numbers. In A Syrian Love Story, the abstract becomes tangible as we see firsthand how a revolution takes its toll on a Syrian family.

(Photo: still from A Syrian Love Story)

Moreover, the documentary looks beyond the tragedy of exile. Instead it forces us to consider what happens beyond this act of forced exile.

The lemon tree becomes a symbol of home. It offers a story, itself a part of a larger attempt at preserving the Syrian collective memory, especially in the face of the fierce annihilation of both space and memory, or space as memory.

In as much as McAllister delivers an intimate family portrait, he also acts as a main protagonist in the film, adding yet another layer to this tale of love and revolution.

Months into the revolution, and precisely in October 2011, McAllister himself is captured by Syrian secret police for filming, a story that made international headlines at the time. Adamant on telling the family’s story, he decided to complete filming upon his release shortly after.

McAllister does more than capture a Syrian family. He occasionally leaves the comfort of his position as filmmaker and acts as a mediator between family members. He does not shy away from developing an intimate relationship with the couple’s four boys.

Taken together, McAllister’s choices tug at the ever-present question of whether or not artists should maintain a space from the subjects of their art.

More than just capturing the minutiae of a national tragedy, A Syrian Love Story takes us beyond the confines of the movie theatre and onto a place in memory imbued with the voice of Palestinian musician Kamilya Jubran as she sings the following lines from Mahmoud Darwish’s repertoire,

“They threw him out of every port, and took away his young beloved.And then they said: You're a refugee.”

Perhaps this family tale begins where Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry leaves off; it traces the refugee's response to this brutal theft of the beloved; the theft of one's homeland. And perhaps it is for this reason above all that we should celebrate McAllister’s documentary.

(Photo: still from A Syrian Love Story)

A Syrian Love Story will be screened again on Tuesday 8 November at 6.30pm at Cinema Amir, Alexandria, and on Sunday 13 November at 6.30pm at Cinema Arkan, Port Said.

Check here the complete programme of Panorama for Cairo, Alexandria, Ismailia and Port Said

Ahram Online is the media sponsor of the Panorama of the European Film and of Zawya

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

Short link: