Ibrahim Saleh, a young man in his 20s from the Suez Canal city of Ismailia (140 km from Cairo and the seat of a 5,066 km governorate with a population of 750,000) is in the process of establishing an art space there.

He hopes the space will be a hub for aspiring filmmakers and movie enthusiasts in the local community. In addition to filmmaking workshops there will be a cineclub, screening much more than movie theatres the governorate can offer, replacing movie night at friends’ homes.

“We started out as a group students, fresh graduates, bankers, engineers and doctors,” Saleh says. “And we were all very keen on watching, even making movies. Some of us later joined the Film Institute in Cairo; they have come back now to be part of the project. We want to help the young people of Ismailia to taste cinema and maybe make their own films.”

In August 2016, Youssef Shazli and Alya Ayman, co-founders of the by now famous Zawya Art House space, organised a workshop entitled Managing Alternative Screening Spaces Outside Cairo, aiming to encourage those interested in cinema and filmmaking outside Cairo to start their screening spaces.

“When we established Zawya in 2014,” Ayman, head curator at Zawya, recalls, “we had the vision but we lacked the experience of programming, licensing and managing a space. Only by trial and error and the few workshops we joined were we able to successfully continue. So it felt important to transmit our experience to the others, especially those far from the centre. In that workshop,” attended by Saleh, “we met very enthusiastic people from different governorates who either already had their own cineclubs or wanted to establish one. Some had started their own zawyas in Ismailia or Port Said.”

Saleh went home to start a Saturday movie night programme at Donia Cinema. “Compared to home screenings,” he says, “it was great to have a truly public, officially licensed screening at a movie theatre following by a discussion with the audience — unprecedented in Ismailia.” But, since they could only use the Donia Cinema so often and there were more Zawya films they wanted to screen, they decided to start their own space.

The problem facing Salah (and, as it turns out, Ayman as well) is money.

“Art house or not, you’re running a space and you need to pay the rent. You have to screen hit releases to attract a big audience,” Ayman says, “and these are generally determined by the big world festivals.”

To screen potentially less popular (experimental, short and classic) films, Zawya introduced the Sunday night movie club — one night a week — which, as it turns out, is always a full house. Aside from ticket revenues, other measures to meet the financial challenge include distribution, licensing and screening partnerships, which help the movies reach a wider audience as well.

Q & A in Cairo Cinema days (Photo: Al Ahram Weekly)

For Yasmine Desouki, the artistic director of Cimatheque Alternative Film Centre in downtown Cairo (which archives and screens archival films three-four times a week), movie availability is a major challenge.

“It is easier with foreign films from Europe or the US, though not all are affordable,” she says, “but in the Arab world there are few proper cinematic archives.”

Zawya started out in one of the theatres at Odeon Cinema before taking up two theatres of its own in Donia Karim Cinema, but Cinematique consists of two apartments and uses a room of limited capacity for screening. Its ticket revenues cannot help with screening licenses, which often require sponsors.

The state-funded African Cinema Club run by the Luxor African Film Festival (LAFF) in cooperation of the Cultural Development Fund aims to screen LAFF movies to a wider audience in Cairo. It holds one screening at the Al-Hanager space on the Opera House grounds on the first Saturday of every month — too little for LAFF director Azza Al-Husseini, who feels that with more funds much more African cinema could come to Cairo.

“With such a limited budget,” she says, “we cannot afford the licenses of most feature films we’d like to screen, nor can we realise our dream of operating outside Cairo as well.” But with a full house and successful discussions with major African figures, Al-Husseini is still proud of the club.

Smaller endeavours meet the same set of challenges. As the cinema and music programme manager at Darb 1718 — an art space in Fustat where films are projected in the open air while the audience sit on beanbags — Ahmed Yehia says it is hard to find popular enough movies to screen for free. After a stint obtaining such movies from embassies and cultural centres, which did not prove popular, Yehia turned to Zawya, cutting a deal to obtain movies that are “very attractive to the audience but too few for our weekly programme.” With further deals with distributors including Mad Solutions, though successful, Darb 1718 screenings are no longer free.

Alternative screening scions disagree about making people pay. For Yahia, “I cannot download or steal a movie off the Internet and then get paid for screening it. Any public screening should be licensed.” But Saleh feels those who put in time and effort to organise the screenings should be paid regardless: “Even if we are screening a movie in a film club, the audience should pay a symbolic amount. It is very difficult in such economic circumstances to do volunteer work.”

Still, screenings at such NGOs as Al-Nahda Association, the Egyptian Film Critics Association, the Egyptian Catholic Centre and Daal cultural centre, movie night is traditionally free.

According to Sayed Abul-Ezz, the coordinator of Daal Cinema, with screenings taking place in an apartment with wood chairs and a projector, “a license is not a necessity”. The value of an alternative screening space will always exceed any financial outcome, he insists. But since “most of our movies are classics or could be found online” and “we only have room for a very small audience”, the Daal model cannot work everywhere.

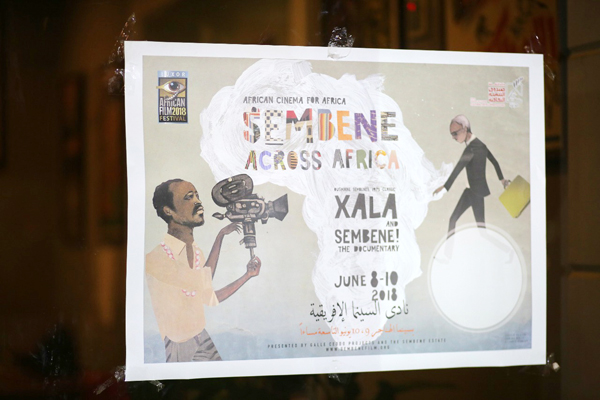

A poster from The African Cinema Club (Photo: Al Ahram Weekly)

Ayman, for example, says Zawya screenings should have both a screening and a censorship license: “Even Egyptian classics routinely screened on national television still require a censorship licence. Still, though we always recommend that movie clubs should have licenses especially if they are screening Zawya films, it’s not fair to be strict with the smaller clubs.”

Though rare, incidents such as the cancelling by security of a screening of Tarik Saleh’s The Nile Hilton Incident (2017) at the Balcon Lounge restaurant in Heliopolis do happen. In this case the censor had refused to license the film to be screened at the 10th Panorama of the European Film.

Abul-Ezz, however, is not too worried. It was a sensitive film and it had been on the security radar for its own sake. “We cannot guarantee this will never happen but we are taking the risk to be keep these spaces running without too much complication.”

As Ahmed Zidan, the owner of Room café and art space in Garden City says, even movies easily available on the Internet for free home viewing attract an audience. Screenings are for free, Zidan explains, but there is a minimum charge on orders. The café has room enough for 30 people. And though the weekly screenings are not as profitable as live concerts, he feels they are significant.

“I love cinema,” Zidan says. “I was always part of a home movie night programme. People need the experience of sharing and discussing a movie, speaking their mind in a safe public space. Others may not have access to private screening spaces for various reasons. But I also believe such initiatives by encouraging greater and wider viewing will positively impact the film industry.”

For film scholar Nour Al-Safouri who is based on field work in seven governorates has just completed a paper, “Observing the cinema audience: Egypt” in cooperation with the Network of Arab Alternative Screens, “It was very interesting to find out that film clubs and other alternative screening spaces are attractive to many young people especially in governorates which have no cinemas although they can watch the same movies at home online.” The reason she gives is that, for the 18-40 age bracket, movie going is part of a pattern of activities that involves going out with others.

“Cineclubs,” Al-Safouri says, “had a very important role in the 1960s and 1970s although these tended to be politically and ideologically motivated events. Now it’s about examining freedom of expression in a safe public space and exploring the wider world. Whether such spaces can generate an alternative social awareness depends on the motives behind establishing them. As much as they break the dominant patterns of circulation and cater to aspiring filmmakers, they may well be the seed of truly great things. But studying them in depth is the only way to guarantee their sustainability.”

This article was first published in Al Ahram Weekly

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

Short link: