I have mentioned before that the British Lord Carnarvon, who funded the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, and Howard Carter, who discovered it, had plans as to what they believed would happen with the treasure from the tomb of Tutankhamun. They started to excavate the tomb, officially opened it, and began taking the treasures out of the tomb after the discovery in early November 1922.

During this time, Carnarvon and Carter felt sure that half the treasure would be in the hands of Carnarvon to do what he wanted with it, either to sell it or keep the objects. Being sure of this, the English lord began to act without taking into account the opinions of anyone in the Egyptian government.

He sold the exclusive rights for publication about the discovery to the London Times for 5,000 pounds sterling, as if the tomb had been found under his bed in his home in England, Highclere Castle. But it seems that God was on the side of the Egyptians and the treasure because on 5 April 1923 Carnarvon died. Carter was shocked by the news. Without Carnarvon, it seemed that he no longer had the power to take the artefacts and would lose his fight to see any division of the spoils from the tomb.

Before we close the page of Carnarvon and continue the story with Carter, I should mention that Carnarvon had plans to be the only person featuring in the news about the discovery of the tomb, as if he was the one who had found the tomb and it had been his idea to search for the tomb of Tutankhamun. Carnarvon was afraid that his role in the media coverage would be only as the one who had paid for the discovery. Because of this attitude, he began to deal badly with Carter. He wanted to take Carter out of the narrative that was spreading across the world, but you cannot take the discoverer out of the tale of discovery. Carnarvon thus had to accept Carter and deal with him, but he was not happy about it.

The first excavation season ended a few days after the death of Carnarvon in early 1923. Carter then went to England for the summer. During this time, he was no doubt thinking about how he could possibly keep the treasure and honour his own name through it. The first step was to keep the rights of the discovery in the Carnarvon family, now under Lady Evelyn, the daughter of Carnarvon. She also renewed the contracts with the London Times for another season.

In October 1924, Carter returned to Egypt to start the second season of clearing the tomb. It was at this point that trouble started between Carter and the Egyptian government. Carter refused to allow a team of Egyptian officials to visit the tomb. At the same time, he permitted his assistants and his friends to enter it. Carter’s actions were biased by his imperialist attitude that came from his English heritage, despite coming from a poor family with little education.

Carter first opened the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun to see the mummy on 12 February 1924. He was able to raise the lid of the stone sarcophagus, hanging it from the ceiling with ropes, and inside he found three inner coffins. The photograph of the lid of the sarcophagus hanging from the ceiling was one of the most dramatic photographs by Harry Burton, the official photographer of the expedition. This image was seen by millions of people, showing the golden discovery.

Meanwhile, Morcos Pasha Hanna became Egypt’s minister of public works, and the Antiquities Department was under the authority of this ministry. Hanna hated the English and fought their power in Egypt. On 19 January 1924, he took the opportunity to dismiss Carter from Egypt. To explain the hatred that Hanna had for the English, one must understand that Hanna was a young intellectual who had studied law in Paris. He then came back to Egypt to work for his country. He was a nationalist and a member of the Wafd Party of independence leader Saad Zaghloul Pasha. The latter was exiled to the island of Malta and then to the Seychelles by the British, who also arrested Hanna and six others.

Hanna was sent to an English military court, where the decision was made that he and the others should be put to death. Through a miracle, the sentence was reduced to seven years in jail and a fee of LE5,000. Hanna left jail after he had spent only eight months incarcerated with criminals. During his sentence, the tomb of Tutankhamun was found, and Carnarvon died. Then the ministry of Abdel-Khalek Tharwat, who was on the side of the English, fell.

Morcos Hanna Pasha became minister of public works in January 1924 as a member of the first ministry of the Wafd Party headed by Saad Zaghloul Pasha.

OPENING THE SARCOPHAGUS: In January 1924, Carter was preparing to open the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun that had been found in the tomb.

Hanna heard how Carter had treated the Egyptian officials and that he was going to permit the wives of his expedition crew to visit. He ordered Pierre Lacau, the then director of antiquities, to close the tomb and take the keys from Carter. He even appointed police to accompany Lacau to make sure that the order was carried out. Carter was furious, considering this to be an insult. He closed the tomb but refused to hand over the keys. He also wrote an angry statement about the incident and tacked it to the door of the Winter Palace Hotel on the East Bank of the Nile at Luxor.

The London Times began to attack Hanna as an enemy of the English, but Hanna was beloved by the Egyptians. Hanna was a Copt, and he led the Christian population of Egypt in preserving the dignity of Tutankhamun through his dismissal of Carter. The entire country praised his actions, taking to the streets and shouting, “Vive the Minister of Tut.”

Carter then came to Cairo to start a court case against the Egyptian government. He insisted that the Carnarvon family be allowed to take a share of the objects from the tomb. The court could not come to a decision. Disappointed and feeling that he would not be allowed to take anything, he went to England and the US to give lectures about the tomb.

On 20 November 1924, a group of young people then shot up the car of the then English governor-general of Sudan Sir Lee Stack. He was leaving the Ministry of Defence in Cairo and heading home to Zamalek at the time. The next day, it was announced that he had died due to injuries sustained in the attack. The cabinet of Saad Zaghoul was placed in a bad position, and many of them resigned, Hanna among them. This major enemy of the English, and specifically of Carter, was now out of the picture. England began to use the death of Stack to expand its power in Egypt. The new cabinet tried to make peace with the English and looked at the problems that they had had with the previous ministry. One of these was the struggle over the rights to the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The new cabinet decided to ask Carter to return to Egypt in the presence of Lacau and Lady Carnarvon. They finally came to an agreement. Carter and Lady Carnarvon would withdraw their court cases against the Egyptian government. They would also write a letter stating that they had no right to take any objects from the tomb. In return, the government gave Lady Carnarvon 36,000 pounds sterling, the amount spent by Lord Carnarvon on the discovery of the tomb. After this payment, the commission was cancelled. Carter and his team were appointed to work under the Department of Antiquities as he finished the clearing of the tomb. This ended the struggle over the tomb of Tutankhamun, with the Egyptian government paying the costs to finish clearing it.

But now we come to an important question: Did Carter steal from the tomb of Tutankhamun? We know that he found 5,398 objects inside it, all of which had been stored in a very small tomb for over 3,000 years. As explained before, the relationship between Carter and the Egyptian government had reached the courts, which led to speculation as to how far he would go for what he felt was his share. A great deal has been written against Carter in this regard, including a recent article in the UK Guardian newspaper before the anniversary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun that suggested that Carter stole from the tomb. Did he keep objects from it for himself?

I do not really want to accuse a man who made the most important discovery in history. I have to be fair also in not saying anything against him because he cannot defend himself. But here I will lay out the evidence for readers to make their own decision.

TAKING FROM THE TOMB? People began to have suspicions against Carter and Carnarvon because it was believed that they had entered the tomb alone before the official opening.

If this had happened, it would have occurred between the arrival of Carnarvon at Luxor and before his death in April 1923. We do not have any evidence that they entered the tomb at this time, but one Egyptian newspaper published comments by Alfred Lucas, a member of Carter’s team responsible for the conservation of the tomb and its objects, saying that Carter entered the burial chamber twice. The newspapers said that the door was sealed with modern stone and mortar, indicating that Carter had closed the opening after having entered it.

We cannot say if this story is true or not, especially because we know that there was a great hatred of Carter in the Egyptian press at the time. He was portrayed as a snob who wanted to steal the treasures of Egypt’s ancestors.

We also have one truly documented “accident” that also led the Egyptians to believe that Carter stole from the treasures of the tomb. The story begins when the Egyptian government appointed a committee of officials from the Antiquities Department to oversee the inventory of the items from the tomb of Tutankhamun. The committee entered KV4, which was being used by Carter and his team for eating meals and for temporary storage. The tomb was made for Ramses XI but was never finished. There is a famous photograph of Carter and his team eating inside the tomb and being served by waiters from the Winter Palace Hotel.

To come back to the story, the Egyptian committee was there to review the items that came out of the tomb and connect those items with the registry book and diary of Carter. At first, everything went well, and all the objects fitted with the official register. But then one member of the committee found a small box that was ready to be sent out of the country. It was the type of box used to send objects out of Egypt not the type of box used for transfers to Cairo. We do not know the official’s name, but he gave the head of the committee the closed box.

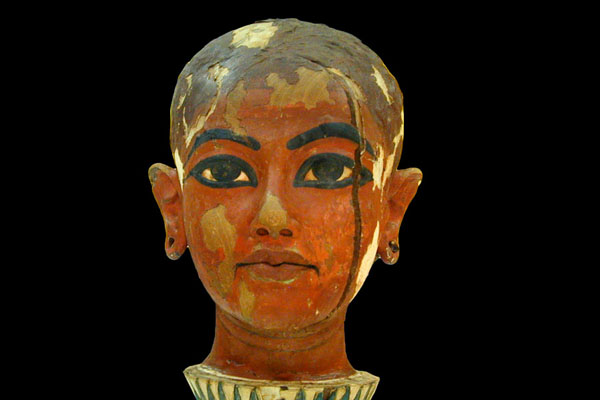

Some people say that they asked Carter about the box, and that he said he did not remember what was in it. Others say that Carter was not even in Egypt at the time but was lecturing abroad. When the committee opened the box, inside was one of the most beautiful objects from the tomb. It was stunning wooden carving of the head of Tutankhamun on top of a lotus flower, covered with gypsum and painted in bright colours. Some Egyptologists believe that this rare object shows Tutankhamun as the god Nefertem coming out of a lotus flower with the new day in a sunrise for this great civilisation.

The committee was astonished. They took the object out of the case, put it on a table, and began to examine it. They studied Carter’s notes and could not find any mention of the object. They also reviewed the official registry, and there was no description which matched the object. This means that this object had nothing written about it with the other objects of the tomb. When they asked Carter with this and about how this item could be in a box without a registry number, he mentioned that he had found the piece inside the descending passage that led to the tomb.

Was he saying that the piece was not from the treasure of the tomb and should not be included in the tomb’s contents? Or that he wanted to indicate that there was evidence of previous entries to the tomb, thereby making the tomb not “intact”? Or was he simply trying to come up with an excuse as to why the object was not registered, knowing that it should have been?

Another story that is still a mystery is that of the head of the mummy of Tutankhamun himself. All the photographs of the mummy by Burton, the official photographer of the tomb, show that the embalmers had put a skull cap or headdress on the head of the king. This piece was made of golden beads and other precious stones and placed on the head underneath the golden mask. But this object has not been found in the tomb contents, and we do not know where the skull cap of Tutankhamun disappeared to.

Another curious incident came to my attention in 2010 when I was head of antiquities in Egypt. I received a letter from Tom Campbell, the then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, stating that two members of its Egyptology Department were studying 19 objects in their storerooms that they were sure were connected to Carter. Some of these objects were acquired from the daughter of Carter’s sister after he died in 1939. They looked at the will of Carter and found that the daughter of his sister indeed inherited these objects from him. They had been in Carter’s house in Luxor before being inherited by Carter’s niece.

These objects were identified by Burton, who then worked for the museum, as having come from the tomb of Tutankhamun without authorisation. He wanted the matter to remain discreet, so the 19 objects mentioned were sent through Carter’s niece to the Metropolitan Museum in 1940, rather than to the Cairo Museum where an international incident may have followed.

I said that these objects must be returned to Egypt. I talked to Campbell and Museum official Dorothea Arnold, who agreed to hold a press conference about the matter. We announced that these 19 pieces taken from the tomb would come back to Egypt after a six-month exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The objects were returned in July 2011.

CARTER’S INVOLVEMENT: The last story comes from the article that the Guardian published last August accusing Carter of stealing objects from the tomb.

It seems to me that there is a connection between the publication of this accusation and the anniversary celebrations of Tutankhamun. The article discusses a letter to Carter from Sir Alan Gardiner, a famous philologist and member of the expedition excavating the tomb. His role was to translate the texts on objects and the walls of tombs.

The story begins with Carter having a habit of giving gifts to friends. He gave Gardiner an amulet in appreciation of the work he had done, saying specifically that it was not from the tomb of Tutankhamun. However, Gardiner showed the amulet to Rex Engelbach, the British director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo at the time, who said that it was made from the same material as the amulets in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Gardiner felt that it had to be an object from the tomb and wrote to Carter saying that the latter had put him in a very difficult position. He added that he did not tell Engelbach that the amulet was from Carter. The article in the Guardian published this letter, which had already been published in Egyptologist Bob Brier’s book Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World.

This is the story of Carter and his involvement with the objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun. I leave it to the reader to decide what happened during the discovery of the tomb. However, we cannot forget the great work that Carter did in restoring and excavating the objects. Today, we must write the whole truth about everyone involved, while giving our opinions of Carter as an archaeologist and emphasising that he did an excellent job in the clearing of the tomb.

When I wrote a book in which I imagined I had made the discovery myself, I wrote that I would not have done anything better in 2020 than Carter had done a century ago. Carter did a very good job in spite of the fact that he was not formally educated in archaeology. Life taught him, and he was trained by British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie to be an excellent archaeologist. It is up to you as a reader to decide the rest.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 17 November, 2022 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

Short link: