This child is not the only one who has endured such anguish. Thousands of unaccompanied children have been forced to abandon their parents and hometowns in order to reach a destination chosen by smugglers.

According to UNICEF estimates in September 2021 more than 33 million children worldwide have been forcibly displaced at the end of 2020 This number includes some 11.8 million child refugees and 1.3 million asylum-seeking children most of them had to embark on risky journeys to reach a safe haven.

During their arduous journey, these children are subjected to detention at the border for periods that exceed the legal limits, as well as various forms of violence, torture, and intimidation, and a large number of them are the victims of sexual assault.

According to some international organisations, unaccompanied children are the most vulnerable group of refugees. Reports reveal that they lack safety and security and are experiencing food, housing, health, and education crises.

Over the course of a year-and-a-half of research into the living conditions of this forgotten group, investigators documented testimonies with video interviews and audio recordings, revealing the hidden world of these children uprooted from African countries like Somalia, Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan, and Chad.

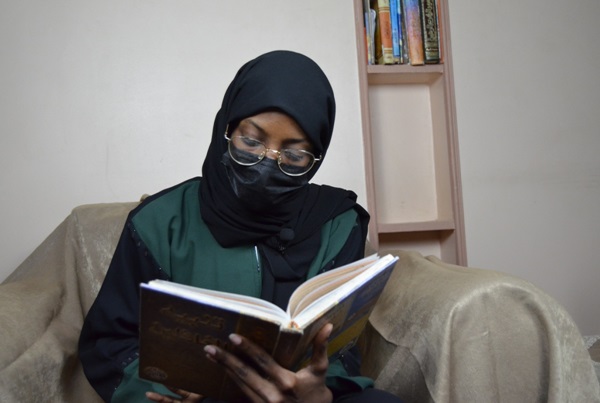

Tahani: The girl who resents her daughter, a product of rape

"I abhor my daughter. When I look at her, I feel tethered... Sometimes I wish I could go back to the moment she was born and toss her away. She constantly reminds me of things I want to forget,” 17-year-old Tahani said while recounting the assault she experienced two years earlier, which resulted in her having an unwanted child and suffering severe psychological distress.

Tahani (a pseudonym), a Sudanese girl who arrived in Egypt without an escort, was pushed by her mother to pretend to be three years older so she could leave the country legally. Her mother hoped to follow her later.

Tahani was raped in Cairo.

"I am always followed by people's gaze because of this incident, even though I attempted to defend myself and couldn't do anything."

Tahani says she was tricked by a Sudanese man who rang her apartment doorbell and told her he wanted to read the gas meter, but instead sexually assaulted her.

Tahani was living at the time with a Sudanese woman she had met upon her arrival in Cairo.

"I wanted to tell her about the incident, but I was terrified she wouldn't believe me and would kick me out of the apartment. Now I'm terrified of the stares of people near me because I feel they think I'm a criminal, not a victim."

According to the statistics recorded by the UNHCR on Egypt’s response plan to support refugees, during the month of October 2019, 30 incidents of sexual violence were committed against children, 23 girls and seven boys: 16 cases of rape, 10 sexual assaults, and four cases of abuse and harassment.

Tahani reported the incident after her daughter's birth, and the UNHCR assigned her a lawyer, which allowed her to acquire a birth certificate for the baby girl, who was given a random name: "They told me we would choose a name for her father."

Tahani's mother, Salma Abdel-Razek (a pseudonym), managed to undergo an arduous voyage with smugglers who helped her cross the Egyptian border. She found her daughter, but was shocked to find her pregnant with the child of someone she does not know.

"My daughter did not discover her pregnancy right away. She did not associate the interruption of her period with the incident she experienced. She had no idea that her period would cease during pregnancy," Salma said.

“I found that she was not ready to deal with my granddaughter, so I took full responsibility and registered the child in my file at the UNHCR. I had to take the baby with me to work for fear that she would be abused by her mother.”

She said her daughter is going to a psychiatrist named Gloria from the CRS organisation, who is working to psychologically rehabilitate her, but she refused to interact with the UNHCR's Bastak Foundation because the psychiatrist responsible for her case was Sudanese.

Salma is compelled to relocate every five months for fear of being caught by the people in Sudan who forced her to flee her country.

"I reside in an area hidden from the Sudanese, and if I want to meet one of my friends, I suggest a faraway place. I am also terrified that my daughter's uncles will find out where we are and take her away from me, since Sudanese law gives them that right," Salma says.

‘Good Accompany’: A program to help children integrate

Maha Tabiq, a Sudanese woman who has lived in Egypt for 17 years, established the Good Accompany initiative six years ago. The initiative, which comprises women from Sudan and Eritrea, helps unaccompanied refugee children integrate into society and puts them in contact with international organisations that can help them settle.

Tabiq says that the idea for the initiative crystallised during coffee gatherings, which involved more than 50 women discussing different issues.

"Most of the unaccompanied children we took care of were from Eritrea, Sudan, and Chad. We provided them with accommodation at our association. We also contacted Save the Children and Bastak, and many cases were addressed and resettled," she said.

Tabiq said that they were able to save many children who were contemplating suicide, and that the Bastak group also helped many children living under difficult circumstances.

Tabiq shared an incident that affected her deeply, involving one of the cases handled by the organisation.

"A girl was tricked by a broker who promised her that he had a job for her that paid a huge amount, and when she went with him, she found herself in a flat where three young guys lived.

“The Eritrean child was their hostage, and they raped her many times, and they threatened her with death if she thought of escaping. The girl's condition worsened, which made them get rid of her by throwing her out into the street, where she died from blood loss. A forensic investigation revealed that she had been suffering from a pregnancy outside of the womb.”

Since 2017, Tabiq has decided not to listen to the stories of unaccompanied children and to limit her role to communicating with organisations, coordinating between them and the cases they find. She found that she was deeply affected by these stories and underwent psychological rehabilitation as a result. She remembers her own childhood crisis as a refugee.

Reem Abdel-Hamid, External Relations Officer at the UNHCR office in Cairo, says that nearly 37 percent of all refugees and asylum seekers registered in Egypt are children, including 4,067 separated or unaccompanied children.

The unaccompanied children are from Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Syria, according to a UNHCR official in charge of external contacts.

Reem said that the UNHCR's office in Egypt is one of the largest resettlement initiatives, as it works to increase resettlement opportunities for all refugees. Places for resettlement are very limited, as each country sets special standards for those whom it wishes to host.

Fatma: 14-year-old in diapers… and with a bullet in the leg

Fatma Hussein, a 14-year-old Somali girl, lives in a modest apartment in 6 October City with three other girls from Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia, all of whom entered Egypt by way of irregular migration.

Fatma was the youngest of the girls in the flat. Because she could not speak Arabic or English, she was isolated from her flatmates most of the time.

Fatma suffered from significant psychological problems. The struggles she encountered on her voyage from Mogadishu to Cairo left her with trauma that is difficult to erase. She suffered from urinary incontinence as a result, so she had to allocate a part of her expenses for diapers.

Fatma's condition has somewhat improved, but she is still unable to pay for treatment for a gunshot wound she suffered during her trip to Egypt, which makes it difficult for her to move.

"When I sought aid from the UNHCR for the treatment for my leg, I found no one to help me,” Fatma said.

Education is not useful for Fatma because the curricula are in a language she cannot understand. Finding a job is also difficult for her.

Despite her young age and health problems, she continues to look for a source of income to get the funds she needs to live, but she is unable to find a suitable opportunity.

Since Fatma cannot speak Arabic, she spoke to us with the assistance of her sister, Jawaher.

Jawaher arrived at the Egyptian border six years ago after having lived in harsh conditions in her home country.

Jawaher is Fatma's older sister, and by a stroke of luck they reconnected after spending years apart.

"Fatma was detained as a result of my actions, and she suffered during her travel to Egypt as a result of her serious injury, which rendered her unable to walk normally. I'm trying to make it up to her, so I work 16 hours a day to meet our needs," Jawaher explains.

Jawahar's reunion with her sister was entirely coincidental. A few months ago, she received a phone call from a friend telling her that a group of Somali immigrants was living in Nasr City’s Souq El-Sayarat area, including a girl from her village. Jawaher hesitantly went, only to find herself face-to-face with her younger sister.

"When I found myself in front of my sister, I couldn't believe it. I gave her a big embrace. She was sobbing so hard that she couldn't speak," Jawaher recounted.

"My last contact with my family was in March 2016. I was in South Sudan at that time, and contact with them had been broken off, and the home phone number was no longer available, so I didn't expect this coincidence."

Jawaher returns to talking about her sister, saying, "Fatma suffered greatly as a result of the trip, with the most terrible aspect for me being that I forced her to wear diapers. It bothers her, but I can't allow her to pee on herself."

"My sister used to urinate only while asleep. She would wake up and find the bed wet, but then she started suffering from this problem throughout the day."

Jawaher says that more than half of the aid from the UNHCR is spent on diapers, since Fatma consumes two large-sized packets for EGP 500 every month.

"We barely get EGP 900 per month from the UNHCR. Despite the fact that she needs a knee operation, which has caused her tremendous distress. She is not receiving due care," according to Jawaher.

"Fatma used to tell me everything that bothers her, but there has been a change in her personality recently, as she tends to isolate and stay longer in her room."

Jawaher has had Fatma undergo numerous medical tests, including brain and chest scans and blood tests, for which she was able to secure UNHCR funding.

Fatma herself shared more details about her journey.

"I did not think that my older sister was still alive. I had given up hope of ever finding her," she said.

“The Al-Shabaab [terrorist group] broke into our home, beat my father and mother, and kidnapped all of us. They whipped us every morning because they were searching for Jawaher and demanded we tell them where she was, even though we had no idea,” according to Fatma.

"I was able to flee with the assistance of one of the female guards. She sympathised with me since she, too, had been kidnapped before Al-Shabaab chose her to work for them."

Fatma then headed to Sudan, and she faced great difficulties during the trip, including getting shot in the leg.

“The best period of my trip was when I arrived in Sudan. I got to know four girls from Somalia studying there, including a doctor, a teacher, and an engineer.

I was suffering from health crises, they were taking care of me, and Halima, the doctor, was following my treatment and giving me injections at home. I was learning many things from them, but now I am unable to learn, and I cannot become a doctor like Halima, as I had wished.”

Fatma lived in Khartoum for a year-and-a-half before her companions decided to return to Mogadishu when the Sudanese revolution broke out, and because it was impossible for the child to return to her home country, she moved on to Egypt.

Jawaher picked up the conversation, saying, "My sister was attached to them, and I hope to find a way to contact them to thank them for the care they provided her.They took care of all the expenses during the time she spent with them."

"My sister then decided to escape to Egypt. This was a better option than returning to Somalia because Al-Shabaab would not let her live; they control everything. They can disconnect the internet from the village whenever they want and reconnect it whenever they want."

The suffering of these children –from sexual exploitation and abuse to the lack of access to food, shelter, health, and education – continues amid silence and disregard from international organisations.

Exploitation of the foster family system

Samira Ibrahim, an Eritrean, welcomed us into the poorly furnished two-room flat where she lived with her six children and two Eritrean girls, Aya and Razan (10 and 12 years old), who had lost their parents and came to Egypt in a difficult voyage with human smugglers.

"I am aware that many families exploit unaccompanied children in order to gain UNHCR financial aid, but I consider the two girls as my children and provide them with the protection that I did not have," Ibrahim said, stressing that she is aware of the abuses to which child refugees are subjected, which frequently include sexual assaults, and that this was what motivated her to care for the two children.

"The two girls were forced to obey the orders of the smugglers and arrived in Egypt after a rough journey where they were exposed to torture and long walks," Ibrahim explains, adding that the two girls are refusing to talk about their ordeal.

Razan and Aya have received no financial support from the UNHCR so far, while Ibrahim, who has obtained a Refugee Registration Card (Blue Card) from the UNHCR, is awaiting an opportunity to move to Europe and is also looking for another home for the two girls.

Malaz, 8, Muhammad, 6, Fatma, 3, and Muhannad, one-and-a-half, are Sudanese children whose mother passed away and left them without a breadwinner. They have found themselves living with a new family that includes seven other children who are taken care of by a Sudanese woman named Howaida Al-Hajj.

"I volunteered with the UNHCR to take them and give them care because they had no relatives, and I assigned them a room among my children. I now have 11 children," Al-Hajj said.

Al-Hajj contacted the St Andrews organisation and informed them that there were four children who needed care and that she wanted to register them with the programme.

"The organisation asked me why I wanted the children to join my family, so I told them that children have the right to a mother and a family to care for them," Al-Hajj explains.

The Sudanese woman says that Malaz asked to enrol in school because she wanted to learn to read and write, and that she was the only one who refused to call her "mum" instead of "aunt."

“I now get assistance from St Andrews and Caritas,” Howayda explains. “St Andrews provides me coupons for food, rent, and diapers, but I work long hours to make money, and as a result, I leave my children the majority of the day.

According to refugee lawyer Ashraf Milad, "families who support unaccompanied children receive financial aid in exchange for care, and I know more than one family that has adopted many children for this reason."

Milad explains this is because there are many unaccompanied child refugees who flocked to Egypt amid the mass displacements of Eritreans and Ethiopians that began in 2008.

"The first agency that deals with unaccompanied children is the UNHCR, through an officer responsible for child protection,” Milad says.

"The UNHCR investigates the children's families, and when it is confirmed that they are unaccompanied, the sponsorship procedure is often employed, where they are incorporated into families who hail from the same tribes [as the children]," he explains.

Milad emphasised that these protocols are tightly enforced, since there have been situations where gangs who sell organs have exploited these children.

Milad says that some families in countries in the global south illegally send their children to safe and stable countries, and when the child is accepted, they submit a request to bring the family to live with them. Milad says these families have no problem exposing the child to danger in exchange for moving to a better life.

Milad believes that the problem with these youngsters is that many of them are unable to obtain aid, and that they "slip through the cracks."

Yasser Farraj, director of El-Haq Office, which specialises in African refugee issues, points out that there is no legislation regarding unaccompanied children in particular, but it is possible to classify this category under "street children."

"Egyptian law supports children who do not have families through state-owned social institutions,” Farraj says.

Egypt is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol, as well as to the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, but under a framework agreement signed in 1954, the Egyptian government does not provide full access to public services to refugees and asylum-seekers including jobs, housing, health, and education. The UNHCR and its partners try provide the essential needs.

According to the head of El-Haq Office for Legal Support for Refugees, St Andrews is one of the UNHCR's partner organisations with a special section for caring for unaccompanied children.

Farraj said that some foster families intentionally disrupt the process of children becoming reunited with their original families because they do not want to lose the financial support they receive.

Farraj suggested establishing an institution to provide unaccompanied children with free housing, education, health services, and other essentials, saying he believes the UNHCR and partner organisations, if they work together, would be able to put such a proposal into action.

Some refugees falsely claim their children are unaccompanied

Amir Khaled, a Sudanese national and secretary of the Strong Wings organisation, says that some refugees renounce their children and claim they are unaccompanied, and that this deception frequently takes place through the UNHCR.

The problem, according to Khaled, is that the commission works with community-based organizations (CBOs) that are picked on an ethnic and tribal basis, making them biased.

These issues eventually lead to the UNHCR receiving inaccurate information about the cases of unaccompanied children, Khaled says.

He emphasised the importance of the UNHCR adopting a new mechanism to determine whether children are, in fact, unaccompanied, as well as having skilled and qualified people who can interact effectively with the sub-Saharan African groups residing in Egypt.

Khaled – who has spent 10 years involved with the refugee issue –says there is also a need for using mental health professionals who have experience in dealing with African societies.

Waiting for a reunion

On the eastern bank of the Nile in Maadi, Cairo, the Chadian girl Ramaz Mohamed (a pseudonym) waited for her turn to meet with officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), after receiving information that her siblings residing in Canada had been reached.

The 17-year-old Ramaz had not thought she would ever see her sisters, so when she was at the ICRC headquarters, she made a point of writing down what happened in her notebook.

"You can now talk to your sisters," an ICRC employee told Ramaz, who recounted her experience for us.

"I'm OK, don't worry," she told her sisters, sobbing throughout the phone call, which lasted for a few minutes.

Ramaz was responding to questions from her sisters Bushra and Salana about her health and how she was being treated by her foster family in Cairo.

"It was the first time I had spoken to them... and the first time I felt family affection," she says.

Her moment of happiness was cut short, however, when a Red Cross employee told her that it would be difficult for the ICRC to help reunite her with her two sisters through the Restoring Family Links programme, and that her case would be referred to the UNHCR.

This meeting was in early January 2021, and Ramaz has not yet found a way to become reunited with her two sisters, despite the fact that the Red Cross has located them and the UNHCR is aware that she has been staying with a foster family for more than a year.

Ramaz’s ordeal began when her father wanted her to marry his 60-year-old friend. Ramaz belongs to a Chadian tribe where men determine the fate of girls when it comes to marriage, and decisions taken by men must be obeyed without discussion.

Ramaz’s aunt, who had been taking care of Ramaz since her father separated from her mother, told the girl to pretend to agree to the marriage until an opportunity presented itself for her to flee to Egypt.

"My mother was divorced when I was three years old, then she left me with my father and travelled to Sudan. I heard from my aunt that I had two sisters in Canada, but I only saw my father, and I could not bear to stay with him, especially after he tried to force me to marry a man in his sixties," the girl says.

“Are all fathers cruel like my father?” Ramaz pondered while talking to us, and without waiting for an answer, she reproached her father: “Dad, you should have loved your daughter more than your tribe.”

Upon her arrival in Egypt, Ramaz met her aunt's friend, who lives in the Haram area in Giza and with whom the aunt had arranged for Ramaz to live. The friend had also agreed to register Ramaz with the UNHCR with the hope that she can reach her sisters, about whom she new nothing other than that they lived in Canada.

“We cannot find anything from the little information [you have given us],” an ICRC employee told Ramaz during her first interview.

Ramaz says that during the first three months with her aunt's friend, she was not made to feel uncomfortable or burdensome, but then the attitude began to change gradually, and she has no idea why.

“She started preventing me from contacting my aunt, and she started treating me like her maid. I remember her waking me up abruptly after two hours or less of sleep, and asking me to arrange and clean the apartment,” she said, describing her treatment as that of a “prisoner.”

"I did not get any personal expenses from her, but in return she would take the aid I received from the UNHCR, and then tell me it was payment for me staying. I was getting 400 pounds for a food basket and 900 pounds a month from Caritas."

Ramaz escaped with the help of a friend of the woman's daughter, who sympathised with her and took her to a new household in the Hadayak Maadi area.

Ramaz received treatment she did not expect from the new family, who treated her like one of their own and motivated her to continue her education.

Ramaz had been studying at a school called King Faisal in Chad, where she preferred the Arabic curriculum over the French.When she wanted to finish her education in Cairo by enrolling in a Sudanese school, she had to enrol at a grade three years below her age due to a lack of certificates proving her academic level, so she had to start from the eighth year of the Sudanese educational system.

Unaccompanied children are our top priority: Red Cross

Leo Brueser, deputy head of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Cairo Delegation for Protection, says that the ICRC helps establish communication between family members who have been separated due to armed conflict, natural disasters, or on migration routes, adding that “unaccompanied minors are the most vulnerable group we strive to help, and they are our first priority.”

“Depending on the country and situation, children who are unaccompanied, separated from loved ones, or otherwise affected by armed conflict, may receive various forms of assistance from the ICRC, either directly or through one of our partners,” Brueser explains.

“The ICRC has also expanded its activities in recent years to help children gain access to education, whether they are unaccompanied or not,” he said.

Brueser added that in some countries, the ICRC collaborates with international and local NGOs to ensure that unaccompanied children have access to shelter while the search for their relatives is ongoing.

“While we believe that, as a general rule, the best interest of children is served by reuniting them with adult family members, there may be exceptions, in which case we work closely with organisations better suited than the ICRC to conduct best interest determinations,” Brueser said.

“There are cases where the ICRC will either contribute to the cost of lodging minors while the search for their loved ones continue, and will provide assistance prior to the reunification, both to the children and the family,” Brueser said, adding that limited support is also provided after a reunification “to facilitate reintegration or [provide] dignified living conditions.”

Concerning unaccompanied African children receiving Red Cross assistance, “it is difficult to issue figures on the number of African children receiving support around the world, whether in Africa or other countries,” Brueser said.

"In 2019, the last year for which this data is available, the ICRC reunited 897 people with their families, including 729 unaccompanied or separated children.”

Education for unaccompanied children

Mohamed Mannallah, a Sudanese national, has extensive experience in assisting refugees. He has volunteered to help refugees for over 10 years, during which he has worked with international and local organizations including the International Organisation for Migration and Save the Children.

Mannallah has focused his attention on the issue of educating African children who have little access to education. His first step was to establish the Ard El-Lewa Association, as well as schools to educate unaccompanied children for free.

Mannallah says that 90 percent of these children are not native Arabic speakers, which makes it more difficult for them to integrate into the educational field. So, the Ard El-Lewa Association is devoted to teaching these children Arabic.

"These children entered Egypt illegally, and they do not have identification papers or certificates to determine their level of education. There are also differences [between countries] in educational curricula," Mannallah said.

"I established a school in 2010. It consisted of one classroom, which I named Opportunity, and it was a simple outlet for teaching these children Arabic and mathematics. I now own four branches in Greater Cairo, where more than 1,000 students are studying,” he revealed.

“We now have an integrated educational centre, and we collaborate with the Red Cross in a monthly bulletin, and we recently convinced the Sudanese embassy and the Education Department of the UNHCR to allow unaccompanied children to take the Sudanese certificate exam,” Mannallah said.

"The Sudanese embassy also provides tests for non-Sudanese, which has contributed to providing services to Eritreans, Somalis, and students of other nationalities," Mannallah continued.

The Sudanese embassy offers Sudanese certificate exams for $100 for Sudanese nationals and $250 for others, he said.

"We act as a link between the Sudanese embassy and unaccompanied students from Sudan and other African countries, "Mannallah said.

Among the stories that prompted Mannallah to dedicate much of his time to helping unaccompanied children was that of the Eritrean child Mayar Musa (a pseudonym).

"I used to hear many distressing stories about the experiences these children face every day, but the experience of Mayar, who suffered greatly after escaping Eritrea to flee conscription, struck me personally."

The child was only 14 when she suddenly found herself alone without a family or a home.

Mayar, who had resorted to travelling illegally, had no choice but to turn to the UNHCR, which in turn sent her to the Ard El-Lewa Centre.

“The girl spoke only Eritrean and memorised some words in Arabic, and the effects of psychological shock filled her face. She did not stop crying whenever she recalled her suffering, and despite my attempts to talk to her, she remained silent for a while. The first time I heard her speak was when she asked me to provide her with a job after her friends had migrated across the sea, and she could not find adequate housing or money to live on her own.”

"I did everything I could to help her and gain her trust. I was surprised when she told me one day that she had gotten a job with a doctor who works at Cairo University and has two young children who can live with her and who she can help raise," Mannallah states

What bothered Mayar greatly was her desire to return to her homeland and live with her family again, which would not be easy because Eritrea makes it difficult for anybody to return after fleeing illegally.

“I tried to contact her family, but she found an opportunity… and ended up travelling to America through legal means.”

‘The only thing I remember of Sudan is the sound of gunfire’

Nihal Khalil, a 15-year-old Sudanese girl, was forced to travel with smugglers without anyone from her family. She fled her country due to the bloodshed in Darfur and the escalation of fighting in the area where her family lives.

Despite having lived in Egypt for three years, the small girl knows nothing about her mother, father, or her three siblings.

Nihal met with us in a small apartment in the Faisal area, where she lives with a woman and a child she met after arriving in Cairo.

“All I remember from the moment I ran away from my city was the sounds of shooting and the screams of my family, and without the help of some neighbours, my fate would have been different."

Nihal left South Darfur for Khartoum, then to Halfa, and then Cairo.

"I want to learn, but the lady I live with does not provide for my needs, and I feel that there are many things I am missing. I do not live like other children," she says.

"I finished the eighth year of education, but tuition fees are expensive, and taking exams requires having dollars," she added.

The Sudanese girl says she finds it difficult to integrate into Egyptian society, and that she is sometimes bullied because of her skin colour.

"I do not feel secure," she admits. "I want to see my family and live among them in a place where I can relax."

Nidal Khalil, the woman in charge of Nihal's care, says, "The girl has big ambitions and does not want to be bound by her circumstances. I always try to protect her and show her as much care as I can."

"All I have is a job at a sweets factory in the Abu Rawash area, which pays me EGP 2,500 a month, and a food card from the UNHCR, but that is not enough for the needs of the house, and I was expelled from an apartment before that because I was unable to pay the rent," Khalil continued.

Nidal admits that she cannot be a substitute for Nihal's family, and that the child needs a lot of psychological support to help her adapt to her new life.

Jeremy Hopkins, UNICEF's representative in Egypt, says that unaccompanied children face many problems, including their legal situation and a dearth of assistance programmes.

According to Hopkins, among the challenges facing unaccompanied children is their poor financial situation, their inability to access government services, and their vulnerability to abuse, bullying, and prejudice.

Regarding the services provided by UNICEF to these children, Hopkins says that mental health support is provided to about 2,000 unaccompanied children, out of a total of 4,100 children in Egypt, through cooperation with the Egyptian Red Crescent Society.

Hopkins added that UNICEF monitors the cases of unaccompanied children and passes these cases onto the UNHCR to help reunite them with their families.

Children who are in high-risk situations are provided with the necessary services, or their cases are forwarded to other organisations like the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, according to Hopkins.

Hopkins also noted that the UNHCR supports government agencies like the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood in building a national system for child protection.

He also affirms that financial assistance is provided in emergency situations and that services are provided to all children regardless of gender.

‘In some circumstances, we provide limited financial assistance’

According to Heba Al-Azzazi, the director of the Refugee and Migrant Program at Save the Children, the organisation assists children in registering in schools and educational centres.

Al-Azzazi says that the organisation deals with approximately 1,500 unaccompanied children of various nationalities each year, and that it has a case management team that assists at-risk children by communicating with various authorities.

According to Al-Azzazi, the organisation provides unaccompanied children with limited financial support in some circumstances until they are registered with the bodies tasked with providing financial support.

Al-Azzazi notes that while the organisation does sometimes provide assistance to cover the cost of food or temporary shelter at a safe house, it focuses its efforts primarily on moral support.

"We work with a large number of organisations to provide the necessary support for children. [These organisations include] Caritas, the Catholic Relief Organization, CARE, and Terre d'Azur, and sometimes we deal with local associations to provide food or children's clothing,” Al-Azzazi said.

"We provide psychological and social support and children are trained on how to plan for their future, integrate into society, and overcome the difficulties they face. We also provide individual psychological support sessions for those that need them."

Despite the different experiences faced by these children, the thing that unites them is hardship; from the harsh conditions in their country that forced them to separate from their families, to the dangerous journey with smuggling gangs, and the continued struggle they face at their destination.

* Some names of children used in this story have been changed to protect their identity

** The Arabic version of this article was first published in Zatmasr.com on 13 September 2021

*** To watch the video report click here

Short link: