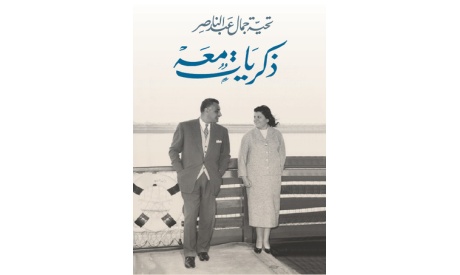

Taheya Abdel-Nasser's memoir, published 30 years after she passed away.

Zikrayat Ma'ahu (Memories with Him) by Tahiya Abdel-Nasser. Cairo: Dar El-Shorouk, 2011. pp.136

Tahiya Abdel-Nasser, wife of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel-Nasser (president from 1954-1970), is a different brand of presidential wife. Not lured by the temptations of power and the glare of media coverage, she shrank from the limelight during and after Nasser's presidency until she passed away in 1990. Moreover, and in stark contrast to Jihan Sadat and Suzanne Mubarak who were considerably westernised (in the official media, both were labelled "Egypt's first lady" along the lines of US presidents' spouses), Tahiya represented the traditional, middle-class wife of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. She devoted her entire life to her husband and children, remained aloof from the public sphere, and did not interfere with her husband's professional life.

Tahiya's memoir was recently published by Dar El-Shorouk. The book sheds light on her relationship with Nasser since their engagement and marriage in 1944 until his death twenty-six years later.

Since her involvement in the political process was minimal, her memoir does not reveal many secrets or juicy details that usually attract the fans of this literary genre, but this does not diminish its importance and relevance. The book provides a direct and personal account of Nasser's personality: his simplicity and stubbornness, his sympathy with the underprivileged, and his suicidal dedication to work, and it affords a glimpse into his idiosyncrasies, such as his penchant for cinema and photography and his aversion to leading a privileged life. The book also, quite exceptionally, reveals some romantic moments in the life of the couple. For example, Tahiya gladly recalls that Nasser carried her up the stairs of their house on the day of their wedding, and that he sent her 46 letters during his 10-month dispatch to Palestine in 1948-49.

Tahiya wrote her memoir in 1973 (three years after Nasser's sudden death) and did not intend to publish it. It was only twenty years after her death in 1990 that the family decided to disclose her personal testimony to the public. Historians explain that memoirs and biographies that are not originally intended for publication are considered more credible than those which are published while their authors are still in office.

The book also zooms in on Nasser's relationship with his five children (Hoda, Mona, Khaled, Abdel-Hamid and Abdel-Hakim) and how he sought to raise them. This was Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s, when fathers still played a dominant, semi-domineering role in the lives of their offspring. But despite the influence of times and Nasser's conservative "saidi" (southern) background, Nasser held many progressive ideas about the upbringing of children and the role of women in society. For example, he did not interfere in any way in his daughters' choices of husband. Also, Tahiya writes that Nasser was totally against beating children as a method of nurturing them. "If a child is beaten, he/she will develop a sense of fear, and will protect himself/herself with lies. And by the time they grow up, they will get used to lying," he told her.

Tahiya narrates some interesting incidents in the book. For example, she writes that Nasser refused to accept a gift of jewellery sent to his office by a wealthy Arab businessman. But his Chief Secretary, Salah El-Shahed, kept nagging, and reminded him that the gift was worth more than 100,000 Egyptian pounds, which prompted Nasser to retort: "I did not revolt for money or jewellery. I can double my salary tomorrow if I wish, but this is not what I did the revolution for." Nasser afterwards told Tahiya: "Salah annoyed me." Nasser's unwillingness to compromise his integrity was normal, but it seems exceptional these days as we learn more and more about Mubarak's henchmen's gross corruption, profiteering and squandering of public funds.

Nasser did not compromise either on his commitment to the service of his country. When the activities of the "Free Officers" group intensified prior to the 1952 coup, Tahiya unburdened her heart to him. She was concerned about her and her children's fate if he got arrested. But Nasser's reaction was harsh. "How selfish. All you care about is your husband and kids? Only your family? This means that you are only thinking of yourself."

The book is divided into 136 pages of text and a 110–page appendix that includes photos of Nasser and his family.

Nael M. Shama, PhD, is a political researcher and writer based in Cairo.

[email protected]

Short link: