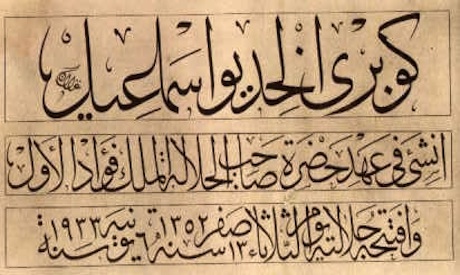

Foundation Stone of Khedive Ismail Bridge 1931-1933 by King Fouad I

If lions could speak, they would tell of the courage, the tears, the honour, the faith and the martyrdom of the Egyptian people. The four bronze lions guarding the two ends of the Qasr el Nil bridge, one of the oldest bridges in Cairo, have witnessed a great deal; from the lovers watching the sunset and eating grilled corn on the cob to the roars of millions of Egyptians who marched on the bridge chanting for freedom, equality and the toppling of Mubarak's regime.

During the 25 January revolution, the lions were the backdrop to a sea of peaceful protesters and their battles against teargas, rubber bullets, live ammunition and the armoured cars that ran over them.

They were also the background to victorious Egyptians who climbed their pedestals to hold the Egyptian flag as high as possible, celebrating the toppling of 30 years of tyranny.

Silent witnesses

Even decades before the revolution, the lions have always been the silent witnesses of major events in Egyptian history.

Fascinated by the statues filling the grand squares in Paris and London, Khedive Ismail commissioned the famous French sculptor Henri Alfred Jacquemart and Charles Henri Joseph Bordier, whose busts of African and Arab men were highly esteemed in France, to create a statue of Mohammed Ali, as well as four bronze lions and a statue of Ibrahim Pasha, writes Lesley Lababidi in her book: Cairo's Street Stories.

Henri Alfred Jacquemart was one of France’s most popular sculptors, who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and received many honours for his exhibitions from 1847-1879. According to Joseph G.Reinis in his book "The Founders and Editors of the Barye Bronzes", Jacquemart sculpted the four lions in bronze as it is considered the best metal for casting and moulding sculptures, filling the finest details of a mould.

His finest works in Egypt also include the Viceroy Mohamed Ali statue in Alexandria ordered in April 1869, the Sulleiman Pasha statue in 1874, and that of Mohamed Lazoglou Bey in 1875, as documented by Pierre Kjellberg in "Bronzes of the 19th century".

Jacquemart's four bronze lions were initially intended to stand guard around Mohammed Ali's statue in Alexandria. Instead they were set to guard both ends of the newly-built Khedive Ismail bridge that linked Ismailyia (Tahrir Square and down town) with Gezira island (Zamalek) back in 1872.

Toll stations

Egyptian Chafika Soliman Hamamsy writes in her book "Zamalek: The Changing Life of a Cairo Elite", that the first role these guards played was in March 1898 when the lions served as toll stations, where farmers and merchants paid a tax to cross over to reach the grand market, where they exchanged and traded goods. Taxes depended on the type of goods and the means of transportation passing through, so that owners of old camels had to pay two Egyptian piastres for example, whereas owners of young camels paid 30 barra (about ¾ of one piastre). Donkey owners paid one piastre and 15 barra.

The bridge used to open at 9 am each morning for ships and boats to cross the Nile and again from 1 pm to 2.30 pm. Rare cinema footage of the lions’ daily activity was documented by cinema founders the Lumiére brothers, Auguste and Louis and is featured in Egyptian director Madkour Thabet’s documentary film entitled Sihr Ma Fat Fe Kenouz el Mare’yat (The Magic of Lost Visual Treasures).

In the heart of Cairo

Located in the heart of Cairo, and one of the gateways to Tahrir Square (Liberation Square) Cairo's most spacious square, the lions witnessed the funerals of iconic Egyptian figures, including former President Gamal Abdel Nasser and beloved singers Um Kalthoum and Abdel Halim Hafez during the 1970s.

In "If Lions Could Speak" Egyptian writer Samir Raafat says that the original size of the bronze lions was much smaller. During the renovation of Gezira bridge from 1931-1933 (at a cost of LE 108,801) King Fouad I ordered the relocation of the bronze statues and because of the enlargement of the Gezira bridge, the lions had to be modified to fit the new bridge. Their height was extended by two metres and they were accordingly remoulded.

In 1933 it was renamed the Khedive Ismail bridge and then changed to the Qasr el Nil bridge (the Palace of the Nile in Arabic) after the military coup in 1952 and was further renovated to accommodate traffic.

The history of Egypt has been rewritten many times but the nation has its favourite guards to chronicle the story of Cairo for generations to come. Though they stand in silence, yet their roar is getting louder each day, giving strength and courage to the Egyptian people as they head towards democracy, freedom, and reform.

Modern Egypt, a tale told by Lions’ roar

Modern Egypt, a tale told by Lions’ roar photo by Ati Metwaly

photo by Ati MetwalyShort link: