March 4 marks the 122nd birthday of the vernacular poetry pillar Beiram Al-Tounsi (1893-1961).

“I joined the (1919) revolution my way, I didn’t throw stones, didn’t break lamp posts, but I wrote verses that were more powerful than rocks and even bombs,” Beiram Al-Tounsi said.

On the occasion of his 122 birthday, Ahram Online revisits the relics of Beiram Al-Tounsi, as described in a PhD on his role in journalism, by Zeinab Abdel Aziz (1979), under the title Media in the ‘relics’ of Beiram Al-Tounsi.

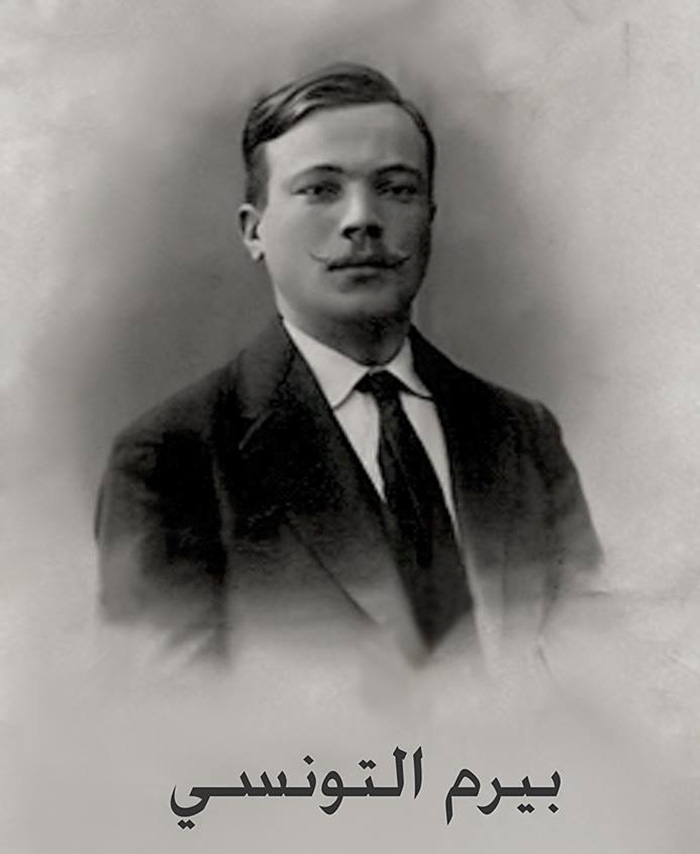

Mahmoud Beiram Al-Tounsi (Photo: Courtesy of poet Omar Fathi)

Born to parents of Tunisian origin, Al-Tounsi was born and raised in Alexandria. After his father passed away when he was 14, and his mother at the age of 17, Al-Tounsi got married. “From the age of 17 to 25 he was busy earning his daily wages to support his wife and two kids,” reads the PhD.

His education was limited to elementary school, yet he was a book worm and read just about anything he could put his hands on. “A big portion of his knowledge was also in the wrapping paper he used to sell goods in, for he read it before hand.”

His self-education journey is what truly shaped his culture and nourished his great talent. Of all the folk heritage, Arabian Nights was his favorite. However, the real turning point in his life was when he first read books of the Sufi pillar Ibn Arabi, and delved into the world of Sufism and the contrast between it and the state of Muslims back then. His cultural criticism of the social and political status of Egypt and the Arab world at that time was always accompanied by a vision for reformation, an alternative other than satire.

Since a big portion of the Egyptian population were uneducated at that time, trying to convey his message via the usual ‘sophisticated’ classic Arabic, be it in poetry or prose, was quite a barrier to Al-Tounsi.

Consequently, he deviated to colloquial poetry and enhanced the beauty and simplicity of Egyptian slang into verses and stanzas. Before Beiram Al-Tounsi, slang poetry was limited to what is known as zagal rhymes that focus on wit and humor. Al-Tounsi was the first to take it up to a whole new level where wit and artistic slang are interwoven.

And so with a zest of daily life rituals against a background of folk epic chants such as Abu Zeid Al-Helaly and Diab, Al-Tounsi created his vernacular poetic legacy. He rhymed the whole world in a witty sharp poem that always sided with the people. His profound understanding of Egyptian socio-political status made even his shortest poem a real social mirror of that era.

By the early 20th century, Al-Tounsi was well known and his poems and articles were often published in various Alexandria local magazines such as Al-Afkar and Al-Ahaly. In 1917, his satiric poem Al-Magles Al-Baladi (City Council) was a national hit. The poem that criticised the tax increase enforced by the city council was written in neat Arabic calligraphy and hung in various stores, translated to several foreign languages and recited by all. The hit poem ended each verse with the word ‘city council’ had verses like:

A baby’s cries for bread will go unnoticed for we are busy collecting money for the city council, Oh thou fig seller, how much money for your children and how much will you keep for the city council?

By the eruption of the Egyptian revolution in 1919, Al-Tounsi sided with the people and wrote poems in support of Saad Zaghloul and all national political figures. By then he was denied permission to publish his first magazine. In reaction to that, he folded a sheet of paper into eight folds, called it the Masalla, lahi garida wala magala, (the obelisk, neither a magazine nor a newspaper) put his photo on the front page and wrote under it: “Mahmoud Beiram Al-Tounsi, poet of the City council poem.” Hence he needed no government permission to print since it’s technically a new genre of publication that is not yet listed by the law.

Al Masala, First independant Egyptian magazine (Photo: Courtesy of poet Omar Fathy, founder of Beiram el Tounsy's facebook page)

The first issue of Al-Masala was published on his birthday, May 4, 1919. It was numbered with alphabets instead of figures, and was sold for 5 mallims just like the rest of the magazines.

Al-Masala was a great success, a thing that encouraged him to move it to Cairo after the fifth edition of which he wrote and edited himself while he focused on resisting colonialism and all of those who feed on it and war.

After criticizing the marriage story of Sultan Fouad in his famous lyric: Marmar Zamani ya Zamani Marmar, Al-Masala was banned from publishing, he then published another one called Al-Khazouq (The impaler) which was also banned and he was exiled to Tunisia in 1920. In Tunisia the authorities kept a close eye on him due to his powerful effect on the general public. He fled to Leon, France and corresponded with Youth of Cairo newspaper. In 1922, he came to Egypt under a false identity.

Al-Shabab, newspaper founded by Al-Tounsi during his exile in Tunisia, (Photo: Courtesy of Esmat El Nemr founder of Misrfone online radio)

By then he worked with renowned music icon Said Darwish and wrote several poems for him and one of the most inspiring operettas titled “Shahrazad” that was first played in 1921. His fame was inevitable and soon the Egyptian authorities returned him to France in 1923.

Courtesy of Misrfone

“In 1938, he was on a boat passing by Port Said and was crying his heart out, when an Egyptian fisherman saw him and asked him to try to sneak into the Egyptian land,” read the PhD. He succeeded and hid in the homes of his best friends among which were renowned writer Abbas Al-Akkad and the sheikh of composers Zakaria Ahmed.

His artistic legacy flourished since then and together with grand singer Omm Kalthoum and Zakaria Ahmed, they created the golden music triangle. He wrote several musicals such as Aziza w Younis and the lyrics of Youm Al-Qeyama (Domes Day).

He was granted Egyptian nationality by the Revolution government in 1954. He was among the editorial team of Al-Gomhoriya newspaper (first daily newspaper to be published by the revolution) and wrote several radio programmes such as Al-Zaher Beibars, and Hekayat Zaman (Old Tales) that is a selection of folk tales and even some riddles. Al-Tounsi died in Egypt in January 5 1961, but his legacy is time resistant.

Today, as a celebration of his birthday, Misrfone online radio shall stream episodes of musical Master piece Aziza w Younis, written by Beiram al-Tounsi and composed by Zakaria Ahmed

Short link: