The intertwined histories of an Antiquities-registered palace and an artistic community with roots that go as far back as 1936 are the source of heated debate fuelled by conflicts over rent control, ownership rights, artistic and architectural legacy.

An open gate beckons to an old palace, rooms full of fresh paintings stacked against the wall, intricate frescos laced over in dead vines, and rich wood panelling filmed in dust.

L’Atellier Alexandrie. (Photo: Fatemah Farag)

“I was here painting in 2015 when thugs with vicious dogs attacked us,” recounts Ahmed Senbel. We are sitting in his corner of what was originally built to be a garage but since the 1950s it has been a place for artist residencies. “I remember thinking – as one of the thugs did damage to a Tanbouli painting – that these people had no care for the art. That we were in the midst of a battle over property and money but what is at stake is so much more.”

We look around at his paints and canvases. The questions loom heavy: Are they safe for now? Will he be forced to remove them soon? And where will they all go?

The plight of L’Atellier Alexandrie has come to the fore of the concerns of many in the intellectual and artistic community in Egypt; an alarm that has been picked up recently by the local media.

According to a statement released by the atellier on 9 February, “The owners [of the property] obtained a court decision on 27 January 2021 for our removal. The ruling is based on the Supreme Administrative Court decision in 2019 to invalidate Article 18 of Law 136/1981.”

The latter was a law that protected the rental contracts of legal entities. “The decision of the Supreme Administrative Court in 2019 does not just affect the atellier but all civil society organisations, education institutions and others who had rental contracts,” explained the atellier’s legal counsel Ahmed El-Ghirban. “For example, the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria is also being evicted.”

The atellier is petitioning the 27 January verdict in court and in the meantime campaigning for survival. “The legal petition will be presented in some 20 days and then with court recess I would estimate another 10 months before a court ruling,” explained El-Ghirban.

In the meantime, representatives of the board are meeting with officials looking for solutions. Earlier this month they met with the Governor of Alexandria General Mohamed El-Sherif who confirmed the need for a “legal solution that would protect the atellier due to its heritage, cultural and educational importance… without negatively impacting the rights of the owners.” (Baladna El-Yom, 15 February 2021) and Minister of Culture Ines Abdel-Dayem who – according to the atellier’s Facebook page – “expressed her complete support and presented several solutions being discussed with the board.”

Esteemed writers such as novelist Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid have come out in support of protecting the atellier and a Facebook group has been the bulletin board for impassioned pleas using the Arabic hashtag “SaveAtellierAlexandrie”.

L’Atellier Alexandrie

(Photo:Fatemah Farag)

Artistic evolutions

In 1934 renowned Egyptian artist Mohamed Nagi – a pioneer of modern Egyptian painting who studied under Claude Monet and would also establish El-Marsam in Luxor [now a hotel] and the Cairo Atellier – was invited to exhibit his work at the L’Atellier Athena.

“He went with his friend writer and historian Gaston Zananiri and they were both so impressed with the experience that they decided to establish an atellier in Alexandria upon their return,” explains Esmat Dawastashy, an Alexandrian artist and the only person to attempt a comprehensive documentation of the atellier published under the title: The History of L’Atellier Alexandrie 1934-2004.

The relevance of the date is not just that it shows that the atellier has been around for a long time. The inception of L’Atellier Alexandrie came at a time when the Egyptian art scene was filled with activity.

The School of Fine Arts in Cairo, established in 1908, had graduated some of the most esteemed Egyptian artists of the time, including Ragheb Ayad, Mahmoud Said, and Mahmoud Mokhtar.

The war saw the presence of foreigners such as writer Lawrence Durrell (who fled the Nazis in Greece), the Jewish Hungarian photographer Etienne Sved, and British painter Robert Medley in Egypt, and the exchanges that took place were impactful to that generation of Egyptian artists.

A Surrealist movement was on the rise led by artists such as Antoine Malliarakais (Mayo), poet George Hennein and photographer Lee Miller who came to Cairo when she married businessman Aziz Eloui Bey. (Art et Liberte: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt 1938-1948).

And in 1946 luminary artists, such as Hamed Nada, Samir Rafi, and Abdel-Hadi El-Gazar, would form the Contemporary Art Group (Dreamers and Rebels, Rawi Magazine, Issue 8).

L’Atellier Alexandrie

(Photo:Fatemah Farag)

Alexandria was also the scene of the establishment of art schools such as the “Italian Don Bosco School for the Education of Art Crafts, the Amateur Fine Arts Society established by Hassan Kamal which held the first Art Salon in Alexandria in 1931 in a palace on Sharie Fouad,” says El-Dawastashy, commenting on the relevance of Alexandria as the home of the atellier at that time.

In his book he adds details such as “The British Council set up an amateur art section for British soldiers who could be seen in the Shalalat Gardens and on the Cornice painting the beautiful city. And a group of French and Egyptian intellectuals set up the Egyptian French Friendship Society.”

The initial board of the atellier reflected the diversity of the time and included Zananiri, composer and musician Enrico Terni, and the orientalist painter Giuseppe Sebasti.

L’Atellier Alexandrie

(Photo:Fatemah Farag)

“The foreigners at the time had great influence and teaching within the Egyptian art scene,” explains artist Reem Hassan who has been a member of the atellier since she entered the University of Fine Arts in Alexandria in 1990 as a student, including having taken on positions on the board until 2019.

A professor at Alexandria University’s Faculty of Fine Arts Painting Department, she explains that “One of the achievements of the atellier was that it created a space for the connection between foreign and Egyptian artists – not just painters but musicians, poets and writers. And the Egyptian masters who had come into contact with the foreigners went on to impact the next generation – the atellier represents a continuum of rich history and learning.”

The boards that followed also reflected the centrality of the atellier to the public and intellectual life of the city drawing to its leadership over the years Ahmed Abdel-Hady, the famous Alexandrian lawyer, renowned Egyptian artist Seif Wanly, Dr Mohamed Lotfi Doweidar, surgeon and head of Alexandria University, Engineer Radamees El-Laqani, head of production at the Kafr El-Dawar Factories, artist Neama El-Shishini,a professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Dr Shams El-Din Abul-Azm, head of the Faculty of Pharmacy, and since 2000 Dr Mohamed Rafik Khalil, a professor of surgery at Alexandria University. (El-Dawastashy)

In 1939 and on the occasion of a visit by Dr Taha Hussein, one of Egypt’s literary giants who would become the minister of education in 1950, to speak at the atellier, Al-Ahram newspaper wrote: “The group is made up of the most prominent photographers/painters, sculptures’ and foreigners working together to create a permanent artistic movement … and it organises individual exhibits for artists in Egypt and from abroad."

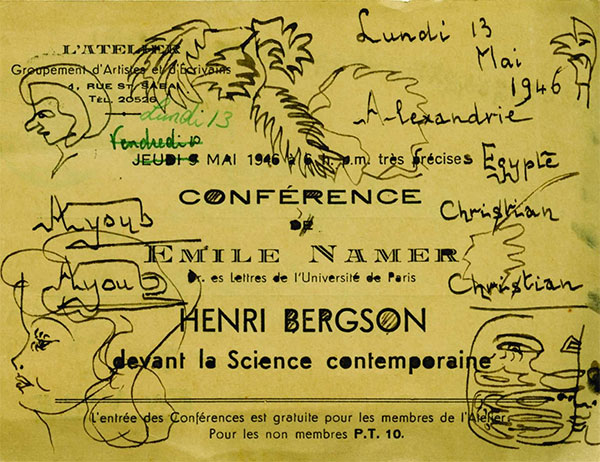

Photo credit: Centre D'Etudie Alexandria CEAlex.

"The latest was for a Japanese photographer last April. And this group is credited with making it possible for Alexandrians to see the miracles of French sculpture by organising an exhibit of French sculpturesthat included Rodin and others… and in recognition of this continuous effort it receives an annual stipend from the Ministry of Maaref [Knowledge] and another from the Alexandria local government.”

The picture that accompanied the article included Taha Hussein, his wife, and Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil, and behind them paintings by Mahmoud Said on the premises of the atellier. (re-print by El-Dawastashy).

And since those early days the atellier has gone on to be credited as a centrefor artistic activity and the hot house that brought to the fore the acclaimed 1970s and 1990s generations of Alexandrian artists.

Photo credit: Centre D'Etudie Alexandria CEAlex.

Mohamed Abla takes time to reminisce: “I remember well my first solo exhibit which took place at the atellier in 1975. It was inaugurated by Seif Wanly and that was such an important moment for me.” To that generation of artists it was not just about the paining. “The atellier formed the collective memory of generations. It was there I learned music. Listened to poetry.I would see the governor of Alexandria always around because it was such an important place to be. I mean you really could not go to Alexandria and not stop by.”

A 1978 brochure published by the organisation expanded on the intellectual mandate of the space: “Within the context of the atellier’s mission and throughout its history it has been a place where the theater productions of the most prominent foreign and Egyptian writers have taken place. It has been a place for cinema, music, and wonderful social events to receive, introduce, and say good-bye; where influential personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals can meet… the atellier is a melting pot of all forms of knowledge and culture; literature and art for all parts of society.” (Atellier Alexandrie and Its Mission, Alexandria, 1979)

Another high point in the trajectory of the organisation was in the 1990s.

“I joined in 1990 and had my first exhibit at the atellier in 1994 and am part of the generation that included luminaries such as Wael Shawki and Ahmed Nawar and Mostafa El-Razaz,” remembers Hassan. “We would work day and night. There were talents and new trends to be discovered. We interacted with the Youth Salon established by Farouk Hosny (artist and former minister of culture). The atellier was a place of opportunity: to travel abroad through joint programmes to Germany and Italy, to participate in the Biennale. To be a part of it all,” she added.

Everyone will acquis that what they describe is probably not so evident today. “They [the atellier] are a group that is closed onto themselves,” says Israa El-Naggar, art trainer at Shelter Art Space and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina and founder of Cairo Mockingbird.

We are sitting at the offices of Shelter Art Space, self-identified as “developed by SIGMA Properties-Egypt, as an artplatform to promote the artistic scene in Alexandria” run under the dynamic leadership of Chaymaa Ramzy.

Ramzy sits back and echoes the sentiment: “I remember going years ago to sign up for a drawing class. It was so dark.” And it seems the classes were not too good either.

“The point is not that it was – and is – not important,” clarifies Ramzy, “But to say that maybe the problem is deeper rooted than the dispute over location.”

Senbel explains, “there have been ups and downs over the course of the history of the atellier.” The upturns follow the downturns. They always have.

6 Victor Basili Street

In 1956 Mohamed Nagi moved the atellier to its current residence in El-Azarita district.

The stamp “Fondera Martinelli Allessandrie 1893” on the wrought iron outer fence has led many to document the date of the building as being 1893. However, the Department of Antiques has said that foundries often stamped the date of their own establishment and that the date of construction was 1925 in the era of King Fouad I.

Everyone agrees that the palace was bought by the Alexandrian wood merchant Edward Karam who then commissioned all of the wonderful wood panelling and floors that remain to today.

Karam sold to the Banco di Roma who – having been impacted by the 1956 nationalisation laws– had an empty palace on their hands which they then rented to Nagi in the same year. The bank eventually sold the property to someone else who then – according to Centre d’etude Alexandrines (CEAlex) – reclaimed the garden and built the apartment buildings that mar the street today.

Up past the marble balustrade is a salon of sorts where board member Hani El-Sayed Ahmed and I sit sipping tea with cloves. Ahmed has a more nuanced recollection of the late 1960s, early 1970s. “When the owners took procession of the garden it was part of an arrangement for us to keep the rental contract which was at the time EGP 35.”

We step outside of the palace and look beyond the charming strip of vegetation being tended by a gardener. A wall of concrete the length of the property looms above us.

“Not only have we managed to keep the building in good condition all of these years with our meagre resources, we went the extra mile to ensure it was recognised by the antiquities and heritage departments. We did that. Not the owners,” affirms Ahmed.

The underlying argument is if it had not been for their organisation and their meagre rental the buildings that remain might have met the same fate as the gardens.

“The owner in 1974 was Abdel-Fattah Samak and when he passed away his son went to court in 2011 to file for the eviction of the atellier and this case languished in the courts until the 2019 decision of the Supreme Administrative Court voiding rental contracts between legal entities that were renting for non-housing purposes,” recounts lawyer El-Ghirban.

Ahmed acknowledges “It might be very difficult to tear the building down now because this is a red zone [protected area] and because so much is being said about the property and because we got it registered. But we see it happen all the time.”

Stories of old buildings going down because the water is left on, or a mysterious fire breaking out, or a building simply being left to become derelict and fall to pieces are commonplace across the country. “All around us architectural heritage is compromised. And while the rent we pay may not be much, the amount we spend to keep up the building and the effort we have put into protecting its integrity is considerable,” says Ahmed.

And make no mistake the stakes are high. According to some board members, an external evaluation of the value of the property was conducted some five years ago and the estimated value was EGP 100 million. While no one gave me an exact figure it is clear, moving up from the EGP 35 mark in the 1970s, that the rental paid is a small sum to which an estimated EGP 10,000 are added per month for upkeep.

When I share these figures with Alexandrian architect May El-Tabakh she does not bat an eye. “Yes, that would seem like a reasonable estimate. And the rental value [to a bank or business] would probably be around EGP 70,000. If you were in the position of the owner how would you feel?” she asks. Indeed.

And when I share the EGP 70,000 rental estimate with some of the artists back at the atellier they are all incredulous. “A month?” comes the weary response. “We might be able to raise the money once, twice, but really how can a non-profit group of artists come up with that kind of money?” wonders Alyaa El-Gereidy, an Alexandrian artist and counted as one of the famous 1990s generation.

The 2015 incident was decided in favour of the atellier at the time with the governor of Alexandria, head of security and others intervening and ending the on-site clash which had artists occupying the premises to defend it against thugs. “At the time, I was not renting space at the atellier but as soon as I heard the news I ran there and stayed until everyone was safe. It [the premises] is our home, our history,” recounted El-Gereidy.

But Mohamed Metwalli, head of the Alexandria Antiquities Department, said in a television interview to ONTV earlier this month that the building and what remains of the garden are registered as antiquities – number 598 – and stressed that the laws regulating antiquities are capable of preventing the destruction or violation of the building and its environment in any form.

He clarified “Let it [the building] go back to its owners. This is an affair that does not concern the Antiquities. The building is not just registered as an antiquity,but it is also protected under Law 144/2006 as a heritage building and registered in the Heritage Register for Alexandria. And the law is strict – no one can even paint a wall inside without a written permission from the Antiquities.”

Projecting forward: Where the building, the atellier’s legacy and the nature of the city intersect

“It is not just the atellier. So many civil society organisations that were at the heart of Alexandria are shutting down because they can’t keep up with market property rates. They are evicting the Faculty of Fine Arts from its location and building an alternative on the highway. And at the same time, a place like Saraya El-Haqania in the centre of town is left to be overrun by rats,” says Hassan.

As El-Gereidy and I mull over the options, she asks: “Isn’t the presence of the atellier on 6 Basili in the heart of Alexandria – behind the Graeco-Roman Museum, and around the corner from the Goethe Institute, Shelter Art Space, and others… is that not also a value that cannot be replaced by any other kind of rental?”

There is a strong inclination to look to the state for a solution. “Similar buildings [and legacies] do not face the same conflict [abroad] for a very simple reason,” wrote Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid, “And that is because the state buys the premises from its owners and leaves it alone especially if it is an arts and culture symbol, and in this way the state gives the owners their rights and gives arts and culture their rights.”

Artist Mohab Abdel-Ghaffar sits amongst his canvases on the top floor of the atellier– early work from the 1970s jostling for space against the in-progress painting and everything in-between. “Just look at the Emirates – giving citizenship to professionals and artists. It shows the appreciation of the state for art as a headline of a developed civilisation,” he remarks.

Abdel-Ghaffar indicates that perhaps in spite of the importance the state puts on promoting enlightenment and confronting terrorism and extremism, the appreciation of the role of artists and spaces such as the atellier is lacking even though they are critical components of achieving those goals. “For all of these reasons the state should step in,” argues Abdel-Ghaffar.

As far as legal council is concerned, energies should go into a campaign for legal change that would impact not just the fate of the atellier but all those legacy civil society organisations and educational institutions that are being impacted by the legal change.

“In 2020, a draft law was mobilised by the government – and it was also passed by the House of Representatives’ Housing Committee – to address the negative social and economic impact of immediate eviction and offered legal entities a five-year grace period to find solutions. This draft was shelved by the speaker of parliament in the same year and until recess,” he added. As far as El-Ghirban is concerned, this draft should be found and activated.

But should the life of the atellier be extended within its current space– or even at a different location – can it continue on the same strategic trajectory? Atellier resources, comprised of the EGP 100 annual fees paid by some 200 people in addition to small sums of money for residency fees, make it an impossible challenge to find an alternative space should they need to.

“Where can we go? An apartment. A room for an exhibit hall and some desks. How does that match the legacy or support the work,” wonders Senbel. While Hassan points out “Artists need space. They need context. They need the green. You can’t just push them into a box and say it is the same. These palaces and houses that we have inhabited have not been perfect but have offered us that essential environment that generation after generation have connected to.”

In the case of the atellier, as in the case of many of our historical landmarks being challenged by competing interests and changing cities, there should be a bottom line. One that is summed up by Abla as follows: “We should all care about the atellier because it is not just a building or an organisation. It is a historical landmark and when we ask for it to remain we are in fact asking for a better future for culture. And for Egypt.”

Short link: