In the last decade, Egypt has had two revolutions, three presidents, two constitutions and a handful of parliaments

When, after 30 years in power, former president Hosni Mubarak was forced from office on 11 February 2011 nobody foresaw the political upheavals that lay ahead.

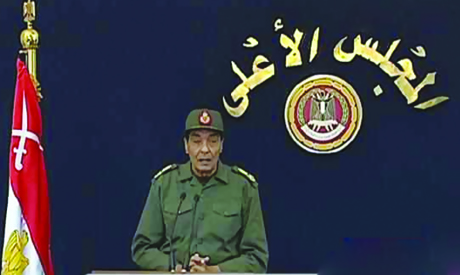

Days after Mubarak relinquished power the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) issued a six-article constitutional declaration, vowing that a civilian government would be elected within six months but meanwhile disbanding the People’s Assembly and Shura Council. A month later SCAF issued another constitutional declaration that included 63 articles regulating future presidential elections and paving the way for a new People’s Assembly and Shura Council. And before SCAF handed executive power to the new president following presidential elections in June 2012 it issued a third constitutional declaration granting itself the right to veto any future constitutional changes, and to hold onto legislative powers. The declaration was denounced by many political forces and figures. Former UN diplomat Mohamed ElBaradei described the step as “a setback for the state and the 2011 anti-Mubarak revolution”.

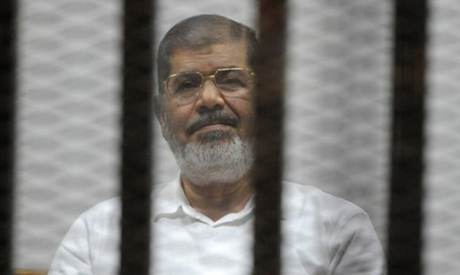

When the Muslim Brotherhood came to power in June 2012 it soon became clear that president Mohamed Morsi had a similar predilection for constitutional declarations. On 22 November 2012 he issued a seven-article constitutional declaration that allowed him to fire the prosecutor-general and appoint a replacement, protected the Islamist-dominated Shura Council from dissolution, and placed presidential decrees beyond any kind of appeal.

The declaration was met with a wave of protests. Popular anger grew after an Islamist constitution was promulgated on 25 December 2012. The 236-article constitution was widely seen as laying the foundations of a religious state.

Six months later, following a massive popular uprising on 3 July 2013, Morsi was removed from power and placed under house arrest. A 50-member constituent assembly was formed to draft a new constitution which was passed on 18 January 2014. It banned religious parties, and restricted the office of president to two four-year terms. The latter stipulation was overturned when amendments to the 2014 constitution were passed on 17 April 2019. Among the changes was an extension of the presidential term from four to six years, meaning that presidential elections will fall in 2024 rather than 2022, and allowing the incumbent, President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi, to stand for another six-year presidential term, meaning he could remain in office until 2030.

When Mubarak left office in February 2011, minister of defence and head of SCAF Hussein Tantawi was automatically declared president of Egypt. Tantawi remained in place until he was replaced by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Morsi who, after being declared the winner of the 2012 presidential election, took office on 30 June 2012. Instead of unifying the nation, Morsi’s one year in office brought violence and instability, exacerbating the stand-off between Islamist forces, including the Muslim Brotherhood and ultraconservative Salafis, and civilian forces.

Morsi was replaced by Adli Mansour, the chairman of the Supreme Constitutional Court, who became interim president on 3 July 2013.

Though faced with serious security and economic difficulties, under Mansour Egypt began gradually to restore stability. Security forces worked unremittingly to contain the post-Morsi unrest, and a pathway was opened to new presidential elections.

On 8 June 2014 Al-Sisi was sworn into office. The immediate challenges he faced included battling an explosion in the number of terrorist groups and steering Egypt back on to sound economic tracks.

Al-Sisi’s success in cracking down on terrorist organisations such as Hasm (Decisiveness), Gond Masr (the Soldiers of Egypt), and Ansar Beit Al-Maqdis in North Sinai, garnered international praise, says security expert Khaled Okasha. Egypt’s membership of the African Union was restored, and between 2016 and 2017 it secured a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

Political unrest and the upsurge in violence had, however, wreaked enormous economic damage, and the already decimated tourist industry ground to a halt following the downing of a Russian plane in Sinai in October 2015. Egypt turned to the International Monetary Fund for help, entering into a deal which Al-Sisi described as “a bitter medicine we must swallow to escape our economic crises”. Inflation skyrocketed.

Abdel-Hadi Al-Qasabi, leader of the Support Egypt parliamentary majority, told Al-Ahram Weekly that it was President Al-Sisi’s security and economic successes that persuaded MPs to give him a chance to run for another six-year term beyond 2024.

Samir Ghattas, an independent political analyst, agreed. He told the Weekly the political parties and MPs responsible for drafting the 2019 constitutional amendments clearly viewed Al-Sisi as a symbol of stability and economic success.

The past decade witnessed seven constitutional documents and five presidents, a reflection of the turbulent times through which Egypt has passed. One reason for the massive protests in January 2011 that drove Mubarak from office, says Ghattas, was widespread anger at the blatant rigging of the 2010 parliamentary elections, which explains “why people welcomed SCAF’s first constitutional declaration dissolving the Mubarak-era People’s Assembly and Shura Council”.

SCAF, however, faced an uphill battle in preparing for post-Mubarak parliamentary elections as severe differences emerged between Islamist and civil forces over the laws which should regulate the poll. The first post-Mubarak parliament, which held its inaugural meeting in January 2013, was destined to become the shortest-lived House in Egypt’s parliamentary history. In June the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) ruled that the People’s Assembly should be dissolved because it had been elected under laws that unfairly discriminated against independent candidates. Islamist forces viewed the dissolution as part of a conspiracy concocted by SCAF and in response the Muslim Brotherhood attempted to turn the Islamist-dominated advisory Shura Council into a full-fledged legislative house.

The Shura Council was itself dissolved following Morsi’s ousting in June 2013. It then took a year and half for a new parliament — the House of Representatives — to be elected.

The House proved resilient in the face of the political upheavals that hit the country, including the assassination of soldiers and policemen and attacks targeting security headquarters and churches.

Under constitutional amendments passed in April 2019, which stipulated a new second house, the advisory, 300-seat Senate, Egypt returned to a bicameral system. Ghattas now hopes that the Senate, which was elected in September, and the House of Representatives, elected this month, will finally activate Egypt’s political life and move the country towards democracy and the peaceful rotation of power.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 24 December, 2020 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

Short link: