The current Covid-19 crisis has further highlighted the urgency of tackling the twin challenges of climate change and rising inequality that have become the defining challenges of the 21st century. Many scientists have warned that climate change and global warming will lead to a notable increase in the spread of new viruses and diseases and that in the coming years humanity is likely to experience a multitude of new epidemics and pandemics such as the one we are experiencing now.

Moreover, the Covid-19 crisis has put issues of inequality into sharper focus given the uneven effects of the virus on the rich versus the poor, with poorer citizens and minorities experiencing significantly higher fatality rates in many of the countries afflicted by the virus, while also bearing the brunt of the dire economic consequences of the pandemic. The Covid-19 crisis has also highlighted the hazards of globalisation, with many fearing that global supply chains will be interrupted leading to crippling shortages in essential goods in many countries of the world.

Liberal and neoliberal economic policies with their emphasis on unlimited economic growth, globalisation, privatisation and free markets, budgetary austerity and declining spending on social goods and services are seen as largely responsible for the creation and perpetuation of global warming and economic inequality in both the developed and the developing worlds.

Even before the current crisis, many economists had reached the conclusion that neoliberal economics was no longer adequate for taking the challenges of the 21st century and that new economic models needed to be developed to address these challenges. In recent years, a number of such models and paradigms have been proposed. None has yet to be fully embraced by policy-makers as an alternative to neoliberal economic theories, but a few countries such as the Netherlands, Finland and New Zealand have begun experimenting with some of these ideas, paving the way for their potential application on a broader level.

Global urban population

One example is the degrowth economic model that questions the basic assumption at the heart of the prevailing liberal and neoliberal economic models, which is that economic growth is the measure of the health of an economy and that without economic growth there can be no development or prosperity.

According to degrowth economists, unlimited growth will simply lead to the depletion of the earth’s resources and ultimately to the environmental ruin of our planet. They challenge the propositions of sustainable development theories that maintain that technological innovation and efficiency can lead to a decoupling of economic growth from environmental degradation, paving the way for unlimited economic growth, and argue that a more radical paradigm shift is needed.

According to degrowth economist Ricardo Mastini, “degrowth means primarily the abolition of economic growth as a social objective. This implies a new direction for society, one in which societies will use fewer natural resources and will organise and live differently from today. Ecological economists define degrowth as an equitable downscaling of production and consumption that will reduce societies’ throughput of energy and raw materials. In a degrowth economy people would abandon many of the habits associated with present day economies.”

He adds that degrowth economic models generally focus on three broad goals. “The first goal is to reduce the environmental impact of human activities through the following proposals: reduce material and energy consumption; encourage or create incentives for local production and consumption; and promote changes in consumption patterns. The second goal is to redistribute wealth both within and between countries through the following proposals: promote community currencies and alternative credit institutions; promote a fair distribution of resources through redistributive policies of income; promote work-sharing and create a citizen’s income. The third goal is to foster the transition from a materialistic to a convivial and participatory society by promoting downshifted lifestyles and by exploring the value of unpaid activity.”

Thus, in a degrowth society, economies would be localised, consumerism and fossil-fuel consumption minimised, wealth redistribution and work-sharing schemes promoted and methods of direct democracy embraced.

Another variation of the degrowth model that has gained popularity in recent years is the “doughnut model” proposed by Kate Raworth of Oxford University in the UK. This model questions the twin assumptions embraced by neoliberal economics, namely that economic growth is good and that trickle-down economics works. Raworth maintains that the problems of the 21st century are global in scale and require a global commitment to the twin goals of environmental sustainability and social justice. These can only be achieved if we abandon models that take unlimited growth and consumption for granted and that assume that growth automatically leads to prosperity for all.

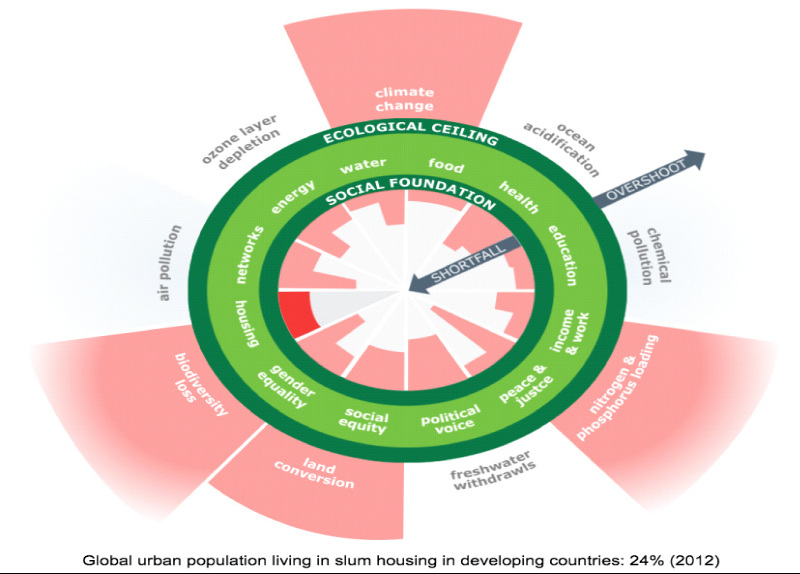

Raworth’s model is summarised in the figure illustrating this article. Inside the green doughnut in the figure are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations and outside the green doughnut are the environmental limits to growth beyond which economic growth becomes unsustainable and threatening to our planet. According to Raworth, all countries should aim to maintain the limits of their economic growth within the green zone or within the green doughnut.

She writes that “the hole at the doughnut’s centre reveals the proportion of people worldwide falling short on life’s essentials, such as food, water, healthcare and political freedom of expression – and a big part of humanity’s challenge is to get everyone out of that hole. At the same time, however, we cannot afford to be overshooting the doughnut’s outer crust if we are to safeguard Earth’s life-giving systems, such as a stable climate, healthy oceans and a protective ozone layer, on which all our wellbeing fundamentally depends.”

These goals can only be achieved if policy-makers adopt deliberate policies of income and wealth redistribution and environmental protection, she says.

Another more partial proposal that has had great popularity in recent years is the universal basic income (UBI) model. Universal basic income proposals suggest that all citizens irrespective of their circumstances should be given a government allowance that would cover their basic needs. This could be achieved by increasing taxation on the wealthy and by replacing many costly and ineffective targeted welfare programmes with a universal basic income. Some countries such as Finland, Canada and New Zealand have already begun experimenting with this proposal and have recorded favourable results.

While these models take the question of climate change and income inequality seriously, their application on a broader scale is likely to run up against many challenges. For one, developing countries that have yet to fulfil many of their SDGs cannot be expected to adopt degrowth models and accept the status quo. Some would even say that degrowth models are a luxury that only advanced countries can afford and that without growth poorer countries will simply remain poor.

The second challenge has to do with politics. Degrowth models suggest a radical redistribution of wealth and resources within and across countries. But in most countries, policy-makers and interest groups reject proposals for the radical redistribution of the income and wealth needed to realise economic well-being for all and aggressively resist such proposals.

Finally, it is not enough to tackle climate change and income inequality on the national level since these have become global problems, with climate change affecting all countries of the world irrespective of the culprits behind it and income inequality in one nation spilling into other nations in the form of refugees and increased immigration. Moreover, the current global financial institutions, which could steer countries in a more sustainable and equitable economic direction, remain the foremost proponents of neoliberal economics and are unlikely to embrace alternative agendas in the foreseeable future.

However, without a radical paradigm shift away from the existing economic models that are leading to the steady destruction of our planet and to growing inequality within and across countries, the future of humanity looks bleak. The current Covid-19 crisis has highlighted that our way of life is simply unsustainable and has placed greater urgency on the need to develop alternative economic models.

Degrowth and doughnut economics provide a compelling critique of neoliberal economics and offer an alternative vision. They may in future provide an alternative roadmap for humanity as a whole.

The writer is a senior researcher at the Al-Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 11 June, 2020 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

Short link: