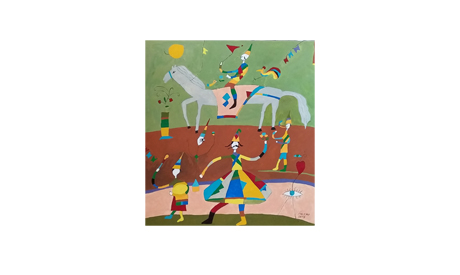

Folk art has existed in Egypt since ancient times, though few contemporary artists pay attention to it. Artist Salah Bisar, best known for his paintings of circus shows and saints’ anniversaries, is the exception. In his latest exhibition at Ubuntu Gallery, “Glee”, he showed 20 small gouache paintings depicting Egyptian folk art.

Born in 1952 in Shanawan, a village in Menoufiya governorate in the Nile Delta, Bisar came to Cairo to study at the art college in Zamalek.

“I felt like a stranger in the huge and horrible capital. I did not dare talk to anyone for a long time. That is why I chose to live in popular neighbourhoods, like Sayeda Zeinab, and Al-Muizz Street, which were larger versions of the village in terms of social relations.

“Depicting life in a typical Egyptian village was something other artists did too, notably the novelist Abdel-Hakim Qassim in The Seven Days of Man. My memories of my village come back in black and white, taking on colour only when they concern a saint’s anniversary or a Sufi ritual.

“I remember the different processions of each group of artisans during the prophet’s anniversary, in which carpenters, fishermen and bakers each had a pageant. It was delightful to see as a child, and since they improvised, often humorously, it was also a learning experience.

“I also remember an influential experience when I was a primary school student: how we stood in line to welcome the procession of the late president Gamal Abdel-Nasser and Che Guevara on their way to visit one of the national manufacturing companies in Menoufiya.”

The son of a government employee who owned a small plot of land, Bisar developed a passion for peasants and their way of life. “I used to join them for the harvest of cotton and other crops. It was very enjoyable.”

Like all village children living in the late 1950s, he would invent his own toys using old cans, matchboxes, thread, and so on. This might have influenced his paintings later on; he developed a peculiar style emphasising cheerful, vivid colours and simple, improvised lines.

After graduating in 1975, Bisar continued to live in different parts of Cairo, such as a small apartment on Nubar Street downtown, where he used to observe the Salaheddin Citadel and some popular celebrations from his seventh floor balcony.

“Actually, at the time, popular festivities were an exciting source of inspiration to visual artists and poets. Take The Grand Night by Salah Jahin, for example. After all these years, I am still keen on attending popular festivities, especially saints’ anniversaries that attract people from different governorates. There are still some traditions that bring pleasure to my heart, such as people who set up swings, moving from town to town to entertain children.

“Creativity is a mysterious moment beyond consciousness. I have seen so many colour compositions. However, I was keen on portraying the scenes of this collection using vivid, unmixed colours, which is the main feature of folk art.

“Conflict in the Arab region has gone to the extreme. It is saddening to see all these negative and horrible events. I believe that art is one of the spaces where humanity can find salvation.”

For Bisar, working as a critic has been a double-edged sword; it enriched his understanding of art history and its different schools and new trends, but at times it slowed his development as an artist.

But art criticism, he says, has deteriorated compared to the way it was in the golden age of art movement in the 1960s, when critics played an enlightening and leading role. “There is a dramatic crisis in the visual arts scene today, and we need to figure out how to solve it.”

However, Bisar, just like his mentor Hussein Bikar, one of the prominent painters in the 20th century and the founder of the Sindbad children’s magazine, has also designed book covers. He has produced over 150 books for children in different age categories, and some of these won awards — at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1997, and the Bologna Book Fair in 2000.

“Children enjoy drawings that stimulate their imagination, and curiosity, and I enjoy doing that,” he says modestly.

This was Bisar’s seventh solo exhibition, and it took him almost a year to finish the collection. The artist has been on many experimental tracks in his career, and he sees his 33cmx33cm paintings as a result of these journeys.

“I am a child inside. A child who is himself suffering from conflicting feelings. I always try to nurture this child.”

Bisar’s paintings adhere to the format of the popular arts school; each is filled with different elements, movement is essential, perspective and proportion are for the most part ignored. Bisar also benefited from the rich legacy of Egyptian proverbs, and popular stories.

The artist chose gouache, which can be thinned with water, for its opaque matte finish, and its primal intensity. This is appropriate in a cheerful collection celebrating living creatures. Salah made many sketches for each painting. The small, expressive paintings have the same elements: the clown, the swing, horses, playful kids raising flags, cats, among others. Although the elements are repeated one way or another, the viewer does not feel bored because the composition and the colour rhythm is different each time. Some paintings have a geometric design, with an invisible triangle cleverly and beautifully made to represent different elements every time it occurs.

“Horses of different breeds and colours were an essential element of popular festivities back in my village; they were trained to dance to a beat. It was a regular scene. As children, we used to deal with different creatures: cats, dogs, chicken, horses, butterflies, roosters, even bees. This exhibition is a call for humanity to find nature and peace.”

*A version of this article appears in print in the 5 December, 2019 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

Short link: