Alexandria was established as the capital of Egypt after Alexander the Great’s conquest of the country in the fourth century BC. Later, in the era of Ptolemy II, the city became Egypt’s main gateway to the outside world and was famous for its ports, harbours, lighthouse — one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World — and above all for its trade.

Today, Alexandria, like any other city by the sea, is famous for its fishing and boat-making, with the latter being something of a vocation that can never become outdated. Indeed, the relationship between Alexandria and Alexandrians and the sea is as old as time.

The famous Alexandria Lighthouse was built specifically for the purposes of sea-born trade, and, guided by Isis Pharia, the ancient Egyptian goddess protecting sailors and fishermen, it was a visible sign of the sea to all Alexandria’s people.

Near Alexandria there have long been fishermen’s villages whose inhabitants live from fishing as a main source of food and trade. But the sea is not always calm, and it can be both a blessing and a curse.

Due to its position as the gateway to Egypt, Alexandria has also suffered from raids and wars throughout its long history. The French Expedition to Egypt in 1798 unleashed political and social events that influenced the structure of the modern city.

Under Egypt’s modern founder Mohamed Ali (1805-1848), Alexandria grew into a city of European influence, and it was the financial and cultural capital of Egypt. The prospect of wealth resulting from trade and construction added to the cotton boom that took place in Egypt in the mid-19th century, and revolutions and ethnic and religious strife in Europe and the Mediterranean later in the century drove many foreigners to seek the security and prosperity the city offered.

It was a safe haven and a burgeoning centre of commerce, and its foreign community continued to flourish. “Seeking to use Egypt as a base from which to expand his power, Mohamed Ali reopened Alexandria’s access to the Nile by building the 72km Mahmoudiya Canal, as well as an arsenal to locally produce the warships intended to rebuild his fleet,” author Abdel-Rahman Al-Rafei says in his book The Era of Mohamed Ali. He adds that in World War I, Alexandria was the chief allied naval base in the eastern Mediterranean.

“The city’s self-governing municipality, founded in 1890, undertook several notable projects, among them the creation of the Graeco-Roman Museum, the construction of a public library, improvements in the street and sewage systems, and the reclamation of land from the sea, upon which the waterfront Corniche was later laid out,” he adds.

“The municipal franchise was, however, extremely restricted: the city council was controlled by a coterie of European and Levantine merchants and property owners, despite the fact that the great majority of Alexandria’s inhabitants were Egyptian.”

Today, if you ask any Alexandrian where he is from, he may very well say min Bahari, meaning from Bahari, the district of many of Alexandria’s most important families. Passing by Ramleh Station in downtown Alexandria with its magical Italian-style hotels to the Hakaneya Palace and the mixed courts, little fishing boats bobbing on the sea will start to loom on the horizon, allowing any visitor to know he has reached the heart of the city.

“The Morsi Abul-Abbas and Bahari districts of Alexandria were originally a cemetery area named Bab Al-Bahr, the “door of the sea” as it faced the sea. These parts of Alexandria were actually outside of the main city where cemeteries were usually built, but as the years went by and more foreigners came to Alexandria, people started developing the city outside its walls,” explains Islam Assem, a professor of history at the Higher Institute of Tourism at Abu Qir in Alexandria.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the walls of the city had mostly been demolished. Bahari and Anfoushi were the first areas to be developed, being close to the city’s main port, and it made sense for these areas to become centres for fishermen. The neighbourhoods were inhabited by people working at the port either in trade or in import and export.

fishermen’s wooden houses along Al-Fanar Street

photos: Hazem Al-Attar

Anfoushi is said to be named after Al-Kahanfoushi, a Muslim sheikh who came to Alexandria by sea and lived in the neighbourhood.

Many shrines (maqam) are to be found in the area to this day. Locals and fishermen still tell stories about these shrines, even chanting songs with the names of the sheikhs as a way of receiving their blessings before going out to sea.

At one point, some of the major families in Bahari built houses still existing there today, and these originally belonged to Moroccan and Tunisian families who had fled to Alexandria after the fall of Andalusia (Muslim Spain), becoming major traders during Mohamed Ali’s era. “Many Alexandrians residing in Bahari have a Moroccan or Tunisian origin,” says Wael Azab, the grandson of one of Bahari’s leading fishermen who proudly recalls his memories of growing up there during the 1970s.

Azab said his great grandfather had been Moroccan, like many residents of Bahari. He had come to Alexandria and married an Alexandrian woman “whose family were also fishermen,” and accordingly he became a fisherman following the profession of his in-laws.

“Most of the big names in the fishing business have similar stories, names like Al-Dallal and Al-Tartoushy who mostly worked in trade, though some were also religious sheikhs,” Azab added. Alexandria’s Ibrahim Pasha Mosque is named after a sheikh from Morocco.

The residents of Bahari were often of Andalusian, Jewish, Levantine or Turkish descent. The Andalusian and Turkish influence was quite distinctive, and the Bahari fishermen’s traditional dress of wide-legged trousers, or sayala, was influenced by Turkish traditions. Moreover, the Alexandrian cuisine is quite similar to that of Andalusia.

“There are fish and seafood tagines such as al-sayadia and al-kamoniya. There are lots of garlic, vinegar, and celery. To this day, an Alexandrian fish dish cannot be cooked without those three main ingredients, all of which are Moroccan-inspired,” Azab explains. There is also the famous Moroccan sweet couscous dessert, which is eaten best in Bahari’s renowned pastry shops such as Azza and Al-Sheikh Wafik. “I remember my grandmother cooking couscous in the traditional Moroccan way,” Azab adds.

Al-Hagary, Al-Sayala, Ras Al-Tin, and That Al-Soor are the names of famous streets in Bahari, all of which were once home to fishermen families. There are houses with massive doors, high ceilings, and wooden balconies. Every street once had its own fettewa, or tough guy, and the residents had a competitive attitude towards each other. “Someone would say I am from Al-Sayala, while another would reply with an air of confidence that I am from Al-Hagary,” Azab said.

photo: Hazem Al-Attar

During the khedive Abbas Helmi’s era at the end of the 19th century, a popular wrestling competition used to be held annually between the fettewas of each street and the winner would receive gold from the khedive. Azab recalls the story of Hamido Al-Faris who won the annual competition but refused to pick up the gold from the floor, so the khedive ordered another wrestling match with one of his strongest slaves as a punishment. Luckily, Hamido defeated him with one headbutt and was then given the title of “knight” or Al-Faris.

Azab is the administrator of one of the biggest Facebook groups dealing with Alexandria’s history, called “Stories of Alexandria”.

“I wanted to tell people historical facts about Alexandria in a storytelling way, and to give information in the form of a story. It is a way of documenting the traditional customs of Alexandria that will soon be gone,” he explains.

Bahari became known for small fishing boats, big ships, and yachts alike. There were people selling and binding fishing nets. “My grandmother used to make different kinds of fishing nets using needle and thread. In those days, the nets were made of cotton,” Azab recalls. Now made of nylon, the nets are still one of Bahari’s traditional crafts.

A fisherman would also go out to sea without really knowing where he was going. If he owned a small boat, he would go out some four or five km from the shore. The bigger the boat, the deeper he went out to sea. “There were no compasses, and some big boats would stay out at sea for days,” Azab said. “Because the sea is full of wonders, when you are standing far from it, all you see is water, but when you are at sea, it is a different story,” he added.

Each part of the sea has its own kind of fish. “There was no GPS back then, but the fishermen knew the sea like the backs of their hands. They knew what kind of fish they wanted and where and when to find it. Today, we will go west for sardines; tomorrow we will sail east. The longer they were at sea, the more experience they gained.”

New nets were made by the women of Bahari at home. “My grandmother used to make fishing nets at home, each for a certain kind of fish, depending on its size. They were usually made of cotton or linen. When the net got ruined, it was fixed by men waiting for a new expedition,” Azab said.

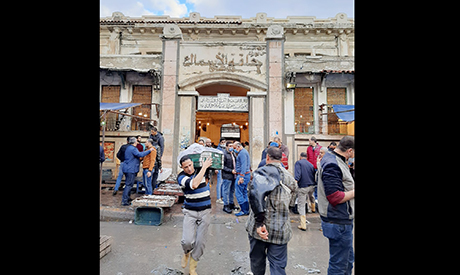

The fish market (Halaket Al-Samak)

photo: Mohamed El-Sayed

Said to be derived from al-mekoos, or tariff, this area of Alexandria was the place where tariffs used to be paid on goods coming in by sea.

There is a saying that the “sea loves wood”, and there are still houses made of wood in the Al-Max district today only a 25-minute drive from Ramleh Station. The fishermen work from sunrise to sunset, and it is impossible to find fish fresher than those available in this district of the city. There are colourful three-storey wooden houses known as fishermen’s houses along Al-Fanar (lighthouse) Street. Everything seems to be straight out of a village painting, with fishermen untangling their nets and tasty dishes standing ready full of colour and spices.

Despite their threatened heritage, these two districts will always stand out as the origin of Alexandria, adding to the smell of the sea that cannot be felt anywhere else as much as in this city. Mohamed Ali chose to build a palace at Ras Al-Tin, still standing today, and another was built at Al-Max during Said Pasha’s rule, though this unfortunately was later demolished.

Some years ago, efforts were made by local NGOs and the governorate of Alexandria to include fishing as part of the city’s intangible heritage, making it eligible for UNESCO protection. “Due to various setbacks and difficulties communicating with the fishermen and their sheikhs, the project was not completed,” Azab said, but there are still hopes that this protection can be found in the future.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 28 January, 2021 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

Short link: