Alexandria has abundant ancient heritage and picturesque architecture. It was founded to be a beacon of diversity, enlightenment, and artistic endeavour. This cosmopolitan city is the home of various cultures, the traces of which are still very much alive today.

Dating back at least two millennia, particularly to the city’s founding by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, Hellenism in Alexandria still exists today. In 2018, the government introduced the Nostos Initiative that has been welcoming Greeks who used to live in Egypt to visit their old neighbourhoods in Alexandria.

In ancient times, the Hellenistic city was famous across the then known world and included one of the Wonders of the Ancient World in the shape of the famous Alexandria Lighthouse, the Pharos. Other important institutions in the city were the Library, the Mouseion (the Temple to the Muses), and the Necropolis (the Catacombs of Kom Al-Shoqafa).

Alexandria’s charm today dwells not only in its streets, buildings, neighbourhoods, squares, cafeterias, restaurants, and other spaces, but also in its diversity, which evokes immense nostalgia among residents and diasporic visitors. As a melting pot of various cultures, the city has been home to many foreigners, especially people from Greece, Italy, Armenia, Romania, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, and Russia.

They lived and worked in a multicultural society that embraced all races and religions and celebrated each other’s various occasions and holidays. Such diversity created a highly tolerant atmosphere. Some chose to marry from the same community, while others married from other ones.

In recounting her childhood memories of cosmopolitan Alexandria, Greek patisserie owner Evangelia Pastroudis shared her story with readers. Originally from Lemnos, a Greek island, her family lived happily among Egyptian, Armenian, and Italian neighbours. It was a close-knit community that functioned as one big family in good times and bad.

“We were seven sisters, and our Egyptian neighbours took care of us when there were demonstrations during and after World War II. They would take us to sleep in their house, which was on the safer side of the street,” Pastroudis remembers in her contribution to Voices from Cosmopolitan Alexandria published by the Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

But events after the war, including the nationalisations of the 1960s, led large numbers of such nationals to emigrate to other countries. Some chose to stay where they felt they belonged more than anywhere else, however. Others came back to Alexandria after their retirement to discover that many of their businesses, religious venues, and cultural and educational institutions were no longer there.

GREEK COMMUNITIES: The presence of the Greeks (Egyptiotes) in Egypt dates back to 323 BCE and the start of the Hellenistic era following the death of Alexander the Great.

“Many Greeks and citizens of other Hellenistic kingdoms immigrated to Egypt and settled there after Alexander the Great invaded Egypt in 332 BCE to make it part of his Macedonian Empire. After his death and the division of his Empire among his leaders, Egypt became a kingdom under the rule of the Ptolemaic kings, a date that marks the beginning of the Hellenistic era,” explained Doaa Bahieddin, a senior researcher at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria.

“But relations between Egypt and Greece go back much further than that. Archaeological evidence from Crete and Mycenae of Egyptian antiquities dating back to the first half of the second millennium BCE bears witness to the existence of strong relations between Egypt and Crete during the era of the Pharaonic 18th Dynasty (1550-1350 BCE).”

“In the Al-Sawi period of the 26th and 27th dynasties (664-404 BCE), Egyptian-Greek relations were strengthened again when the Egyptian king Psamtik II, with the help of Greek mercenaries, put an end to Assyrian rule in Egypt. The relatively dense Greek presence in Egypt during the 26th Dynasty, followed by their presence as rulers after the conquest of Alexander the Great and the rule of the Ptolemies, produced a cultural blend between the Egyptian and Greek civilisations,” she said.

“The cultural blend between the Greeks and the Egyptians is palpable throughout history. One of the many pieces of evidence for this is Aegyptiaca, a history of ancient Egypt in Greek authored at the beginnings of the Ptolemaic period by the historian Manetho Al-Samanudi, one of the most important priests at the shrine of Heliopolis.”

“Moreover, ancient Greek intellectuals always valued Egyptian civilisation. The ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Eudoxus, for example, lived for 13 years with the priests of Heliopolis, trying to benefit from their knowledge. The ancient Greek historian, geographer, and writer Herodotus, also known as the ‘Father of History’, visited Egypt in 450 BCE. Thanks to him, we have a detailed account of the mummification process, the events that were held to honour gods, and other local customs. According to his writings, the Greeks were among the first foreigners to visit ancient Egypt.”

The cultural movement in Egypt sparked the interest of the Ptolemaic kings to establish scientific institutions intended as resources for all the citizens of the ancient world, the most important of which were the museum and ancient Library of Alexandria. Demetrius of Phalerum, the ruler of Athens in the late 4th century BCE who later became an advisor to kings Ptolemy I and II, inspired king Ptolemy I Soter to build a Library to house the world’s most important books in various fields.

The city of Alexandria, a capital of culture and art in the Mediterranean, then went on to witness the first translation of the Old Testament of the Bible into Greek, done under the supervision of Demetrius and Ptolemy II. Many Egyptians also learned Greek, which was then the official language of the government and the Ptolemies.

At the end of the Ptolemaic period, the fusion of Egyptian and Greek civilisations had reached a climax, when queen Cleopatra VII, keen to learn the Egyptian language and showing a clear bias towards the Egyptian national religion, portrayed herself as the goddess Isis. Inspired by her Egyptian heritage, Cleopatra died by suicide, possibly by means of an asp, a poisonous Egyptian serpent and symbol of royalty, which is also the most important component of the crown of Lower Egypt.

Much later in the 18th and 19th centuries of the modern period and particularly after the Greek War of Independence from the former Ottoman Empire in the 1820s, many Greek people settled in Alexandria, with others living in Cairo, Port Said, Aswan and Assiut. By the 1950s, there were some 400,000 such Greek citizens living in Egypt, with at least 200,000 in Alexandria.

Cavafy

Moreover, Egypt has been the home to noteworthy Greek artists such as Jani Christou, Jean Desses, Maria Giatra Lemou, Nelly Mazloum, and Nikos Tsiforos, along with painters like Konstantinos Parthenis, writers like Penelope Deltam, and poets like Constantine Cavafy. There were also politicians, diplomats, and other figures.

In 1843, the first Greek community association was established in Alexandria not only to serve Greek interests, but also to contribute to Egypt’s social, professional and philanthropic development. The members of this community established literary publications along with a variety of clubs and institutions providing artistic activities. The area where the Patriarchal Monastery of St Savvas the Sanctified and the Greek Hospital, guest house, and school are located today was a main attraction for the community in Alexandria.

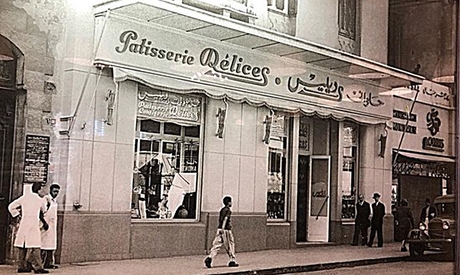

Among the most prominent Greek districts in Alexandria is Ibrahimia, known as “Little Paris” where multiple Greek and Italian stores were located. “We would go to Enosis, to the sailing club and to Delices, which was, and still is, a restaurant and a patisserie, and it is Greek,” commented Eleni Konidi, a Greek-Egyptian teacher. Egyptians and Greeks lived in harmony, and they mingled to form one close-knit society, sharing the same core manners and values.

Another Greek community was founded in Cairo in 1856 centred in the three main neighbourhoods of Hamzaoui, Haret Al-Roum, and Tzouonia. In Hamzaoui, a patriarchate was established at the St Nicholas Greek Orthodox Cathedral. There is also a monastery that still exists in Old Cairo in the shape of the Monastery of St George where a Greek school, hospital, and home for the poor and elderly were located. Other Greek communities were founded in Minya (in 1812), Zagazig (1850), Mansoura (1860), Port Said (1870), and Tanta (1880).

A 1903 photo of the Alexandrian tram

GREEK PROFESSIONS: The Greeks excelled in business, and some prominent families, such as the Averoffs, the Benakis, and the Gianclises, became well-off as a result of running businesses in Egypt.

But prestige did not matter to many Greeks who also worked as chefs, merchants, barbers, florists, and in many other jobs. They passed on their skills and experience to Egyptians.

The Greeks established the Anglo-Egyptian Bank and the General Bank of Alexandria. They took part in the development of the cotton and tobacco industries. Some of the famous families involved were the Benakis, the Salvagos, and the Rodochanakis. They also worked in the theatre, cinema, and newspapers and cooperated with Egyptians to advance these areas. They were known for their businesses in cheese, butter, toffee, and biscuits.

Wealthy Greek bankers, merchants and industrialists donated large sums of money to various causes in Egypt and Greece. Their money mostly targeted the construction of hospitals, schools, and universities. Some of the best-known donors were Michail and Eleni Tositsas, George Averoff, Emmanouil Benakis, Nikolaos Stournaras, Nestoras Tsanaklis, Konstantinos Horemis, Theodoros Kotsikas, and Vassilis Sivitanidis.

One of the richest Greek families that lived in Alexandria for 150 years or more was the Zervudachis. Even though Emmanuel Zervudachi left Alexandria at the age of 17, he still visits it every year. The poet Bernard de Zogheb dedicated his poem “Waiting for Zervudachi” to Emmanuel’s family, and it is similar to the famous poem “Waiting for the Barbarians” by Cavafy.

“During World War II, my father was a major in the British army. He had Greek nationality, but he did not speak Greek well. My mother was also Greek, but they spoke English and French with each other, not Greek. I think it was my great grandfather who built the family mausoleum in the Greek Orthodox Cemetery,” comments Emmanuel Zervudachi in his contribution to Voices from Cosmopolitan Alexandria.

The community left many examples of Greek architecture behind in Alexandria, where many hospitals, apartment buildings, churches, schools, orphanages and clubs were constructed by the Greeks. The Greek Club by the Qaitbay Fortress in Alexandria is a major example of Greek architecture and culture. After its opening in 1909, the Club was a meeting point for Greeks in the city and then became a social and cultural hub for all residents and visitors to Alexandria regardless of nationality. It represents a blend of the Egyptian and Greek civilisations, shown off in the food, setting, and atmosphere.

“There are only around 5,000 Greeks in Alexandria now,” said one Greek resident. “But generally speaking, the community remains one of the most integrated and influential in Egyptian society. The Greeks have been the most similar to the Egyptians throughout history, and the Greek Club reflects the Greeks’ influence in Alexandria.”

A 1950 photo of Patisserie Dèlices

EXODUS: The post-1952 regime led by former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel-Nasser affected the Greek community as well as other foreigners in Egypt. It marked the rise of Arab nationalism and the peak of the exodus of the Greeks from Egypt.

Many of them had their businesses and properties nationalised. Losing their source of income made the majority of them leave the country and travel either to their homeland or to other countries.

Today, there are some 5,000 Greek individuals left in Egypt, including those who have obtained Egyptian nationality. “We, who are left behind, love the city because Alexandria gave us so much. She made us who we are. We feel at home, let’s say,” says board member of the Greek community of Alexandria, Paris Macris.

The Greek imprint is still crystal clear in Alexandria, a city rich in heritage, history and culture. There are numerous stores, neoclassical buildings, and neighbourhoods with Greek labels and architecture, and the EKA (the Greek Community of Alexandria) has a gymnasium, a nursing home, a cemetery and schools.

In addition, after being shut down for about years, a Greek Patriarchal Theology School has been reopened. Many Greek buildings in Egypt have been renovated by the Greek government and the Alexander S. Onassis Foundation, including Cairo’s Church of St Nicholas, Old Cairo’s Church of St George, and a number of buildings in Alexandria.

Over the past decade, there has been an increasing interest by the Egyptian government in strengthening diplomatic relations with Greece through focusing on the Greek diaspora. In addition, an expansion on the economic level has taken place between Egypt and Greece, manifest in the generous amounts of Greek investment in Egypt in the fields of tourism, banking, and oil, to name only a few.

The NCSR Demokritos Institute in Agia Paraskevi, Athens, and the University of Alexandria have signed a five-year cooperation agreement that addresses archaeological research and other matters.

Since his inauguration in 2014, President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi has boosted relations between Egypt, Greece, and Cyprus, and the leaders of the three countries have met at some five tripartite summits. Hosted by Fotis Fotiou, the Cypriot presidential commissioner for humanitarian and overseas affairs, a cooperation protocol was signed at the presidential palace in Nicosia in Cyprus in 2017 to initiate a diaspora programme with Egypt, and the Egyptian government has exerted significant efforts to make the programme and associated Nostos Initiative successful.

The initiative aims to encourage Greeks and Cypriots, as well as their descendants in Alexandria, to reconnect with each other and with their second home in Egypt. Giving this programme the green light is regarded as a milestone in the political, economic, and cultural relations among the three countries.

The Greek word nostos means “return to roots”, encapsulating most of the goals of the Initiative. It also symbolises the idea of the return of the ancient Greek heroes to their home, as found for example in the Odyssey. According to the daily Al-Ahram, the world nostos was thus an obvious choice by the ministers from Egypt, Greece, and Cyprus in preparing the programme.

Al-Sisi, Cyprus President Nicos Anastasiades, and Greece President Prokopis Pavlopoulos inaugurated the Hellenism Roots Revival Week held in Alexandria, Cairo, and Sharm El-Sheikh between 30 April and 6 May in 2018. The event aimed to recall the Greek diaspora’s memories in Egypt and to revive the shared heritage and culture between the three countries.

In an attempt to strengthen relations between Egypt, Greece and Cyprus, the week was inaugurated by the Egyptian authorities to pave the way for Greek and Cypriot diasporas to visit the country that used to be their home. Numerous cooperation treaties were signed by the three countries during the week in Alexandria with the aim of stimulating economic, industrial, and commercial collaboration among them.

Egypt’s Minister of State for Emigration Nabila Makram reiterated the significance of the initiative for those who used to live in Egypt. “There has been strong interest from Greeks and Cypriots who wish to participate in the project,” she said, while adding that of course everybody is equally welcome to visit Egypt.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 24 June, 2021 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

Short link: