“The Arabs were anything but barbarians — their great city of Cairo is a sufficient answer to that charge. But their civilisation was oriental and of the land, and it was out of touch with the Mediterranean civilisation that evolved in Alexandria,” says Alaa Khaled, a novelist born and living in Alexandria.

“At first, the Arabs made efforts to adapt the city to their needs. The Church of St Theonas became part of the huge Mosque of the Thousand Columns, for example, and the Church of St Athanasius also became a mosque. [However], towards the end of Arab rule Alexandria did indeed regain some importance: the Mameluke sultan Qait Bey built the fine fortress that bears his name on the ruins of the classical Lighthouse as a defence against the growing naval power of the Ottoman Turks.”

Ramleh trams in the 1920s; a postcard of the St Mark Church (photos from the book Alexandria City of Memory)

“The Ottomans conquered Egypt in 1517, and a new but equally unimportant chapter in the history of Alexandria begins. This is what the English writer E M Forster said about Alexandria in his Alexandria: A History and A Guide. Forster reflected a lot on the transformations Alexandria had seen, and I guess his book is one of the deepest that have been written on the transformations of the city,” Khaled adds.

Arriving in Alexandria’s Al-Manshiya Square, he looks at the granite unknown soldier memorial in the square and comments that “there used to be a statue of the khedive Ismail here, but it was removed to the Graeco-Roman Museum after the July Revolution in 1952.”

As he notes, the square was once associated with the name of Egypt’s early 19th-century ruler Mohamed Ali, who is associated with the “heyday” of Alexandria and its once-celebrated cosmopolitanism. “Mohamed Ali opened the door for many foreigners who wished to come to Egypt. Predictably they came first to Alexandria and many, especially the Greeks, stayed here,” Khaled says.

“This square was at the very centre of the city with the Mixed Courts, the Cotton Exchange and the Bourse surrounding it. This part in the middle of the square was called the French Gardens.”

It was in 1840, under the direct supervision of Ibrahim Pasha, that Italian architect Francesco Mancini designed the rectangular Square that was first known as the Place des Consuls. Many Italians, including architects and artists, were coming to Egypt in search of better lives. “They were encouraged to come, but they also liked to come,” Khaled says.

A postcard of the St Mark Church (Photos from the book Alexandria City of Memory)

He adds that Italian architects have left many imprints all over the city, but Mancini’s Square is particularly significant as it was part of the modernisation of a city that was expanding with the arrival of more and more newcomers at the time.

The Majestic Hotel, now neither a hotel nor majestic, overlooks the former French Gardens. It was there that Forster spent his early months in Alexandria in the early 20th century.

“It is just offices nowadays. This is not an elegant part of the city anymore, not the kind of place for a posh hotel. The square passed its prime long ago,” Khaled explains. “But it is still a very significant part of the city.”

Just as the name of Mohamed Ali is firmly associated with the square so is that of Mancini. According to many Alexandrians, the name the square carries today of Al-Manshiya is probably a derivative of the name of its 19th-century designer.

“Such derivatives are an integral part of the story of Alexandria. Things change, but they often keep a strong trace of the original. In fact, they almost always do,” Khaled says.

Abdel-Nasser’s speech in Manshiya Square

However, Al-Manshiya Square also has its own history as it saw one of the high points of the nationalist revolt led by Ahmed Orabi against the khedive Tewfik in the late 19th century.

The demonstrations that started on 11 June 1882 ended with the British invasion of the country on 11 July. This evolved into an occupation that only ended with the 25 July Revolution in 1952, when king Farouk, the country’s last ruler from the Mohamed Ali family, had to leave the country aboard his yacht from Alexandria.

It was an occupation that attempted to re-impose its will on the country in 1956 with the Tripartite Aggression that came in the wake of former president Gamal Abdel-Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal, which was announced on 26 July 1956 from no other square than Al-Manshiya.

“1882 was a very significant year for Alexandria. This part of the city was largely destroyed under the bombardment of the British navy, and much beautiful architecture was lost. But one building that remained relatively intact is the building that hosts the Al-Hendy Café,” Khaled adds as he moves with the fresh early morning breeze behind him.

A Place For Regulars

“The anfrato, literally meaning a cleft, has always been there for residents of the city who wished to gather ahead of social protests.

This was a spot where young people would gather during the 18 days of the 25 January Revolution, for example, and it was to the Al-Hendy Café that many of us who joined the protests would go,” Khaled says.

clockwisefrom top left: Mohamed Ali statue in Manshiya

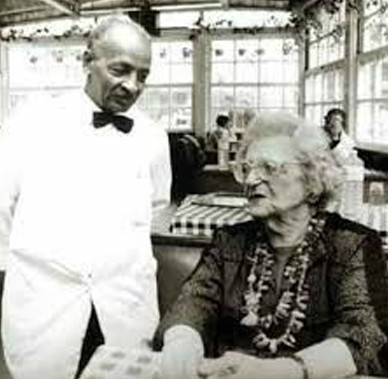

Regulars make up the vast majority of clients, and according to waiter Mohamed they receive a warm welcome. They are regular in the sense that they either come on daily basis or on particular days for particular hours of the day.

Mohamed has been a waiter at Al-Hendy’s for over five years. He had not, as Khaled would say, seen the days when the café was the hub for leftists in the city in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Nor did he see the 1977 food riots when protesters found a refuge in the café.

“The café is a secluded place, which is why so many people who might feel lonely come here rather than go to one of the other cafés in the city with a corniche view. Many of the regulars may suffer from hearing and speaking difficulties, so they come here where they can still feel close to the happening part of the city but without having to be so much in it.”

“They engage without having to be exposed. This place is so fitting for the name of anfrato. The name no longer stands, but the spirit of the name still fits,” Khaled says as contemplates his next destination.

Manshiya Square in the 1920s (Photos from the book Alexandria City of Memory)

He walks northwards, heading towards St Mark’s Church that was built by the English architect James William Wildt in the middle of the 19th century on land granted to the English community by Mohamed Ali.

According to Forster’s History and Guide, the “English were granted land to the north of the square… the French and the Greek to the south; areas were also acquired by communities [like] the Armenians.”

Mohamed Ali, Forster wrote, had wanted to energise Alexandria early on. This was why he constructed a 45-mile canal called the Almahmoudieh “after Mahmoud, the reigning sultan of Turkey”.

Mohamed Ali gave Alexandria a new vibe, but the city was not the centre of power in Egypt as it had been centuries earlier, Khaled notes.

“Mohamed Ali also gave the city the basis for its sleek cosmopolitanism that at times still seems to overlook the wider history of the city. That cosmopolitanism was true and was beautiful, but it was not what Alexandria was all about because there were other parts of the city where the vast majority of Alexandrians lived. I grew up in Al-Hay Al-Araby (the Arab Quarter) where the houses had Ottoman or Mameluke style windows, some of which are still there today,” Khaled says.

Christina, owner of Elite Café

He adds that the two parts were connected by the tram that used to come closer to Al-Manshiya “but does not do so anymore”.

On his way out of St Mark’s Church, now almost taken over by followers of the Coptic Orthodox faith with the declining number of Anglicans in the city, Khaled moves towards the Rue des Soeurs.

“In Arabic we call it the Sharie Al-Sabaa Banat (Seven Girls Street), but it has the same association with the seven nuns who once lived on this street and who according to one story were supportive of the entry of the Arab conquerors to the city in the seventh century CE.”

“They had seen the suffering of Christians under Byzantine rule, it is said. According to another story, they lived in the early 20th century and used to take it upon themselves to keep the street well lighted in the evenings to help passers-by, especially women, avoid hazards,” Khaled says.

Cavafy’s house

In the accounts of vendors on the street, which has always been a commercial thoroughfare, the nuns were Greek.

“They might and might not have been — nobody knows the true story, but it makes sense that people would say they were Greek because of all the Europeans who lived in Alexandria in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the Greeks were the most integrated and most liked by the people of the city,” Khaled says as he walks towards the heart of cosmopolitan Alexandria at Ramleh Station.

In this part of the city there are many imprints of the Greeks who lived and still live in the city. Khaled stops by the house of prominent early 20th-century Greek-Alexandrian poet Constantine Cavafy that now serves as a Greek cultural centre.

The street where the building stands carries the name of the poet. It was Rue Lepsius when Cavafy lived in it.

“Cavafy used to walk on an almost daily basis from this house to the relatively nearby Elite café where he would be welcomed by Madame Christina, the remarkable owner,” Khaled says. Christina, a charming white-haired lady, would never lose control of the details of the menu of her small restaurant nor that of the company of her cats. The Elite has lost its charm since she passed away even though it is still in the ownership of her family.

“This is not the case with the Délices café, where the owner is still keeping the property of her parents in very good shape at the heart of Ramleh Station,” Khaled says, as he walks in its direction. On the way he stops on Adib Street where Sameh Ali, who is walking to the Cap d’Or bar, immediately greets him. “Come and have a coffee with me at Al-Sheikh Ali,” Sameh offers.

Sameh is the nephew of Ali, the man who used to be the supervisor of the bar in its heyday when it was still owned by French and Greek nationals.

“When it was time for the French and the Greek owners to leave Egypt, they decided to pass on the ownership of the place to my uncle. He would never miss his Friday prayers, so he would close the business to go to pray. He did not like the idea of alcohol being served during Friday prayers,” Ali said.

Alexandrian Attitudes

This attitude back in the 1950s provided a good anecdote to fondly joke about. “And so it was Sheikh Ali who took over from the original Cap d’Or,” Ali says.

Today, the bar still keeps its interiors and for the most part the menu is for food, with the fried calamari being as crunchy and fresh as ever. “Stella beer has not lost its ground. It is not just about the price. Egyptians like beer — they did before other drinks became more affordable and they still do today even though we have reduced the amount we purchase of some items.”

“This place has seen great days and nights. It used to be the destination of the top brass of king Farouk and then Nasser’s regime. It used to be frequented by top movie stars like Omar Sharif, Roshdi Abaza and Ahmed Ramzi. I wish we had kept pictures. Those were the days,” Ali says.

Khaled walks towards Ramleh Station by Sherif Street and looks at some of the old buildings whose beautiful architecture is now overshadowed by clusters of street vendors.

“We could not have imagined that there would come a day when street vendors would be on this street,” says Matilda, an elderly half-Greek, half-Slovenian woman who still lives in the same apartment on Rue Sherif Pasha where she got married back in the early 1930s.

“This was a place for high-scale bars and bistros that used to be frequented by top-notch cotton traders. It was the financial hub of the city. Those were different times,” she adds.

However, Matilda is not unhappy about the street vendors. “You cannot stop things. You cannot freeze time. This is how things are. We get old, and we look different, or we just decide to look different.There is not any big wealth running around this part of the city anymore, even if the banks are still there,” she says.

“The street vendors are kind and pleasant. They see me and they say, ‘Madame, do you need anything.’ This is why I would never leave Alexandria. The people are warm. They care for one another. They always have been and they still are,” she says.

“Some things change, and some stay the same. This is the story of every city, and it is certainly the story of Alexandria,” Khaled says as he steps into Délices. He likes to sit in the middle area, which still keeps up the old-fashioned interior almost as it was when this tearoom was opened in the early decades of the 20th century. He likes to order a coffee that the old waiter does not call a Turkish coffee.

To the right and left, the other two salons have been fully redecorated to look like the interiors of chain cafés. “A pity,” commented an older lady visiting from Cairo.

“Well, we have to update so that we can continue to appeal to the younger generation. We have kept one part in memory of the good old days,” says Alica, the third-generation owner of Délices.

Alica has also gone the extra mile to update her menu, now dotted with red velvet and cheesecake assemblies. “We have to appeal to our clients. Not everyone is interested in the retro style; however, we have kept most of our signature items, especially the desserts. But things change,” she adds.

Stepping out of Délices, Khaled explains his unease at the limitations of the debate over the transformations that Alexandria has been witnessing.

Most of it is about the decline of cosmopolitanism, “and not enough is about the transformation of the intellectual debate that followed the 25 January Revolution, which really re-energised intellectual and political debate in the country.

There has also been the receding influence of Salafism, which saw much more popularity then than it has today,” he says.

Khaled agrees that it is perfectly legitimate to worry about the loss of the city’s architectural heritage, however. “This is really taking a toll on the city,” he says as he walks towards Fouad Street, the longest street in Alexandria supposedly laid out by Alexander the Great.

It was on this street that British novelist Laurence Durrell worked “at the British Information Office. The building is still there lost among many others,” Khaled says.

“Look at Rue Fouad. I barely recognise the street now, with all the knocking down of one building after another,” laments Roxane, manager of Chez Gaby, one of the oldest pizzeria restaurants just off Fouad Street.

“They say this building or that building was not registered as a monument. But so what? If they have high aesthetic qualities they should be kept as a memory of the city,” she adds.

Chez Gaby, originally established by a Greek and an Italian before it was sold in the late 1950s, had a Lebanese owner who passed away and left his spouse Roxane to run the show.

Is she still holding on to the restaurant’s memories? “We stick to the old recipes and the old-fashioned ways of doing things. This is the legacy of the place, and we would like to keep it, at least for as long as I live. I am not so sure about the future,” Roxane says.

Khaled comments that many of the third and fourth generations of the foreign families that used to live in Egypt have opted out.

“They came for economic purposes, and because they found it easy to live in Alexandria back in the 19th century they left in the second half of the 20th century when the attraction for them was no longer there. This includes not just the Europeans but also the Shawam [Syrians and Lebanese] who are often forgotten when the history of the city over the past two centuries is being told,” he says.

Few people today would recognise the association between some leading Syrian-Lebanese families and the villas overlooking Fouad Street, he says. Not many will remember that the St Saba Church is associated with the presence of the Shawam in Alexandria in the 19th century.

Bazil Behna, whose grandfather came to Alexandria in the 19th century from Aleppo in Syria, has managed to regain part of his film-production company that was sequestrated in the 1960s.

He is convinced that when the history of the Shawam of Egypt is written, they will be mostly remembered for their cultural influence ranging from cinema and literature to cuisine.

“But it is a history that requires a lot of research, given the ups and downs and the diversity of the lives of the Shawam, at least in this harbour city,” he says.

“Despite all its transformations, Alexandria is still a city that opens up to newcomers. This is one of the cities that has so easily and lovingly welcomed the new waves of Syrians who have fled the bloodshed in their country. I guess it is in Alexandria more than any other city that they have so easily integrated,” Khaled says.

“This has been the case with the Greeks, with the Shawams, and with the Jews: they all settled easily here, and they all had very successful businesses and very eventful social lives. But of course change ultimately occurs and political and economic transformations.”

“I think that whatever the transformations the city has seen, it has always been a city where people could come and melt into. They would be part of the city, but they would still be themselves with their own cultures, identities, churches and synagogues. They might live in their own quarters, but they would still be part of the city,” he concludes.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 12 July 2018 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: Alexandria — city of transformations

Short link: