On 1 October this year, curator and architectural historian Mohamed ElShahed will be launching one of the many exhibitions he has been involved with in putting together the architectural history of Cairo.

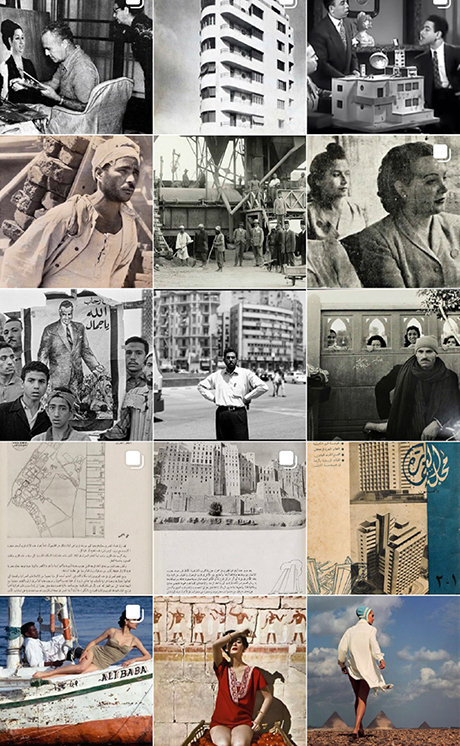

This time, the exhibition is taking place in New York, and it will showcase pictures that document the often-overlooked modern architecture that Cairo saw in the 20th century.

The exhibition relates to a topic that ElShahed has dedicated much work to: Architectural modernity in Egypt. During the past ten years, he has done much to shed light on this issue, first with his PhD thesis at New York University, which was translated into Arabic and came out as a book earlier this year from the National Centre for Translation under the title of Revolutionary Modernity: Architecture and Policies of Change in Egypt 1936-1967, and then in his 2020 book that came out from AUC Press in 2020 under the title of Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide.

The exhibition relates very much to his Guide. “I think it is very important to discuss modern architecture in this part of the world as part of approaching the history of the city and also as part of showcasing a profile of the city that is often marginalised by the colonial narrative that seems to restrict the glamour of our architecture either to historic buildings or to buildings that were constructed with European inspiration at the turn of the century 20th century,” he said.

Following the trail of architectural modernism ElShahed is working to de-abstract the past and decolonise the narrative of Cairo

Speaking to Al-Ahram Weekly from New York where he is currently living, ElShahed said that his two books constitute part of a contribution to the cause of documenting the history of the city. This was “a continuous project that requires a lot of work,” he added.

ElShahed studied architecture and the history of architecture in several schools in New York, which he moved to as a 15-year-old with a family that had previously lived and worked in Kuwait almost since his birth in 1981. They had to exit the country upon the Iraqi invasion in August 1990 to go back temporarily to their hometown of Alexandria.

In 2010, ElShahed arrived in Cairo to work on his PhD. He first lived in a downtown apartment, but only for a short while before he moved to the other side of Tahrir Square to live in Garden City, “a neighbourhood that has certainly undergone so much, but that still has a hidden charm for those with the eyes to see it.”

It did not take long for ElShahed’s life in Cairo and that of the entire nation to go through the most unexpected moments with the 25 January Revolution in 2011. The excitement of the Revolution contributed to the fascination that ElShahed had towards a city that was slowly but surely becoming his.

“For me, Cairo was always this ‘other’ fascinating city that I would come to as a young boy with my father for the holidays, unlike Alexandria that I have a very layered and complex relation with. I guess this has to do with my being Alexandrian — so for me Cairo was what Alexandria is for some Cairenes: the other city that is also intriguing and inspiring.”

This explains the admiration that ElShahed has for Youssef Chahine’s short film Cairo as seen by Youssef Chahine, one that shows the beauty and the agonies of the capital in a soft but affirmative way.

“There is so much in the cinema and literature to tell us about Cairo and from so many perspectives that vary from that offered by the novels of Naguib Mahfouz,” ElShahed said. “I think this is one of the best stories told of Cairo — perhaps because it is told by someone who is essentially Alexandrian,” he said, referring to Chahine’s film.

“It is important to say that my take on Cairo would be different from that of someone brought up in the city. Obviously, everyone’s take on any city relates very much to who this person is and why he would be in a particular place at a particular time,” ElShahed said.

“This is why I think it would be very presumptuous of anyone to think that what they see when they look at a particular photograph is necessarily what others see when they look at the same picture, or for that matter at the same building or the same street,” he added.

“Ultimately, the story we tell of a city is always shaded with our own story. A city is not abstract, and one should never try to separate the city from its people.”

“I guess that when someone like myself ends up moving often from one city to another, they end up being in a place where their relation with a city, intimate as it might be, does not deny them the ability to look at it from afar — sort of a zoom-in and zoom-out exercise that gets one to notice better perhaps,” he said.

RESEARCH: During his early years in Cairo, both for the purposes of his PhD and for the curiosity that he had towards the city, ElShahed was driven to walk endlessly around to assemble part of his own narrative.

For him, the most attractive points were the buildings built to a modern design.

In Cairo, ElShahed found “some really beautiful buildings of modern design” that he thought offered the antithesis to a narrative that argued that architectural aesthetics in Cairo were compromised after the 1952 Revolution.

The alternative thesis that ElShahed wanted to argue for was that modernity in architecture, embraced earlier than 1952, was in a sense an act meant to defy the architectural imprint of colonialism.

ElShahed argues that graduates of the Architecture Faculty at Cairo University were already embracing modernity before 1952. This trend was then “compatible with the call of the regime that came in the wake of 1952, as it obviously aimed to modernise,” adding that “it is important to resist a class monopoly of the story of the architecture of the city during the 20th century.”

When ElShahed was approached by the publisher of his Guide to Cairo, the initial idea was to do a book on the Downtown and Zamalek districts. His proposal, however, was to pursue another path and to go beyond the established narrative.

His objective was not just about questioning a long-standing thesis, however. It was also an attempt to offer an alternative view of Cairo, both in the architectural and urban meanings. “The 226 pictures that I ended up including in the book tell only part of the story of architectural modernity in the city. A lot more work needs to be done on this front,” he said.

It was this wish to share views and perspectives on the city that prompted ElShahed in April 2011, at a moment when all narratives were being revisited and all givens seemed possible to challenge, to launch his Cairo Observer.

This is an online platform that offers a space for sharing and discussing architectural and urban accounts of Cairo and Egypt at large. The objective is simple and profound, as ElShahed describes it. It aims to stimulate public discourse about urbanism, cultural heritage, and architecture to help the people of the city and those who wish to study it to better understand the policies that shape the city and the challenges it is facing.

ElShahed argues that with every new account that one learns and every new picture of the city that one sees, the image of the city evolves. “The relation that one establishes with a city is always evolving, and by sharing what I have and what contributors offer, I think I am trying to help offer different perspectives,” ElShahed said.

“We always have an illusion about having one stable and unchallenged take on the city, but this is not true,” he added.

CHANGES: At a moment when the city is going through many changes, the Cairo Observer, which started as a kind of a blog before evolving into a popular Instagram page, is there to offer a space for discussion and to help connect readers with the activism and grassroots action that engages with the urban reality of the city.

During the past ten years and no matter the changes that the city has been going through, including the dramatic changes that have hit Heliopolis, the suburb that ElShahed eventually ended up residing in for the best part of his ten-year stay in Cairo, he has not allowed this platform to assume a monopoly over the story of Cairo from any particular perspective.

He remains committed to telling the story from diverse perspectives. He believes that any monopoly on the narratives of the city, whether class or intellectually based, is as destructive to documenting the memory of the city as the waste of architectural gems, established trees, or old documents.

At a time when Egyptian universities still have to make space for departments that cater for specialists in architectural history, ElShahed hopes that initiatives like the Cairo Observer can perhaps fill a vacuum.

“One of the things that testifies to the size of this vacuum is the challenge that translators face when working on turning English texts on architectural history into Arabic because often the concepts need to be introduced where they have not previously been known,” ElShahed said.

“I think this is why translators like Amir Zaki, who worked on translating my PhD thesis for the National Centre for Translation, are actually helping a lot with making knowledge on architectural history accessible to as many readers as possible,” he added.

Earlier this summer, the Supreme Council for Culture announced that Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide had won the 2021 State Encouragement Award in the category of Architectural and Urban Publishing.

For ElShahed this was a very pleasant surprise — not just because it was an acknowledgement of the work he has been doing on Cairo for the past ten years, but also because it would help to raise awareness of the need to pay more attention to architectural history in general in Egypt.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 26 August, 2021 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

Short link: